The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

{

"authors": [

"Mark Baldassare"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Democratic Innovation"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "CC",

"programs": [

"Carnegie California"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Climate Change",

"Education"

]

}

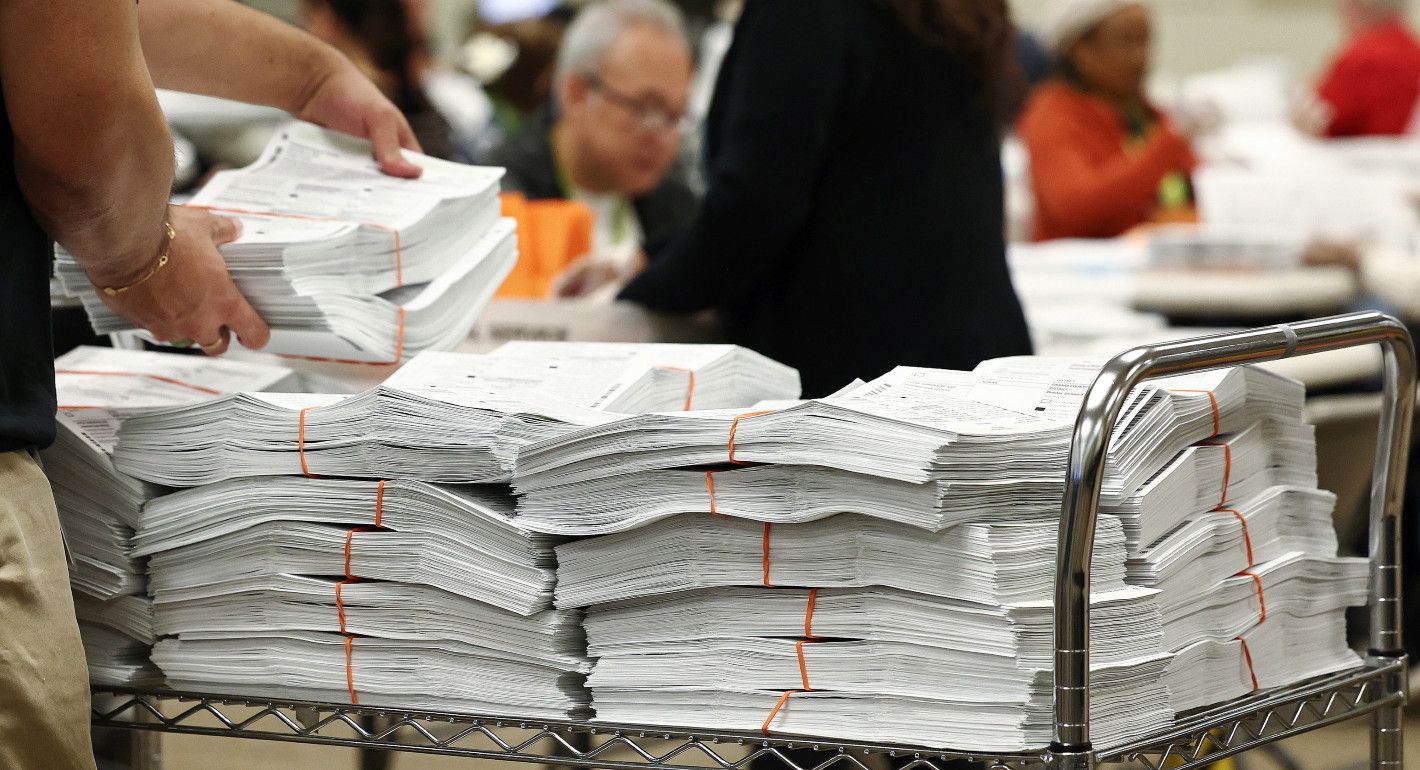

Election workers process ballots on November 12 in Santa Ana, California. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

The state’s voters defied the narrative of a tectonic political shift.

Earlier this month, Donald Trump was elected president with nearly half of the popular vote and a wide margin in the Electoral College. National exit polls confirmed that many voters were in the mood for change in federal leadership. Yet the voters in forty-one states—weighing in on 146 ballot propositions on a grab bag of policy issues—offered contradictory evidence about the direction that they want the political winds to blow. For example, majorities of voters in seven of ten states passed ballot measures to protect abortion rights, including Arizona and Nevada, which flipped from Democrat to Republican in the presidential contest.

California voters also defied the current narrative of a tectonic political shift in the U.S. electorate. The most populous state kept its blue reputation fully intact: Large majorities favored Democrats Kamala Harris for president and Adam Schiff for U.S. Senate, and Democratic candidates won in forty-one of the fifty-two House races. The state’s direct democracy system remained popular with voters, but they appeared to view it as less than perfect for policymaking. They seemed to be following the “canoe theory of politics” espoused by former governor Jerry Brown: paddle to the left, then paddle to the right. The five legislative measures and five citizens’ initiatives on the ballot—and reasons for their successes and failures—offer a window into direct democracy and its potential in the future U.S. election landscape.

The California legislature placed two bond measures and three state constitutional amendments on the November ballot for majority voter approval. Three of the five passed.

Two large state bonds that voters passed are highly consequential. Proposition 2 (59 percent yes) provides $10 billion for education facilities, and Proposition 4 (60 percent yes) provides $10 billion for climate programs. The pre-election polling found majority support for the state bonds even while most California voters have fiscally conservative leanings. Supporters inside and outside of state government joined forces in raising voters’ awareness about these legislative bond measures for schools and climate change preparedness.

Proposition 3 (63 percent yes) amends the state constitution wording on marriage equality by removing the mention of a ban on same-sex marriage. Voters passed this restriction by a narrow margin in 2008, and it was later ruled unconstitutional by the courts. Today, most Californians approve of same-sex marriage, and pre-election polling showed strong support for this state ballot measure. The opponents did not actively campaign against a measure that keeps the status quo of marriage equality in California today.

Proposition 5 (55 percent no) would have amended the state constitution by lowering the vote threshold from two-thirds to 55 percent to pass local bonds and taxes for affordable housing and public infrastructure. This amendment would have revised Proposition 13, which was passed in 1978. Recent polling finds that the Proposition 13 supermajority requirement remains popular. The legislature and its supporters did not actively campaign to explain to voters how this threshold change would provide more affordable housing.

Proposition 6 (53 percent no) would have amended the state constitution by removing a provision allowing “involuntary servitude for incarcerated persons.” Legislators’ intent was to end the exception of slavery in jails and prisons, but “slavery” was not mentioned in the ballot wording. One legislator was listed as a supporter, and the measure had no active campaign. Next door, Nevadans (61 percent yes) passed a ballot measure that removes “slavery and involuntary servitude as a criminal punishment” from their state constitution.

Ten citizens’ initiatives and two referenda had collected the signatures needed to qualify for the ballot. But four initiatives and two referenda were withdrawn by proponents, and one initiative was removed by the courts, leaving five initiatives on the November ballot. Three of the five passed.

Proposition 32 (51 percent no) would have raised the minimum wage. Oddly, no supporters were listed on the ballot, and proponents did not campaign. Most Californians say they favor an increase in the current minimum wage, but many also worry about the cost of living, and the initiative’s opponents emphasized that wage increases will lead to higher prices.

Proposition 33 (60 percent no) would have expanded local rent controls. Similar initiatives were widely rejected by voters in 2018 and 2020. Still, most Californians favor expanding local governments’ authority to enact rent controls. But the proponents had no answer when opponents raised concerns that this initiative would have negative impacts on affordable housing.

Proposition 34 (51 percent yes) will restrict how health care providers spend revenue earned from a federal discount prescription drug program. This spending restriction specifically applies to Proposition 33’s sponsor, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, and its passage will hamstring the organization’s efforts to qualify and campaign for citizens’ initiatives. The business groups that opposed Proposition 33 ran a parallel campaign that led to Proposition 34 passing.

Proposition 35 (68 percent yes) makes permanent the tax on managed health insurance plans and requires that it only be spent on certain Medi-Cal programs. The initiative’s proponents had an active campaign, and there were no opponents listed on the ballot label. The proposition’s passage reflects the voters’ priorities for state spending on health services in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Proposition 36 (68 percent yes) allows increased sentences for certain crimes. This changes Proposition 47, which voters passed in 2014. In recent polling, many Californians said that local property crime was a rising problem in their communities. Pre-election polling found this initiative had the most interest and support of the ten state propositions, and proponents included local government officials and bipartisan state leaders. The supporters tapped into concerns about crime that surfaced in Northern and Southern California and across the country. The governor and legislature were unable to agree on a competing legislative ballot measure and, while stating opposition to Proposition 36, did not campaign against it.

Most Californians went into the 2024 election believing that state ballot initiatives bring up important policy issues, including education, climate, and health care. However, most voters in pre-election polling said there are too many propositions and that understanding what happens if they pass can be challenging. This may explain why many reliably blue voters said no to seemingly liberal ballot measures, such as increasing affordable housing, raising minimum wages, and removing involuntary servitude from the state constitution. Californians’ ideas for improving direct democracy focus on more information to make policy choices. Half of residents say the state’s voter information guide is very useful. Voters favor adding town halls, televised debates, and an independent citizen’s initiative commission into their mix of trusted sources.

In this election cycle, state ballot measures were prevalent and made impacts in California and forty other states. State direct democracy may be on the rise in a changing federal policy landscape. Voters can use initiatives to express the economic frustrations and pessimism, while legislators turn to constitutional amendments and new laws to protect their states’ policies. California and about half of other states have initiatives and referendums, and most legislatures can ask voters to make policy changes. The voters’ wish list for more information should be greenlit for the 2026 election by state legislatures, election officials, and civic groups aiming to improve the election process. Voters’ positive experiences with state ballot measures can help bolster trust and confidence in U.S. democracy.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

The EU lacks leadership and strategic planning in the South Caucasus, while the United States is leading the charge. To secure its geopolitical interests, Brussels must invest in new connectivity for the region.

Zaur Shiriyev

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar