The United States, Russia, and China are intensifying their competition for global influence. Our analysis reveals that their involvement and impact vary across the Middle East and North Africa. Within subregions, the three powers assert their influence in the realms of economy, security, and diplomacy, achieving various degrees of success.

Russia in the Middle East and North Africa—Disrupting Washington’s Influence and Redefining Moscow’s Global Role

The agency of MENA states and nonstate actors and their multilayered interactions with the United States, China, Russia, and the EU have helped shape the complex outcomes of the great power competition.

Introduction

Faced with various threats and conflicts ranging from the persistence of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the danger of a wider regional war to the rise of nonstate actors that systematically use violence in internal and external conflicts, today’s Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries are drawing in China and Russia to compete with the United States over military presence, arms sales, energy and trade ties, and security roles. At the same time, most European Union (EU) member states have come to define their roles as allies of the United States and to focus their policies on trade and immigration questions. The resulting regional environment is characterized by greater agency for MENA states and nonstate actors.

On the one hand, the geostrategic and energy significance of the MENA region, the risks the region poses to global security, its economic opportunities, and young populations have drawn all great powers to its shores in search of political influence and trade and investment opportunities, as well as to protect security interests. Outcomes have varied across the Middle East and North Africa, creating a complex influence map that does not lend itself to sweeping generalizations. On the other hand, the agency of MENA states and nonstate actors and their multilayered interactions with the United States, China, Russia, and the EU have helped shape the complex outcomes of the great power competition. Analyzing the minutiae of those multilayered interactions and examining the nature and impact of regional agency are the core tasks of this research project.

The United States, China, Russia, and the EU have core interests in the MENA region. The United States has always worked to safeguard Israel’s security and to maintain a degree of regional stability. China has grown increasingly preoccupied with securing energy supplies coming from the Gulf while still freeriding on the U.S. role to ensure the flow of energy and trade out of the region and across it. Since the decline in its regional role following the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has been deeply invested in protecting its few remaining allies in the region and in disrupting the United States-led regional security arrangements. EU member states want to secure their trade and investment strongholds in the MENA region as well as contain migration from the region to the northern shores of the Mediterranean.

