If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

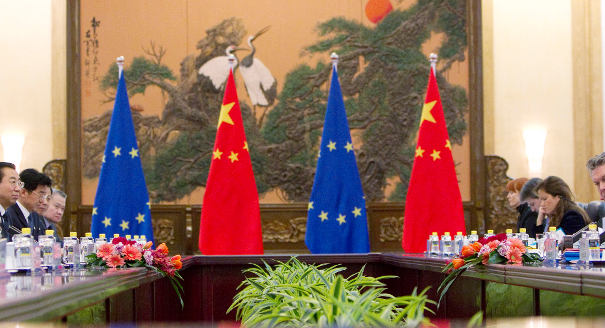

Source: Getty

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s upcoming Brussels visit signals a concerted Chinese effort to support the role of the EU as a major global actor in international affairs.

Chinese President Xi Jinping is expected to visit Brussels at the end of March 2014 for the first time since his 2012 election to the presidency. When the head of state of the world’s largest exporting country, China, is visiting the world’s biggest market, the EU, economists pay close attention. Political analysts are also looking to the trip for insight into the future of political relations between these two global actors—particularly now that European geopolitics have captured international attention with the crisis in Ukraine and anti-EU coalitions in Europe are undermining the future of the integration dream.

Xi has already made trips to Russia, Africa, the United States, and Latin America, which some have cited as evidence that the EU is considered a low priority in the new Chinese administration’s diplomacy. In reality, however, Xi’s relatively late visit to Brussels demonstrates the strength of China-EU relations. China has poured more of its diplomatic resources, time, and effort into work on some of the other relationships that it had neglected in previous years. In line with the Chinese saying that “friendly neighbors are more important than faraway relatives,” China has spent the past year looking to engage more with states along its periphery.

The Brussels visit will, however, be an important event for China’s relations with Europe. It will be the first time a Chinese head of state visits the city outside of a China-EU high-level summit, signaling a concerted Chinese effort to support the role of the EU as a major global actor in international affairs. It also indicates Beijing’s desire to deepen the China-EU relationship as the two actors enter the second decade of their Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

The two commercial behemoths of the Eurasian landmass have a wide range of areas in which deeper cooperation can produce benefits for both actors. Among these, emphasis should be placed on furthering China’s pressing economic reforms and reducing the EU’s economic struggles. Together, the two can also help build a more balanced multipolar world order.

In the aftermath of a China-EU summit that took place in Beijing in November 2013, the president of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, called Europe a partner in China’s development rather than just a simple trade partner. Indeed, the EU has been a sincere and trustworthy economic ally that has assisted China’s development. More recently, it has also helped China transition to a more environmentally friendly economic model by implementing joint initiatives on sustainable urbanization through city-to-city cooperation. The ambitious economic reform agenda that emerged from the Chinese Communist Party’s Third Plenum in November calls for even more daring economic collaboration between China and the EU.

While Xi’s visit to Europe should deepen the existing relationship, more initiatives should be undertaken that build on past cooperation in innovation, technology, and sustainable growth. As European Commissioner for Internal Market and Services Michel Barnier has put it, the future of the EU depends on advanced, high-tech manufacturing that demands an EU-wide industrial policy in accordance with World Trade Organization regulations and in consultation with important partners like China. This opportunity for cooperation must not go unnoticed.

China should reach out to Europe requesting a potential free trade agreement that will facilitate horizontal China-EU business partnerships, especially because the EU is potentially the only advanced economy that would partner with Beijing on such an endeavor. Neither Japan nor the United States would be willing to collaborate with China, Tokyo because of the Japanese prime minister’s nationalism and historical revisionism and Washington on the grounds of national security. However, more EU-China trade would contribute to global growth and thus benefit the U.S. and Japanese economies.

In its outreach efforts, Beijing should take steps to ensure that the EU does not feel economically threatened by China’s state-owned enterprises and industrial policy. It should look to work with Brussels to plan signature industrial projects that promote horizontal production partnerships, make use of China’s and the EU’s complimentary comparative advantages, and build joint ventures and advanced value chains. The very successful engagement of European universities in technology hubs in China could be a stepping-stone for such unprecedented partnership in twenty-first-century manufacturing.

A cohesive partnership between two major powers like China and the EU has to be supported by mutual understanding and support in times of crisis. China has not forgotten the developmental aid that the EU has provided. With the European project facing unprecedented problems, China should be ready to reciprocate.

Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) can assist depressed peripheral EU economies like Greece, Portugal, and Spain, helping reignite their productive potential, increase employment, and neutralize nationalist and protectionist political forces. To that end, a China-EU investment agreement would be welcome manna for Europe.

China is already investing in the EU, but Beijing provides less than 3 percent of all FDI going to the union. To date, China has invested more than $8 billion in Spanish bonds, raised its share in the International Monetary Fund to support the funding program for Greece, made multibillion-dollar investments in a Greek harbor and a Portuguese electricity operator, agreed to joint ventures for oil exploration with Spain’s Repsol, and established a fund of over $40 billion in EU-specific capital in the China Investment Corporation to help Chinese companies invest in Europe.

In addition, as China has surpassed the United States and Germany in the number of outbound tourists, the EU and China could engage in a bilateral agreement that further facilitates Chinese tourism in Europe. They could promote an easier visa regime and establish more direct flights between China and EU cities.

In the monetary realm, China could discuss expanding on its existing currency swap agreement with the European Central Bank, which would show confidence in the euro as a pillar of global macroeconomic stability. Furthermore, a road map to set up an official renminbi offshore trading center in Europe would be a great signal of China’s trust in the euro, one that the markets would certainly notice.

Finally, it is crucial for the EU to reach out to China with a proposal on how exactly Beijing can constructively support the European economy. While Germany is the most successful EU state in terms of economic engagement with China, there is a significant amount of untapped potential in southern and eastern European countries that the European Commission and Chinese authorities could work together to realize. While China respects the cohesion and policy role of the European Commission, it is also ready to work with individual states when necessary.

In a June 2013 summit between the U.S. president and the Chinese president, Xi promoted the concept of “a new type of great-power relations,” signaling that he believes it is possible for China and the United States to avoid the so-called Thucydides trap—the theory that, as Beijing’s power increases, U.S. anxiety about China’s rise will make it inevitable that security competition will increase.

China has been pressed to clarify the characteristics of this new model and to explain how it will be operationalized. The hallmarks of this "new type of great-power relations," in Xi's own words, are "the principles of non-conflict, non-confrontation, mutual respect and win-win cooperaiton." And, this model does not only refer to China-U.S. relaitons. It also applies to the relationships between China and other power, such as Russia and the EU, as well as to partnerships between any two major powers.

The equal relationship and benign diplomatic interaction between Beijing and Brussels and the modus operandi of the China-EU comprehensive partnership could offer some real and pragmatic examples for China-U.S. relations. For example, collaboration between China and the EU in sending peacekeepers to Mali, Chinese support of EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Catherine Ashton in nuclear negotiations with Iran, and antipiracy cooperation between Beijing and Brussels should serve as a valuable road map for great-power interaction between China and the United States.

Beyond bilateral relations, the EU approach to world affairs could serve as an attractive diplomatic model for China because of the union’s influential cultural and normative power and the fact that Brussels uses a less coercive form of diplomacy than the United States. Beijing welcomes Europe’s diplomatic accomplishments and its support for dialogue. These attributes of the EU could help promote some of China’s priorities, including multipolarity and peaceful dispute resolution, which have been core principles of the country’s foreign policy for nearly two decades.

In a recent statement, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi acknowledged the EU’s position as a major power, civilization, and market in the world and noted that China-EU cooperation can lead to a more balanced world. However, the two sides are not operating together to reform the international system because they have no final design on what they want the system to be. They are instead incrementally fostering a relationship that will facilitate future cooperation in a decisionmaking process on global reform and multipolarity.

In 1914, might defined right in Europe and hegemonic clashes among European states pushed the world into industrialized death and massive warfare. The EU project has aimed to reverse that process. It was founded, as one expert put it, “on the rejection of power as a mode of regulating relations among nations.” Xi’s visit is a clear display of China’s support for the continuation of European integration and for the belief that Europe is a great power whose voice and conduct, in many cases, echo China’s vision of a multipolar and harmonious world.

But Xi’s visit can do more than just offer symbolic support for the European dream. It can also help accelerate the existing China-EU “marriage” in the economic dimension and further the political dimension of the China-EU partnership. Closer cooperation in these areas will deliver great benefits to both Beijing and Brussels.

This article was published as part of the Window into China series

Shi Zhiqin

Former Resident Scholar, Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy

Shi Zhiqin was a resident scholar at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center until June 2020.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

If the regime in Tehran survives, it could be obliged to hand Moscow significant political influence in exchange for supplies of weapons and humanitarian aid.

Nikita Smagin

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev