Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

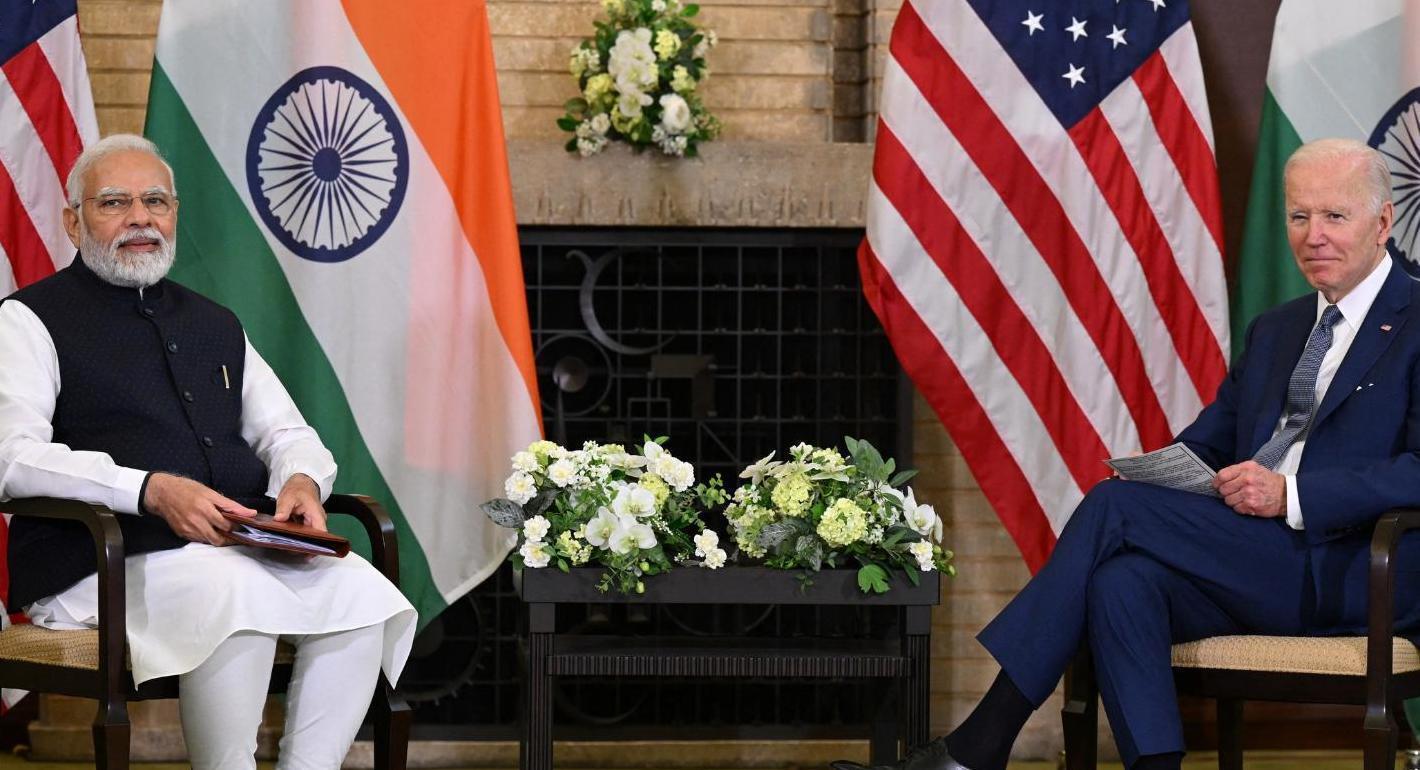

Source: Getty

With Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s upcoming visit to the United States, India-U.S. relations merit a closer look. This article outlines the likely next steps for continuing successful bilateral relations between the two countries.

The year 2000 marked the beginning of a new phase of sustained consolidation of relations between India and the United States. Alongside the growing convergence of interests, each successive U.S. president and Indian prime minister has brought their own vision and imprint to bear on the evolution of the India-U.S. relationship.

Former president Bill Clinton pioneered this phase. In the wake of the nuclear tests conducted by India in May 1998 and the subsequent, strident criticism and sanctions from the United States, he tasked then deputy secretary of state Strobe Talbott with starting a series of deep-dive discussions with his Indian counterpart, Jaswant Singh, who was mandated by the prime minister (and who later became India’s foreign, defense, and finance minister at various times). These discussions aimed to understand strategic compulsions and explore convergence. In addition to these efforts, Clinton’s visit to India in March 2000 set the countries on a new path. Speaking at the Indian Parliament on March 22, Clinton evoked the idea of “two nations conceived in liberty, each finding strength in its diversity, each seeing in the other a reflection of its own aspiration for a more humane and just world.” He added: “We welcome India’s leadership in the region and the world . . . we want to take our partnership to a new level, to advance our common values and interests.” 1