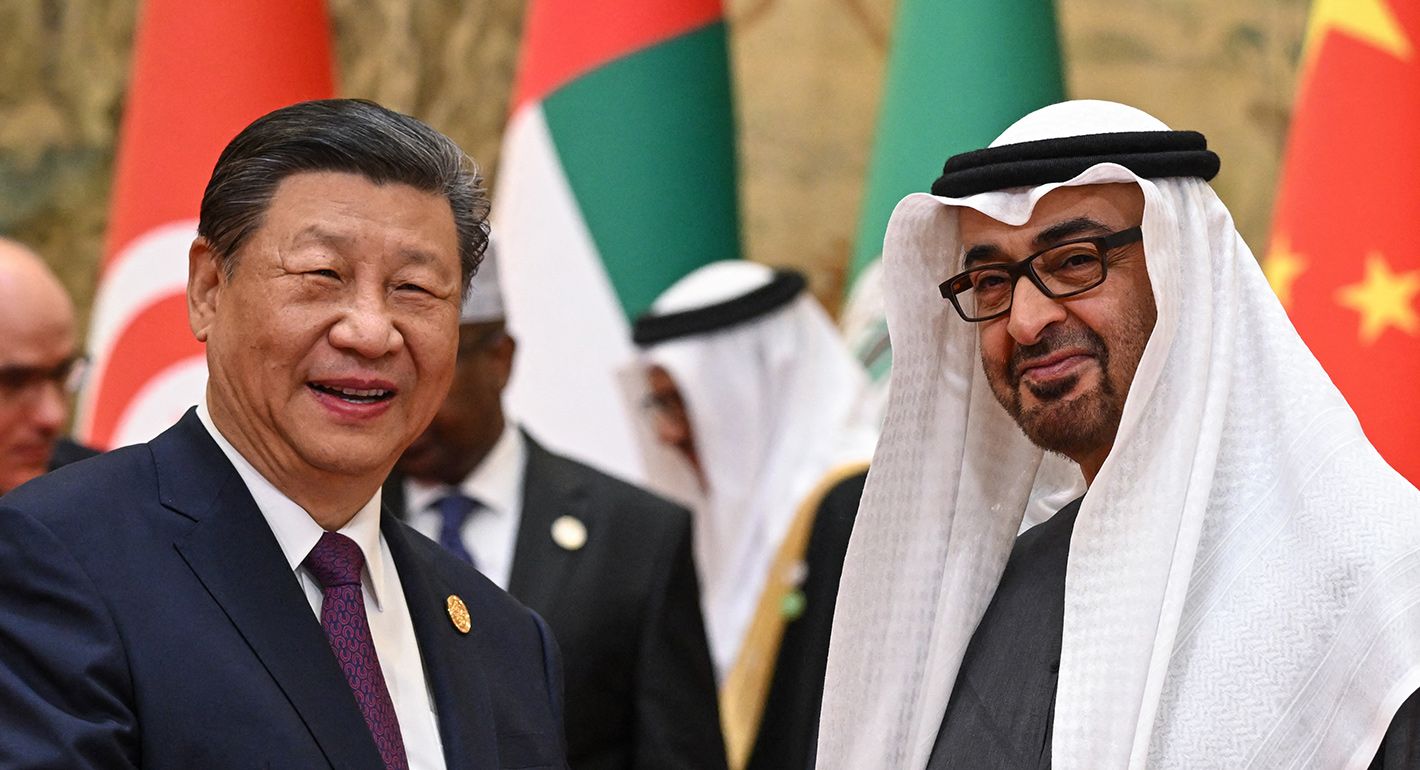

In recent years, following much talk in U.S. policy circles about the pivot to Asia and the low return on America’s continued involvement in the MENA region, conventional wisdom in Washington has often described recent U.S. Middle East posturing as signaling retreat or withdrawal, while still remaining wary of how China or Russia may take advantage of the “vacuum” left behind and of a declining EU role as a result. The 2023 Beijing-brokered détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia is often waved as sweeping evidence. However, realities on the ground, not only in the aftermath of the October 7, 2023, attacks on Israel and the ensuing Gaza War, reveal the need for a more nuanced analysis, as different engagement patterns and interactions between the great powers and MENA state and nonstate actors have emerged.

Russia and Other Great Powers in the MENA Region

During a one-year pilot project, the Middle East Program (MEP) at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace produced aninteractive database that tracks and analyzes how the United States, China, and Russia assert their influence in the realms of economy, security, and diplomacy in the MENA region. The data, provided on a country-by-country basis, are intended to shed light on broad trends and show how each of the great powers engages in the region. Within the database, we identify trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), arms exports, and military deployment as four indicators to show trends of engagement with each subregion. Despite the perception that U.S. power is declining in the Middle East and North Africa, the data show that is not the case: the reality is much more nuanced.

Our analysis revealed that American hegemony has been reinforced through a regional network of military bases, security guarantees, and widespread diplomatic and cultural influence. In a similar vein, China’s global rise is also evident in the MENA region through their trade, technology, economic, and diplomatic ties. In recent years, the industrial and trade giant has advanced to become a big player in regional politics, leveraging its strong ties with most Arab countries, Israel, Türkiye, and Iran. Russia, traditionally an influential power in parts of the Middle East and North Africa, has made a geostrategic comeback in recent years. Although Russian trade, FDI, arms exports, and military deployments have remained relatively low in the MENA region compared to those of the United States and China, Russian policies have nonetheless shaped geostrategic realities, particularly in Syria, Libya, and more recently Sudan.

In this compilation, MEP scholars together with Carnegie experts from across its global institutions and external contributors delve deeper into Russian policies in the MENA region. Their pieces cover the historical evolution of Russia’s foray to the region in the second half of the twentieth century, similarities and differences between past (Soviet) and present policies, and the role arms sales and trade relations play in shaping Russia’s role in the Levant, the Gulf, Egypt, and North Africa. They also address the strategic framing of Russian policies in the MENA region and how they relate to Moscow’s global competition with the United States and its quest for a great power role.

Forward Looking Research

Moving forward, MEP scholars, in a series of papers slated to be published in 2025, will examine how the competition between the great powers in the MENA region is affecting the foreign policies of major regional states and the ways in which countries such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Israel, Iran, Türkiye, and the United Arab Emirates leverage their strategic assets to address their security and developmental needs in a geopolitical environment shaped by threats, risks, and opportunities.

In this new phase of our research, we will include the European Union (EU) as a great power alongside the United States, China, and Russia. Although its member states lack a unified policy towards the MENA region, the EU has been a key trade, security, and diplomatic partner for MENA countries and occasionally influenced the outcomes of regional conflicts and crises.

MEP scholars will investigate how interactions between the great powers and key regional states and nonstate actors are changing geopolitical realities in the region and facing existing security arrangements and conflict resolution schemes with new challenges that need to be understood, analyzed, and addressed. We believe that short of doing this, the fragile peace in some parts of the Middle East and North Africa will be difficult to preserve and ongoing conflicts in many parts may spiral more out of control.

We will ask how the great power competition is affecting the foreign policies of key regional states, how nonstate and substate actors are responding to the geopolitical shifts wrought by regional and global events such as the ongoing wars in Gaza and Ukraine, and how U.S., Chinese, Russian, and European policies are impacting societal views of the great powers in the MENA region. We also address other key questions such as how regional states and nonstate actors are reconfiguring their policies to consider the great power competition, and how Middle Eastern and North African public opinion trends change vis-à-vis the great powers, and what impacts do these shifts and changes have on the soft power of the United States, China, Russia, and the EU.

Our goal is to increase knowledge of relevant security policy issues, including conventional, nonconventional, and hybrid threats and challenges, with a view toward improving inclusion, good governance, and bolstering the resilience of the MENA region’s most vulnerable citizens. We aim to offer sound policy analyses and prescriptions that can help preempt geopolitical conflict and improve the quality of life of citizens.

Despite the dichotomy between ideological, Soviet-era support for anti-Western regimes and interest-driven Putin-era support, there are several similarities.

Mark N. Katz

Russia’s military intervention in Syria reflected a more assertive foreign policy. However, its ability to expand its influence to Lebanon and beyond has been restricted.

By aligning with Russia occasionally, Egypt not only mitigates the impact of fluctuating U.S. support but also extracts concessions and benefits from both the United States and Russia.

Russia’s outreach to the region has successfully exploited regimes’ frustrations with the West. Yet it has encountered difficulties in navigating the complex interrelations and rivalries.

A common adversary has brought these natural rivals together.

China and Russia face different trajectories in the Gulf. These trajectories will be shaped by prevailing strategic interests and influence, which are evolving and can shift abruptly.

Robert Mogielnicki

The multifaceted nature of Turkish-Russian relations is tied to Türkiye’s changing relations with the West and its strategic maneuvers for greater autonomy.

The Kremlin’s Middle East diplomacy is driven by its rivalry with the West, the imperative to defend deep-rooted Russian interests in the region, and a desire to project power and influence well beyond its periphery.

Russia has largely inherited the Soviet Union’s Middle East foreign policy. China may be best positioned to take advantage of this historical relationship.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Trump-Modi Trade Deal Won’t Magically Restore U.S.-India TrustCommentary

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- From Loss and Damage to Climate Mobility ActionCommentary

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

- Europe Falls Behind in the South Caucasus Connectivity RaceCommentary

The EU lacks leadership and strategic planning in the South Caucasus, while the United States is leading the charge. To secure its geopolitical interests, Brussels must invest in new connectivity for the region.

Zaur Shiriyev

- Russia Won’t Give Up Its Influence in Armenia Without a FightCommentary

Instead of a guaranteed ally, the Kremlin now perceives Armenia as yet another hybrid battlefield where it is fighting the West.

Mikayel Zolyan

- The United States Should Apply the Arab Spring’s Lessons to Its Iran ResponseCommentary

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes