It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella

Source: Getty

Turkey’s approach to regional tensions and other looming security challenges is shaped by its deep commitment to building stability and cooperation in its neighborhood and the wider Euro-Atlantic community.

Turkey’s approach to regional tensions and other looming security challenges is shaped by its national strategy of “zero problems” and deep commitment to building stability and cooperation in its neighborhood and the wider Euro-Atlantic community. After five decades defending NATO’s southern flank and serving as a Western bulwark against turmoil in the Middle East, the Turks have endeavored to serve as a bridge between old adversaries and longtime allies. Given developments in Russia, the Caucasus, the Middle East, and North Africa over the past few years, this goal has required a difficult balancing act. This article examines the Turkish government’s approach to dealing with regional conflicts, missile defense, conventional force limits, and transnational terrorism.

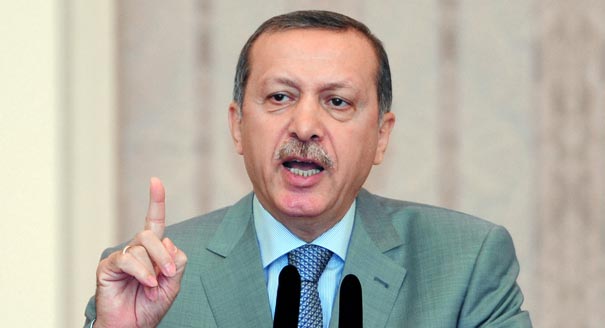

“Zero problems” with neighbors is a challenging national goal, particularly for a country nestled somewhat uncomfortably between the European Union and two of the world’s most volatile regions: the Middle East and the Caucasus. Yet that is one of the key principles animating the foreign policy of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) government since it took office in 2002.

This strategy has been heavily influenced by the worldview of Ahmet Davutoglu, the prime minister’s longtime adviser and current foreign minister, who has advocated leveraging Turkey’s geostrategic location in the center of Eurasia, as well as its historical Ottoman ties and Muslim affinities, to achieve “strategic depth” in its neighborhood and wider global influence. To achieve this end, the AKP government has pursued active regional diplomacy and economic engagement to avoid conflicts with all Turkey’s neighbors.

Expanding trade, investment, and tourism, cooperation on security issues (particularly on countering terrorism and Black Sea security), as well as a close personal relationship between Prime Ministers Vladimir Putin and Erdogan has led to deepening bilateral ties with Russia. The measured Turkish response to the August 2008 conflict in Georgia was a visible manifestation of Turkey’s effort to play a balancing role in relations between NATO and Russia and to promote stability in the Caucasus.

Davutoglu and other AKP strategists also envision that through deepening economic ties and efforts to support peaceful settlement of regional disputes, Turkey can serve as an honest broker between Muslim states in the Middle East and the West. They also believe that deeper Turkish economic and political engagement with Iran could foster a historic reconciliation between Sunni and Shi’i Muslim communities.

Erdogan and Davutoglu have seen the concept of strategic depth as a way to lessen Turkey’s historic dependence on the United States and Europe. While opposition critics, especially from the more nationalist strain of Turkish politics, argue that the policy is naïve and unsustainable in the face of growing regional turmoil, Turkish elites and the attentive public support the broad contours of this strategy to ensure that the country’s remarkable prosperity continues for another decade. Most Turks no longer see NATO as the primary foundation of their country’s security, but they still value the collective security guarantee and linkage to the United States and transatlantic security community that the Alliance brings. These somewhat conflicting goals have led to some difficult balancing of Turkey’s relations with Europe, the United States, Russia, and Iran.

Turkey has a strong interest in preserving stability in the Caucasus and Central Asia to allow for expansion of regional trade and infrastructure that will facilitate its development as a major hub for energy transit and other commerce. While economic and energy cooperation with Russia has deepened, mutual suspicions persist with respect to a number of regional political and security issues. Russia retains the dominant position due to historical, economic, and security ties. Turkish leaders remain wary of Moscow’s aspiration to create an exclusive sphere of influence in the region and to control energy flows from the Caspian Basin. Turkish efforts to play a larger role in the region, including its post-Georgia War Caucasus Stability and Cooperation Platform, have not gained traction, and little progress has been made toward normalization of relations with Armenia.

Turkish leaders have pursued several initiatives to engage Russia and other states in the Black Sea area in economic and security cooperation with limited success. In the early 1990s, Turkey proposed wide-ranging economic cooperation among countries in the region that has evolved into the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC). In 2001, Turkey led efforts to establish BLACKSEAFOR, a naval task group designed to foster regional stability, cooperation, and mutual understanding among Black Sea littoral states. Naval vessels from Turkey, Bulgaria, Ukraine, the Russian Federation, Georgia, and Romania have participated in search and rescue operations, as well as humanitarian assistance, peace support, mine counter measure, and environmental protection exercises over the past decade. In 2004, Turkey also initiated Black Sea Harmony, a maritime security operation designed to counter terrorism and illicit trafficking in the region. Black Sea Harmony was advanced by Turkey to complement and cooperate with NATO’s Operation Active Endeavor, which has a similar mission in the Mediteranean. Turkey did not want to raise tensions with Russia by supporting an expansion of NATO naval operations in the Black Sea. While the Turkish government sees these regional activities as contributing to broader Euro-Atlantic security, they proved of little value in dealing with the region’s biggest crisis—the 2008 Russian-Georgian war.

The steps required to achieve wider stability in the Caucasus and the Black Sea regions face many enduring political impediments. The international community should continue to encourage Turkey to normalize its relations with Armenia. As that process advances, Turkey would also like to play a larger role in the Minsk Group efforts to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Turkey’s cooperation with Russia on Black Sea security and other issues could be also be leveraged to advance the “reset” in U.S. and NATO relations with Russia.

Turkey’s approach to NATO missile defense plans and the U.S. European Phased-Adaptive Approach (EPAA) has reflected its “zero problems” strategy as applied to relations with Russia and Iran.

The Turkish government has supported NATO decisions to pursue cooperative development of theater and intermediate-range missile defenses with Russia and other Alliance partners since 2003. It welcomed the three joint NATO-Russia tactical missile defense command post simulation exercises, the computer simulation exercise, and the interoperability study conducted between 2004-2008 under the auspices of a special working group of the NATO-Russia Council—activities suspended following the Russian-Georgian war in August 2008.

Turkey supported the NATO Lisbon Summit decision to pursue a joint ballistic missile threat assessment and further missile defense cooperation with Russia, including resumption of theater missile defense exercises in 2012 and development of a joint analysis of the future framework for missile defense cooperation. Turkey will remain favorably disposed to this element of security cooperation with Moscow. It will be complicated by deepening bilateral economic and political engagement, but could build confidence with Russia.

The Turkish government does not assess Iran’s nuclear program and testing of long-range ballistic missiles as an imminent threat, but does see Iran’s prospective acquisition of nuclear weapons as inimical to its security. The Turks remain convinced that diplomatic and economic engagement offer the best route to convincing Tehran to forswear that quest. Thus, Turkey refused to allow the 2010 NATO Lisbon Summit documents to cite an emerging Iranian threat as justification for the Alliance’s development of a territorial missile defense system. While it may have placated Iran, this stance, coming six months after Ankara’s vote against further UN sanctions against Iran because of its nuclear efforts, further strained relations with many other allies. The Turkish government will continue to resist further steps by the P-5+1 and the UN to isolate Iran.

The desire to avoid antagonizing Iran along with other elements of its Middle East policy, have animated the Turkish government’s ambivalence about participation in the U.S. European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) system. In negotiations over the past two years, the Turks have yet to agree to be a basing state for the AN/TPY-2, a transportable X-band radar that would provide precise tracking information for SM-3 interceptor missiles deployed on U.S. Aegis-BMD capable ships in the Eastern Mediterranean during phase 1 of the program, and on land in Romania and Poland during phases 2 and 3. Turkish officials have cited concerns that the radar would leave parts of southeastern Turkey uncovered and made demands, which the United States has found unacceptable, concerning command and control arrangements and a ban on sharing information gathered by the radar with Israel. Underlying those official concerns, however, are the real ones: that participating in the system could lead to a deterioration of relations with Tehran and make Turkey more vulnerable to an Iranian attack if the threat emerges.

Ankara refused to make a decision on this issue before June 12, 2011, parliamentary elections. Washington has pressed Ankara for an answer since that time so that phase 1 of the EPAA can be fully operational by the end of 2011 as scheduled. The AKP government seems prepared to accept deployment of the radar, but will justify its decision as a purely defensive measure consistent with NATO obligations and long-standing national missile defense plans.

Turkey has not been among the NATO countries pushing for reductions in U.S. theater nuclear weapons that are deployed in several European countries, including Turkey, or for the initiation of the Alliance’s ongoing deterrence and defense posture review. While the Turks have reason to doubt the credibility of extended deterrence, having seen some of its NATO allies hesitate in providing appropriate conventional defense support during the Gulf and Iraq wars. Nevertheless, given the enduring dangers in their neighborhood, Turkish political leaders and the General Staff still value the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons in Turkey as a concrete linkage to the U.S. strategic nuclear deterrent and as a way to avoid making difficult decisions about whether to remain a non-nuclear-weapon state in the face of widening proliferation.

Turkey would certainly support development of a NATO dialogue on nuclear issues with Russia, as well as transparency and confidence-building measures, as called for by the NATO Group of Experts. They would also probably support some reductions in U.S. theater nuclear weapons in Europe in the context of a post-New START agreement that imposed limits on all nuclear weapons (including non-deployed strategic and theater weapons), so long as Turkey was not singled out as one of the few remaining basing countries for U.S. weapons. This would be inconsistent with the Turkish government’s zero problems policy, as well as its firm conviction that NATO member states should share defense and deterrence risks and responsibilities equally.

Moscow’s suspension of its compliance with the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty since December 2007 remains one of the few sources of tension in Turkish-Russian relations. Turkish officials still characterize CFE as “the cornerstone” of Europe’s security architecture and support revived negotiations and mutual concessions to salvage the Adapted CFE Treaty. The Turks see the CFE provisions, particularly the flank limits, which prohibit destabilizing concentrations of ground force equipment in northern and southern border regions, and the openness and inspection measures, as important restraints on Russian efforts to intimidate or intervene in the countries in the Caucasus. Ankara publicly disputed Moscow’s assertion that its suspension of CFE implementation was justified by the need to deal with a growing terrorist threat along its southwestern border. The Turks also lamented Moscow’s action in light of what it felt were vigorous NATO efforts to preserve the treaty and respond to Russian concerns.

Turkey has supported the “parallel actions package” advanced by NATO to restore the CFE regime and bring the Adapted CFE Treaty into force. They also endorse the NATO position that the Adapted CFE Treaty should not enter into force until Russia fulfills the Istanbul commitments with respect to the stationing of forces in Georgia and Moldova. In the face of the enduring CFE stalemate, the Turks advanced proposals to improve implementation of the OSCE Vienna Document and the Open Skies Treaty, as well as additional CSBMs. The Turkish government still holds that the legally-binding provisions of CFE cannot be replaced by politically binding commitments. However, such measures may be the best that can be achieved given Russia’s refusal to implement its Istanbul commitments and desire to remove the flank limits, as well as the unwillingness of NATO governments to effectively ratify the status quo in Georgia and Moldova as the price of retaining the CFE regime.

As part of their rapprochement, Turkey and Russia agreed several years ago to crack down on extremist groups operating in each other’s countries and to deepen their cooperation on combating terrorism. These measures are more than symbolic: The Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) had support networks in Russia and Chechen separatists had them in Turkey. This cooperation has expanded under the framework of the High-Level Cooperation Council (established in 2010 to manage deepening relations), and made it easier for the two governments to agree to reciprocal visa-free travel. This is another valuable element of building an integrated Euro-Atlantic security community that complements expanded NATO-Russia cooperation on combating terrorism.

Turkey’s approach to the key security challenges in the Euro-Atlantic area is to achieve peaceful relations with all of its neighbors, even as it recovers some measure of its Ottoman past as a regional leader and a more influential global player. Turkey seeks to achieve all this through dynamic regional engagement, including trade and economic and security cooperation. It’s “zero problems” strategy is consistent with the integral set of relationships endorsed by the OSCE and the Lisbon NATO-Russia Council Joint Statement for building a broader Euro-Atlantic security community. In the face of growing turmoil in the Middle East and North Africa and enduring “frozen conflicts” in the Caucasus, these laudable goals will be difficult to achieve.

Stephen J. Flanagan is senior vice president and Henry A. Kissinger Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Before joining CSIS in 2007, he served as director of the Institute for National Strategic Studies and vice president for research at the National Defense University (NDU).

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

Leaning into a multispeed Europe that includes the UK is the way Europeans don’t get relegated to suffering what they must, while the mighty United States and China do what they want.

Rym Momtaz

Insisting on Zelensky’s resignation is not just a personal vendetta, but a clear signal that the Kremlin would like to send to all its neighbors: even if you manage to put up some resistance, you will ultimately pay the price—including on a personal level.

Vladislav Gorin

For Putin, upgrading Russia’s nuclear forces was a secondary goal. The main aim was to gain an advantage over the West, including by strengthening the nuclear threat on all fronts. That made growth in missile arsenals and a new arms race inevitable.

Maxim Starchak