Following Clinton’s example, former president George W. Bush tasked Condoleezza Rice with focusing on developing relations with India even before he formally launched his presidential campaign in 1999. This is attributed, inter alia, to his experience with Indian-origin professionals in Texas, including their support for his political campaigns. Speaking at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library on November 19, 1999, Bush said, “Often overlooked in our strategic calculations is that great land that rests at the south of Eurasia. This coming century will see democratic India’s arrival as a force in the world.”2 After becoming president, he asked his administration to find ways to deepen the U.S.-India partnership. This led to the internal conclusion that the United States needed to remove existing civilian nuclear technology restrictions on India to enable higher-level technology releases for strengthening economic and investment links and a robust defense partnership. These efforts culminated in the pathbreaking Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, signed in 2008.3 Discussions to finalize the agreement started in 2005, but bureaucratic and nonproliferation-related concerns and advocacy in the U.S. Congress and policy community repeatedly caused roadblocks. It is acknowledged that it often took Bush’s personal intervention and push for agreed outcomes to keep the process moving. During his final meeting with Bush on September 25, 2008, visiting Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh said that “the people of India deeply love you” (at a time when Bush had become extremely unpopular in the United States on account of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the failure and losses from that effort). Singh added, “When history is written, I think it will be recorded that President George W. Bush played a historic role in bringing our two democracies closer to each other.” 4

As a senator, Barack Obama had moved amendments that would have effectively derailed the Civil Nuclear Agreement during its Senate consideration, but he eventually voted for its passage. In an interview with TIME magazine on October 23, 2008, the presidential candidate Obama spoke of appointing a special envoy to deal with the Kashmir issue, 5 (contrary to India’s firm opposition to any third-party role). However, as president, he refused the persistent attempts of his special envoy, Richard Holbrooke, to add India to his Afghanistan-Pakistan portfolio. Obama invited Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh as the first state visitor of his administration in November 2009,6 and he declared support for India’s permanent membership on the UN Security Council during his own visit to India in November 2010. (It was the president who reportedly took the final call on this, given the divided opinion among his staff.) Obama then invited the newly elected Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to visit the United States in September 2014, despite earlier differences on the matter of granting him a visa,7 and followed soon thereafter by visiting India on January 25–26, 2015, as Special Guest on Republic Day, a first for any U.S. president. To enable a visit on this date, the date of the president’s State of the Union address to the U.S. Congress was reportedly advanced,8 another indication of Obama’s personal commitment to advancing India-U.S. relations and assessing potential gains for U.S. interests. His administration also declared India a Major Defense Partner,9 enabling higher-level technology releases.

Obama’s successor to the presidency, Donald Trump, was considered a maverick, someone from outside the recognized political establishment. However, he recorded a campaign video aimed at the Indian-origin community, articulating “ab ki bar Trump sarkar” (roughly, this translates to “this time, a Trump administration”)10, echoing a similar slogan used during Modi’s 2014 election campaign. Trump addressed a campaign rally of Indian Americans in New Jersey in October 2016. As president, he joined the Indian prime minister at a 50,000-person-strong rally in Houston in September 201911 and addressed a welcome crowd of 100,000 at Motera Stadium in Ahmedabad in February 2020.12 He placed India at Strategic Trade Authorization Level 1 for technology releases, at the same level as the United States’ closest allies. His Indo-Pacific-focused reactivation of the Quad in 2017, with official and ministerial-level meetings, enhanced the willingness in both countries to deepen the bilateral partnership in various dimensions. His domestic-politics-driven tariff and trade measures against India, including the termination of benefits under the General System of Preferences, did cause unhappiness, but he sustained an overall positive trajectory, including in his relationship with the Indian prime minister.

Similarly, former Indian prime ministers, including Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh, put their weight behind advancing India-U.S. relations. Vajpayee spoke of India and the United States being “natural allies.”13 Singh staked the survival of his government in 2008 on getting the Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement passed through Parliament.14

With the above background in place, it would be instructive to assess how Modi and Biden, in different capacities, have so far impacted the evolution of the bilateral relationship and the opportunity that this provides for the future.

Modi is now visiting the United States from June 21–23, 2023, as only the third state visitor of the Biden administration, following French President Emmanuel Macron in December 2022 and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol in April 2023.15 Modi will be the third Indian leader ever invited to the United States on a visit of this level of protocol, after president S. Radhakrishnan in 1963 and prime minister Manmohan Singh in 2009.16

He will also be addressing a joint session of the U.S. Congress on June 22 for the second time (after his first address in 2016). 17

Modi has visited the United States on numerous occasions since September 2014 for bilateral and multilateral meetings. Many of these have been visits to U.S. cities with a significant Indian-origin diaspora and business presence. A completely new element has been the gathering of huge crowds for Modi’s addresses in major cities. For example, the 2014 event in New York City drew 19,000 people,18 the 2015 event in San Jose, California, drew 18,500 people,19 and the 2019 event in Houston, Texas, drew 50,000 people.20 These events have been attended by several U.S. congresspeople and local elected leaders. Trump spoke at the Houston event and was present throughout, walking around the stadium while holding hands with the Indian prime minister at the end. These events showcased ardent support for Modi in sections of the Indian-origin community and were of interest to U.S. leaders seeking funding, support, and votes for their own campaigns. Modi has also made a determined effort to build and project endearing personal relationships with his various counterparts, including the reticent Obama, the awkward Trump, and now the politically savvy Biden. This is similar to his efforts with leaders of some other countries, including Australia, France, Israel, Japan, the UAE, and others.

In September 2014, Modi and Obama issued a joint statement21 and vision statement for the U.S.-India Strategic Partnership with the message “chalein saath saath, forward together we go.” 22 During Obama’s visit in January 2015, the two sides issued the Delhi Declaration of Friendship23 and adopted the Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia-Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region.24 This was the first time the two countries had jointly articulated the challenges in the region and was a forebearer of subsequent work in the Quad and on approaches to the Indo-Pacific strategic construct.

In September 2015, Modi visited the United States again, this time focusing more on the UN General Assembly. He held a bilateral meeting with Obama in New York and interacted with the Indian community as well as prominent figures from business, the media, and academia. The following year, he made an official working visit in June. During the visit, he held bilateral discussions with Obama and addressed a joint session of the U.S. Congress,25 becoming the sixth Indian prime minister to do so.26 There, he spoke of overcoming the “hesitations of history” in relations with the United States.27

Trump and Modi had spoken and met on multiple occasions since Trump’s election in November 2016. In 2017, a hotline was established between the Prime Minister’s Office and the U.S. White House,28 further enhancing communication between the two governments.

The two countries were able to finalize the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) in 2016, the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) in 2018, and the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) in 2020, all of which had stalled for years. These agreements have enhanced defense ties, intelligence sharing, and interoperability between the armed forces of both countries. Such ties were of use when India faced incursions from China along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh in 2020.

Collaboration in defense and counterterrorism has also witnessed significant progress, with bilateral joint military exercises, including Yudh Abhyas, Vajra Prahar, Red Flag, and Cope India. The two countries have also been a part of the Malabar exercises with Japan, which now include Australia as well.

Biden’s engagement with India began long before he became president.

In 1998, when India conducted its nuclear tests, then senator Biden recognized the significance and stature of a nation like India and emphasized that it could not be isolated forever.

In 2001, as the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he penned a letter to then president George W. Bush urging his administration to lift sanctions imposed on India, arguing: “The economic sanctions against India serve to stigmatize rather than stabilize, if the sanctions are removed, India will respond with reciprocal acts of goodwill in non-proliferation and other arenas.” 29

In 2006, he said, “My dream is that in 2020 the two closest nations in the world will be India and the United States. If that occurs, the world will be safer.”30

Biden played a significant role in the U.S. Senate’s approval of the historic nuclear deal with India in 2008. “It’s more than just a nuke deal. It is part of the dramatic and positive departure in our relations,”31 he said upon approval. In 2015, at an event commemorating the agreement, vice president Joe Biden said, “Ten years ago, I had the honor of—because of my position as chairman of the Committee—of leading the U.S. Senate in an effort to ratify the U.S.-India civilian nuclear agreement, and it helped, in my view, to remove the single largest irritant between two of the world’s greatest democracies.”32

He consistently advocated for stronger counterterrorism cooperation between the two countries. He also condemned terrorist attacks targeting India and expressed solidarity with the Indian government.

In 2013, speaking at the Bombay Stock Exchange, he emphasized the importance of expanding economic ties between the two countries. He said, “We Americans are confident that India will continue to rise because we believe you will take the additional steps necessary to spur further growth and enhance your economic influence around the world, and in the process lift the whole world. We want to be your partner in that venture, in lifting the economy of the world.”33 He reiterated Obama’s comment that India-U.S. relations would be one of the defining partnerships of the twenty-first century.

Biden also consistently highlighted the shared values between the United States and India, such as democracy, diversity, and respect for human rights. At times, his doing so was also seen as a veiled criticism of some of the continuing challenges in India as perceived in the United States. In 2019, following the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian constitution, he called for the “restoration of rights for the people of Kashmir” and committed to raising human rights issues with the Indian government.34

Similarly, during their joint campaign, Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris stressed the principles of democracy, equality, freedom of expression and religion, and the strength derived from diversity, highlighting the shared values that bind the two nations together. “We will meet every challenge together as we strengthen both democracies—fair and free elections, equality under the law, freedom of expression and religion, and the boundless strength both nations draw from our diversity. These core principles have endured throughout each nation’s histories and will continue to be the source of our strength in the future,”35 he stated.

Additionally, Biden highlighted his commitment to the Indian American community and pledged to strengthen India-U.S. relations. “We share a special bond that I’ve seen deepened over many years—as U.S. Senator and vice president, I’ve watched it deepen. Fifteen years ago, I was leading the efforts to approve the historic civil nuclear deal with India. I said if the United States and India became closer friends and partners, then the world will be a safer place,”36 he said.

Biden acknowledged the importance of regional stability and security in South Asia, affirming his dedication to working with India to address common security challenges and promoting peace in the region. “That’s why if elected President, I will continue what I have long called for: The U.S. and India will stand together against terrorism in all its forms and work together to promote a region of peace and stability where neither China nor any other country threatens its neighbours,”37 said Biden.

“Biden believes there can be no tolerance for terrorism in South Asia – cross-border or otherwise,”38 stated his campaign’s agenda for bilateral relations with India and the welfare of Indian Americans.

Recognizing India’s role in addressing climate change, Joe Biden expressed his intention to collaborate with the country on clean energy initiatives. He emphasized the need for both nations to work together in combating climate change, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and promoting global health.39 Biden vehemently objected to a comment made by Trump in a previously held presidential debate, where he referred to the air in India as “filthy.” Biden tweeted, “President Trump called India ‘filthy.’40 It’s not how you talk about friends and it’s not how you solve global challenges like climate change.” 41

Furthermore, Biden indicated that the United States, under his leadership, would lead international efforts to address global health challenges, potentially working in conjunction with India.42

Throughout his campaign, Biden acknowledged the Indian American community and the challenges they faced. He criticized the Trump administration’s crackdown on legal immigration, including restrictive actions on H-1B visas, and expressed concern at the rise in hate crimes impacting the community.43

During a South Asians for Biden event on August 15, 2020, Kamala Harris also emphasized her own South Asian heritage, expressing the importance of the Indian and American communities being connected through shared history and culture. She said, “To the people of India and to Indian Americans all across the United States. I want to wish you a happy Indian Independence Day. On August 15, 1947, men and women all over India rejoiced in the declaration of the independence of the country of India. Today, on August 15, 2020, I stand before you as the first candidate for Vice President of the United States of South Asian descent.” 44

Since becoming president in January 2021, Biden has taken several steps with a positive impact on the relationship. He elevated the Quad to summit-level meetings. A new grouping, I2U2 (which includes India, Israel, the UAE, and the United States), was launched, recognizing India’s interest in West Asia and its strong bilateral relations with the three other members. Following his joint statement with the Indian prime minister in July 2022, the two countries initiated a new collaboration framework for critical and emerging technologies.

Biden and Modi have met on several occasions and have also spoken on the telephone regularly. The first telephone conversations took place on November 17, 2020,45 soon after Biden’s victory, and on February 8, 2021,46 soon after he assumed office. They reaffirmed their commitment to working together against common challenges, such as COVID-19, global terrorism, and rebuilding the global economy. They also emphasized the significance of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

In the call on April 26, 2021,47 Biden assured Modi of the United States’ unwavering help in combating the COVID-19 outbreak. The United States pledged emergency aid, including oxygen-related supplies, vaccine materials, and more to assist India in addressing the challenges posed by the pandemic. India’s support through supplies to the United States in 2020 was also noted.

Biden and Modi emphasized the importance of economic cooperation and technology collaboration in their conversations on April 11, 2022,48 and February 14, 2023.49 The historic agreement between Air India and Boeing, involving the purchase of more than 200 American-made aircraft, was discussed in the February 2023 call. This agreement is expected to support over 1 million American jobs across forty-four states. Furthermore, both leaders acknowledged the significance of the strategic technology partnership, stressing the January 31, 2023, inaugural launch of the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET).

The U.S.-India Climate and Clean Energy Agenda 2030 Partnership

At the Leaders’ Summit on Climate in April 2021, the United States and India launched the U.S.-India Climate and Clean Energy Agenda 2030 Partnership.50 The partnership, which is led by Biden and Modi, focuses on making immediate progress during this critical decade for climate action. Both countries have ambitious targets to meet for climate and clean energy before 2030. The partnership aims to mobilize finance, accelerate clean energy deployment, scale innovative technologies, and build capacity to address climate-related risks. It operates through the Strategic Clean Energy Partnership51 and the Climate Action and Finance Mobilization Dialogue,52 building on existing processes. The cooperation aims to demonstrate how climate action can align with inclusive and resilient economic development, taking into account national circumstances and sustainable development priorities. The partnership exemplifies the commitment of both nations to achieve their climate and clean energy targets, a key area of focus between the two countries, while enhancing bilateral cooperation.

The U.S.-India Joint Leaders’ Statement: A Partnership for Global Good

During their first in-person meeting in Washington, DC, for the Quad Leaders’ Summit in September 2021,53 Modi and Biden reaffirmed their commitment to a free and inclusive Indo-Pacific region, discussing regional security, climate change, and a rules-based international order. They also issued a joint statement, titled “U.S.-India Joint Leaders’ Statement: A Partnership for Global Good,”54 emphasizing their commitment to expanding COVID-19 vaccine cooperation focusing on production, distribution, and administration. This joint effort showcased strong bilateral collaboration in fighting the pandemic. The two leaders also discussed enhancing defense cooperation, emphasizing the deepening of military ties, expanding defense trade and technology collaboration, and enhancing collaboration in maritime security and counterterrorism.

The U.S.-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology

Launched in January 2023 following guidance from a joint Biden-Modi statement in May 2022, the U.S.-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology represents a significant step toward fostering collaboration and innovation in the field of advanced technologies. The inaugural meeting discussed opportunities for future cooperation in the fields of artificial intelligence, quantum, cyber, 6G, semiconductors, space, defense, biotechnology, advanced materials, and rare earth processing technology.55 Various bilateral mechanisms set up for this purpose have met since to prepare potential outcomes for the state visit next week.

I2U2

Established in October 2021 at the foreign ministers’ meeting, the I2U2 aims to cooperate and invest in areas such as water, energy, transportation, space, health, and food security to address global challenges.56 Referring to the partnership between the four countries, then State Department spokesperson Ned Price said, “India is a massive consumer market. It is a massive producer of high-tech and highly sought-after goods as well. So, there are a number of areas where these countries can work together, whether its technology, trade, climate, COVID-19, and potentially even security as well.”57 Following a virtual summit of the I2U2 in July 2022, it was announced that the UAE would invest around $2 billion in food parks in India, aimed at food security for the Gulf, and in renewable energy projects.58 Future projects included enhancing infrastructure and connectivity in the Gulf countries.

The Interim National Security Strategic Guidance

Released by the Biden administration in March 2021, the document outlines the administration’s approach to global challenges, highlights its commitment to strengthening partnerships with key allies and partners, and asserts: “We will deepen our partnership with India.”59 Relatedly, the U.S. Department of State released its integrated country strategy for India in May 2022. Objective 4.2 in this document supports the Interim National Security Strategy, recognizing India’s “key role in multilateral and like-minded groupings focused on strategic challenges in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.”60 The integrated country strategy also highlights the importance of working with India to promote a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific, with an emphasis on regional stability, maritime security, and economic cooperation.

The Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States

Released in February 2022, the document recognizes India as a “like-minded partner and leader in South Asia and the Indian Ocean” and its role as a “net security provider” in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond. The administration also aims to “steadily advance [its] Major Defense Partnership with India” to enhance interoperability and increase the capability to counter common threats and maintain stability in the Indo-Pacific region.61

National Security Strategy

Released in October 2022, this strategy document highlights a community of nations, including India, that share the United States’ vision for an international order. The strategy emphasizes the necessity of addressing the shortcomings of the existing order and countering attempts by some states to promote a less open and free model. In pursuing a double track approach,62 the United States aims to cooperate with any country that is willing to work constructively on shared challenges while also deepening cooperation with democracies and like-minded states. In the document, the United States recognizes India’s significant role as the world’s largest democracy and a Major Defense Partner of the United States. India is seen as a key partner in advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific. The document outlines the commitment of the two countries to work together bilaterally and multilaterally to support their shared vision.

2022 National Defense Strategy

The National Defense Strategy, also released under the Biden administration in October 2022, highlights Washington’s strategic priorities and defense posture. It acknowledges the importance of partnerships and alliances in addressing global challenges. The United States, via this strategy, also aims to strengthen the security architecture in the Indo-Pacific region to maintain a free and open regional order and to deter the use of force in resolving disputes. This involves deepening cooperation within the Quad. Further, the United States aims to expand its Major Defense Partnership with India to enhance its ability to deter China’s “aggression” in the China-India border region and guarantee access to the Indian Ocean region.63

India did not join the United States in condemning or sanctioning Russia for its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. India has a legacy defense relationship with Russia, with nearly 60 percent of its defense inventory still of Russian origin. This is despite diversification efforts over the past two decades and increasing purchases from the United States, France, and Israel.64 In the past, the Soviet Union and then Russia provided political support to India when it was under pressure from the West and opposed U.S.-led sanctions against India following nuclear tests in 1998.

Following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the United States showed an understanding for India’s compulsions. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken recognized that India’s relations with Russia had developed when the United States was “not able to be a partner to India.” He further asserted that the “times have changed” and that the United States is now “able and willing to be a partner of choice with India across virtually every realm – commerce, technology, education, and security.”65 U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said that with India, the United States was “playing the long game.”66 India has also repeatedly expressed support for the “territorial integrity and sovereignty” of countries, an indirect criticism of Russia’s actions.67 In a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Modi said that “today’s era must not be of war,”68 a comment widely and approvingly noted globally.

The United States’ decision to withdraw from Afghanistan by the end of August 2021 caused anxiety in India with the inevitable prospect of a Taliban takeover and the attendant possibilities of Afghanistan- and Pakistan-based terrorism finding even more fertile soil and exploitation by Pakistani agencies for anti-India activity. There was, however, recognition of the fatigue in U.S. society and body politic from extended overseas military engagements. India also moved deftly amid the flux to establish a liaison presence in Kabul to continue with its humanitarian assistance. There have been reports of differences between the Taliban and the Pakistani establishment, including on the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan.69 There have also been no reports so far of any major Afghanistan-based terrorism directed against India.

There was also unease in India over the United States’ decision to authorize a $450 million sustainment package with Pakistan for F-16s, which have been used against India.70 From its perspective, the United States wants to sustain some ability to communicate effectively with the Pakistani leadership, particularly in the army. Additionally, from a strategic and commercial standpoint, the United States wants the ability to sustain the efficacy of the platforms it has supplied in the past. This is clearly an area where the two countries will disagree, but there is sufficient dynamic in the overall relationship to deal with this hurdle.

Modi’s state visit to Washington will also be a celebration of the breadth of the India-U.S. relationship. The Indian diaspora in the United States is now estimated to be more than 4 million, the largest single-country presence of persons of Indian origin. Indian Americans occupy key positions in the administration, Congress, and business. Trade between the two countries reached $191 billion in 2021–2022, and the United States has become India’s largest trading partner.71 Both countries have invested around $40 billion in the other, with Indian companies now having a presence in all fifty U.S. states. Defense trade and technology partnerships are growing, with both nations doing more military exercises with each other, with increasing complexity and building toward interoperability. There are more than 200,000 Indian students in American universities,72 with the potential for developing new networks of commercial relationships in the future.

Both leaders will, no doubt, also use this visit to send a message to stakeholders in the relationship and globally. There will be a recognition of shared interests, including in the Indo-Pacific, and the utility of shared values.73 There will be support for democracy, human rights, and inclusiveness. But most of all, there will be an acknowledgment of the growing convergence of interests, despite some differences, amid the current global flux and challenges in the Indo-Pacific. In specific terms, if a decision on cooperation in semiconductors is possible and the GE proposal for the transfer of technology and production of jet engines in India is approved,74 there will be a major boost in business confidence and technology partnerships.

Of late, there have been varying assessments of the depth of India-U.S. relations and their prognosis. It has been variously suggested that the United States has made a bad bet75 on India or that India is the best bet for the United States in the Indo-Pacific.76 However, it is clear that the leaders of both countries have continued to increase their investments in their bets on each other. Modi being welcomed in the United States in a special way at this time is yet another step in this direction.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges and thanks Ashima Singh for her significant research assistance and for helpful editorial comments on earlier drafts. The author also acknowledges and thanks NatStrat for allowing the reuse of a few passages from his previous work, “US-India Relations: New Directions, Old Differences.”

1“Remarks by the President to the Indian Joint Session of Parliament,” The White House, March 22, 2000, https://clintonwhitehouse5.archives.gov/textonly/WH/new/SouthAsia/speeches/20000322.html

2“Text of Remarks Prepared for Delivery by Texas Gov. George W. Bush at Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Simi Valley, Calif. on November 19, 1999,” Washington Post, November 19, 1999, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/technology/1999/11/19/text-of-remarks-prepared-for-delivery-by-texas-gov-george-w-bush-at-ronald-reagan-presidential-library-simi-valley-calif-on-november-19-1999/1e893802-88ce-40de-bcf7-a4e1b6393ad2/.

3“U.S. - India: Civil Nuclear Cooperation,” U.S. Department of State, accessed June 2, 2023, https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/sca/c17361.htm.

4“President Bush Meets With Prime Minister Singh of India,” U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, accessed June 2, 2023, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2008/09/20080925-11.html.

5Joe Klein, “The Full Obama Interview,” TIME, October 23, 2008, https://swampland.time.com/2008/10/23/the_full_obama_interview/.

6 “Manmohan Singh as First State Visitor of Obama Presidency No Accident: US,” Hindustan Times, November 6, 2009, https://www.hindustantimes.com/world/manmohan-singh-as-first-state-visitor-of-obama-presidency-no-accident-us/story-E5JUriLT7b2UERF8jzrF5L.html.

7David Brunnstrom, and Steve Holland, “Obama Invites Modi to Visit U.S. Despite Past Visa Ban,” Reuters, May 16, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-modi-obama-call-idINKBN0DW1NY20140516.

8 “‘Obama’s India Visit Reflective of “Very Big Change” in Ties,’” Economic Times, updated January 21, 2015, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/obamas-india-visit-reflective-of-very-big-change-in-ties/articleshow/45968433.cms?from=mdr.

9 “U.S. Security Cooperation with India - United States Department of State,” U.S. Department of State, January 14, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-india/.

10The Economic Times, “’Abki Baar, Trump Sarkar,’” YouTube video, posted October 27, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogg2Hf9Qia0.

11Al Jazeera, “‘Howdy, Modi!’: Trump Attends Indian PM’s Rally in Houston,” September 22, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/9/22/howdy-modi-trump-attends-indian-pms-rally-in-houston.

12 Isabel Togoh, “‘Namaste Trump’: 100,000 People Turn Out to Welcome U.S. President at Start Of India Trip,” Forbes, February 24, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/isabeltogoh/2020/02/24/namaste-trump-100000-people-turn-out-to-welcome-trump-at-start-of-india-trip/?sh=4d774e8c5151.

13“India, USA and the World: Let Us Work Together to Solve the Political-Economic Y2K Problem,” Asia Society, September 28, 1998, https://asiasociety.org/india-usa-and-world-let-us-work-together-solve-political-economic-y2k-problem

14“PM Proves Mettle, Braves Nuclear Heat,” Reuters, July 23, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-34629420080723

15Shubhajit Roy, “US President Biden to Host PM Narendra Modi for State Visit in June,” Indian Express, May 10, 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/president-biden-host-pm-narendra-modi-official-state-visit-to-us-8602478/>https://indianexpress.com/article/india/president-biden-host-pm-narendra-modi-official-state-visit-to-us-8602478/. See also Arun Singh, “US-India Relations: New Directions, Old Differences,” NatStrat, Centre for Research on Strategic and Security Issues, June 6, 2023, https://natstrat.org/articledetail/publications/us-india-relations-new-directions-old-differences-74.html

16Suhasini Haidar, “A Long-Drawn Test for India’s Diplomatic Skills,” The Hindu, May 19, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/a-long-drawn-test-for-indias-diplomatic-skills/article66867396.ece

17Patricia Zengerle, “Indian PM Modi Invited to Address Joint Meeting of U.S. Congress on June 22,” Reuters, June 2, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/indian-pm-modi-invited-address-joint-meeting-us-congress-june-22-2023-06-02/

18 Vivian Yee, “At Madison Square Garden, Chants, Cheers and Roars for Modi,” The New York Times, September 28, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/29/nyregion/at-madison-square-garden-chants-cheers-and-roars-for-modi.html

19 “PM Modi in San Jose: 21st century belongs to India,” India Today, September 28, 2015, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pm-modi-in-san-jose-21st-century-belongs-to-india-265112-2015-09-28

20 Devesh Kapur, “The Indian prime minister and Trump addressed a Houston rally. Who was signaling what?” The Washington Post, September 29, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/09/29/prime-minister-modi-india-donald-trump-addressed-huge-houston-rally-who-was-signaling-what/

21“Joint Statement During the Visit of Prime Minister to USA,” Prime Minister of India, September 30, 2014, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/joint-statement-during-the-visit-of-prime-minister-to-usa/.

22“Vision Statement for the U.S.-India Strategic Partnership - ‘Chalein Saath Saath: Forward Together We Go,’” U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, September 29, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/29/vision-statement-us-india-strategic-partnership-chalein-saath-saath-forw.

23“India-U.S. Delhi Declaration of Friendship,” Prime Minister of India, January 25, 2015, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/india-u-s-delhi-declaration-of-friendship/.

24“U.S.-India Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean Region,” National Archives and Records Administration, January 25, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/25/us-india-joint-strategic-vision-asia-pacific-and-indian-ocean-region.

25“Narendra Modi Speaks to Joint Session,” United States House of Representatives, accessed June 2, 2023, https://www.house.gov/feature-stories/2016-6-9-narendra-modi-speaks-to-joint-session.

26 Shubhajit Roy, “From Nehru to Manmohan Singh, Five Indian PMs Who Addressed US Congress before Narendra Modi,” Indian Express, June 3, 2016, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/pm-narendra-modi-us-visit-capitol-hill-address-2831386/.

27Divyanshu Dutta Roy, “Our Nations Have Overcome ‘Hesitations of History’: PM Modi to US Congress,” NDTV.com, June 9, 2016, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/pm-modi-to-address-us-law-makers-in-a-few-hours-10-facts-1416903.

28“Indo-US Relations: Hotline Between PMO and White House to Continue Post January 20,” Indian Express, January 10, 2017, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/hotline-between-pmo-and-white-house-to-continue-post-january-20-4467345/.

29George Gedda, “Biden Pushes End to India Sanctions,” AP News, August 27, 2001, https://apnews.com/article/7db49bd4371acb8b387e8a46f81f6b40.

30Aziz Haniffa, “‘In 2020 the Two Closest Nations in the World Will Be India and US,’” Rediff.com, December 5, 2006, https://www.rediff.com/news/2006/dec/05inter.htm.

31Raj Chengappa, “US Senate Approves Indo-US Nuclear Deal,” India Today, December 4, 2006, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/diplomacy/story/20061204-the-indo-us-nuclear-deal-massive-approval-by-us-senate-2006-784211-2006-12-03.

32Yashwant Raj, “Joe Biden Supported India-US Nuclear Deal, Bernie Sanders Didn’t,” Hindustan Times, March 7, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/joe-biden-supported-india-us-nuclear-deal-bernie-sanders-didn-t/story-c3JJPD3G63TTIJEqmWLOBN.html.

33“Remarks by Vice President Joe Biden on the U.S.-India Partnership at the Bombay Stock Exchange,” National Archives and Records Administration, July 24, 2013, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/24/remarks-vice-president-joe-biden-us-india-partnership-bombay-stock-excha.

34“Biden Seeks Restoration of Peoples’ Rights in Kashmir; Disappointed with CAA, NRC,” The Hindu, June 26, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/biden-seeks-restoration-of-peoples-rights-in-kashmir-disappointed-with-caa-nrc/article31921284.ece.

35Lalit K. Jha, “Joe Biden Believes India-US Partnership Is Defining Relationship of 21st Century,” Mint, November 8, 2020, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/joe-biden-believes-india-us-partnership-is-defining-relationship-of-21st-century-11604797882771.html.

36 ANI News, "Joe Biden wishes Indian Americans on Independence Day," YouTube video, posted August 16, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0McXHC06YZ8.

37“India-US Ties: Joe Biden Plans to Strengthen Partnership between Two Nations,” Business Today, November 8, 2020, https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy-politics/story/india-us-ties-joe-biden-plans-to-strengthen-partnership-between-two-nations-278183-2020-11-08.

38Yashwant Raj, “Joe Biden Offers Full-Throated Support to India Against China, Pakistan,” Hindustan Times, August 15, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/joe-biden-offers-full-throated-support-to-india-against-china-pakistan/story-QXXDd5Wxyp7KlhXq0A4mON.html.

39“India-US Ties: Joe Biden Plans to Strengthen Partnership Between Two Nations,” Business Today.

40“Presidential Debate at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee,” The American Presidency Project, October 22, 2020, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/presidential-debate-belmont-university-nashville-tennessee-0.

41Joe Biden (@JoeBiden), “President Trump called India ‘filthy.’ It’s not how you talk about friends—and it’s not how you solve global challenges like climate change. @kamalaharris and I deeply value our partnership–and will put respect back at the center of our foreign policy,” Twitter post, October 24, 2020, 3:15 p.m., https://twitter.com/JoeBiden/status/1320081374448025600?s=20.

42 Raymond E. Vickery, “Joe Biden Is Better for India – If Democratic Values Are What Matters Most in US-India Ties,” The Diplomat, September 11, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/09/joe-biden-is-better-for-india-if-democratic-values-are-what-matters-most-in-us-india-ties/.

43 “Joe Biden Extends Greetings on Independence Day with a Swipe at Donald Trump,” NDTV.com, August 15, 2020, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/joe-biden-extends-greetings-on-independence-day-with-a-swipe-at-donald-trump-2280119.

44 “Joe Biden Extends Greetings on Independence Day with a Swipe at Donald Trump,” NDTV.com

45“Telephone Conversation Between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and His Excellency Joseph R. Biden, President-Elect of the United States of America, 17th November 2020,” Embassy of India, Moscow, Russia, https://indianembassy-moscow.gov.in/press-releases-pm-17-11-2020-1.php.

46 “Readout of President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Call with Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India,” The White House, February 8, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/02/08/readout-of-president-joseph-r-biden-jr-call-with-prime-minister-narendra-modi-of-india/.

47“Readout of President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.. Call with Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India,” The White House.

48“Readout of President Biden’s Call with Prime Minister Modi of India,” The White House.

49“Readout of President Biden’s Call with Prime Minister Modi of India,” The White House.

50“U.S.-India Joint Statement on Launching the ‘U.S.-India Climate and Clean Energy Agenda 2030 Partnership,’” U.S. Department of State, April 22, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-india-joint-statement-on-launching-the-u-s-india-climate-and-clean-energy-agenda-2030-partnership/.

51“U.S.-INDIA STRATEGIC CLEAN ENERGY PARTNERSHIPU.S.-India Strategic Clean Energy Partnership: Renewable Energy Pillar,” Department of Energy, October 2022, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/SCEP%20RE%20Pillar%20FINAL.pdf.

52“India and US Launch the Climate Action and Finance Mobilization Dialogue (CAFMD),” Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, September 13, 2021, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1754590.

53“Fact Sheet: Quad Leaders’ Summit,” The White House, September 24, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/24/fact-sheet-quad-leaders-summit/.

54“U.S.-India Joint Leaders’ Statement: A Partnership for Global Good,” The White House, September 24, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/24/u-s-india-joint-leaders-statement-a-partnership-for-global-good/.

55“FACT SHEET: United States and India Elevate Strategic Partnership with the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET),” The White House, January 31, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/01/31/fact-sheet-united-states-and-india-elevate-strategic-partnership-with-the-initiative-on-critical-and-emerging-technology-icet/.

56“Joint Statement of the Leaders of India, Israel, United Arab Emirates, and the United States (I2U2),” The White House, July 14, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/07/14/joint-statement-of-the-leaders-of-india-israel-united-arab-emirates-and-the-united-states-i2u2/.

57 “I2U2 Grouping of India, Israel, UAE and U.S. to Re-Energise American Alliances Globally: White House,” The Hindu, June 15, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/i2u2-grouping-of-india-israel-uae-and-us-to-re-energise-american-alliances-globally-white-house/article65529530.ece.

58Maayan Lubell and Nidhi Verma, “UAE Invests $2 BLN in Hi-Tech Indian Crop-Growing ‘Food Parks’ to Ease Shortages,” Reuters, July 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/uae-announces-2-billion-investment-india-food-parks-2022-07-14/.

59“Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” The White House, March 3, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf.

60 “Integrated Country Strategy India,” U.S. Department of State, May 27, 2022, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ICS_SCA_India_Public.pdf.

61 “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” The White House, Executive Office of the President National Security Council, February 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf.

62“National Security Strategy,” The White House, October 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

63“2022 National Defense Strategy of The United States of America,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF.

64Clea Caulcutt, “France Aims to Lure India from Its Main Arms Dealer: Russia,” POLITICO, November 28, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-eyes-opportunity-for-geopolitical-realignment-in-india-indo-pacific-russia-arms-modi-macron-putin-g20; and Arun Singh, “US-India Relations: New Directions, Old Differences.”

65 “Secretary Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar, and Indian Minister of Defense Rajnath Singh at a Joint Press Availability,” U.S. Department of State, April 11, 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-austin-indian-minister-of-external-affairs-dr-s-jaishankar-and-indian-minister-of-defense-rajnath-singh-at-a-joint-press-availability/.

66Sriram Lakshman, “U.S. Playing a ‘Long Game’ in Relationship with India: Jake Sullivan,” The Hindu, June 16, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/us-playing-a-long-game-in-relationship-with-india-sullivan/article65534106.ece.

67“Respect Territorial Integrity, Sovereignty of All: PM Modi at G7,” Times of India, May 22, 2023, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/respect-territorial-integrity-sovereignty-of-all-pm-modi-at-g7/articleshow/100403410.cms?from=mdr.

68“‘Today’s Era Not of War’: How India United G20 on PM Modi’s Idea of Peace,” Times of India, accessed June 2, 2023, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/todays-era-not-of-war-how-india-united-g20-on-pm-modis-idea-of-peace/articleshow/95552042.cms.

69Asfandyar Mir, “Pakistan’s Twin Taliban Problem,” United States Institute of Peace, May 4, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/05/pakistans-twin-taliban-problem.

70“Raksha Mantri’s Telephonic Conversation with US Secretary of Defence,” Press Information Bureau, Government of India, September 14, 2022, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1859301.

71Hormaz Fatakia, "India Ideas Summit 2023: Indian companies support over 4 lakh jobs in the US, says Secretary of State Antony Blinken," CNBC TV18, June 13, 2023, https://www.cnbctv18.com/economy/india-ideas-summit-2023-antony-blinken-address-indian-companies-job-creation-air-india-boeing-it-pharma-40-billion-16915771.htm.

72“Over 200,000 Students Went to US for Higher Studies in 2021-22: Report,” Business Standard, November 14, 2022, https://www.business-standard.com/article/education/over-2-lakh-students-went-to-us-for-higher-studies-in-2021-22-report-122111401454_1.html.

73Arun Singh, “US-India Relations: New Directions, Old Differences.

74 Seema Sirohi, “Why PM Narendra Modi’s Upcoming US Trip Could Be as Pathbreaking as Manmohan Singh’s 2005 Visit,” Economic Times, updated May 29, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/et-commentary/why-pm-narendra-modis-upcoming-us-trip-could-be-as-pathbreaking-as-manmohan-singhs-2005-visit/articleshow/100574902.cms.

75Ashley J. Tellis, “America’s Bad Bet on India,” Foreign Affairs, May 1, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/india/americas-bad-bet-india-modi.

76Arzan Tarapore, “America’s Best Bet in the Indo-Pacific,” Foreign Affairs, May 29, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/americas-best-bet-indo-pacific.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

The second International AI Safety Report is the next iteration of the comprehensive review of latest scientific research on the capabilities and risks of general-purpose AI systems. It represents the largest global collaboration on AI safety to date.

Scott Singer, Jane Munga

A close study of five crises makes clear that Cold War logic doesn’t apply to the South Asia nuclear powers.

Moeed Yusuf, Rizwan Zeb

On January 12, 2026, India's "workhorse," the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, experienced a consecutive mission failure for the first time in its history. This commentary explores the implications of this incident on India’s space sector and how India can effectively address issues stemming from the incident.

Tejas Bharadwaj

As European leadership prepares for the sixteenth EU-India Summit, both sides must reckon with trade-offs in order to secure a mutually beneficial Free Trade Agreement.

Dinakar Peri