Stretching from the arid scrublands and dune seas of the Sahara to the forested coastlines of the Mediterranean and the high, snow-capped peaks of the Atlas Mountains, the Kingdom of Morocco presents a picture of striking contrasts—and a paradox regarding its progress on climate change mitigation and adaptation.

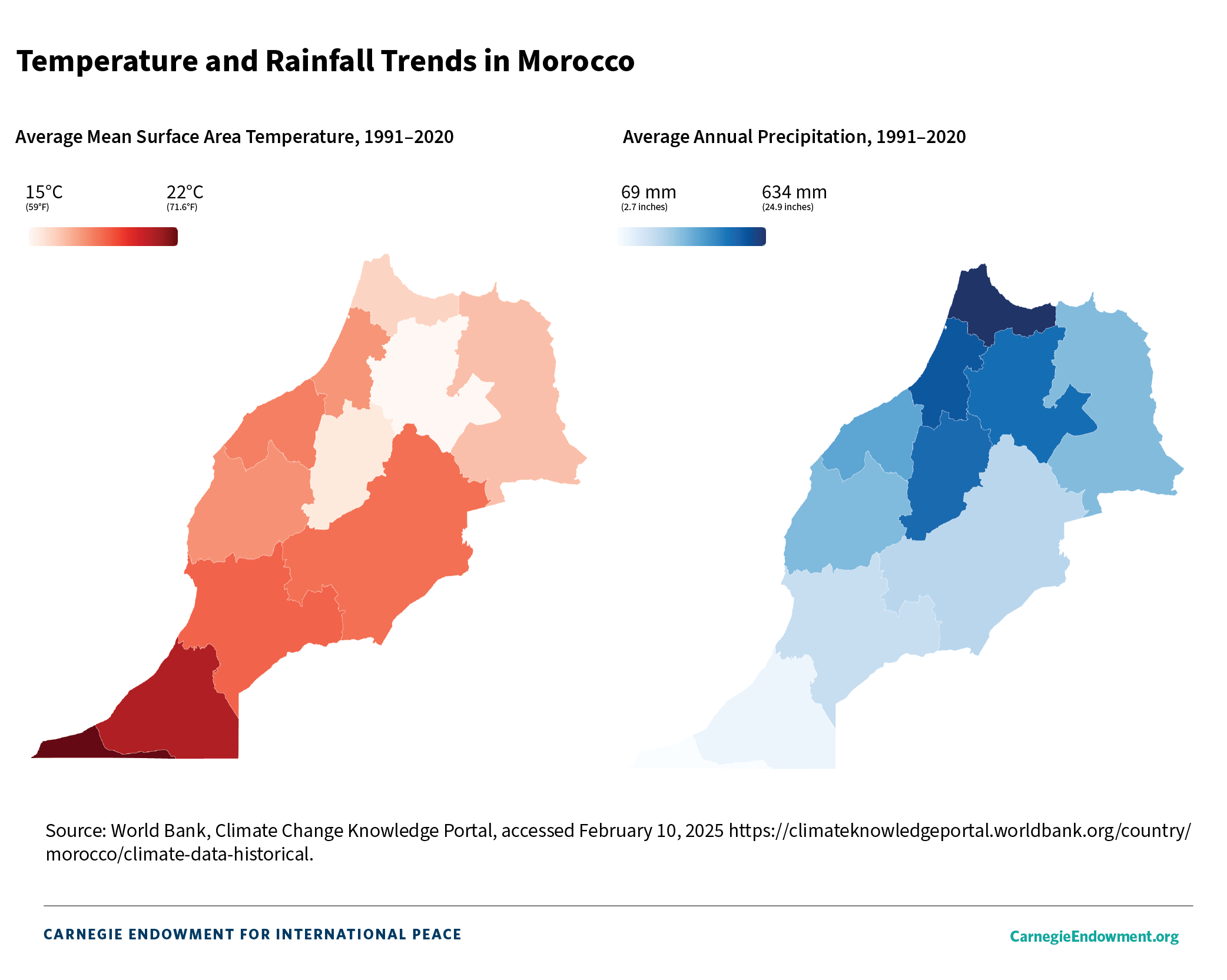

Despite suffering from severe exposure to climate change stresses such as rising temperatures, decreasing rainfall, and worsening droughts, Morocco is relatively well-equipped and well-prepared to meet the challenges of climate adaptation and the imperatives of the green energy transition. The Climate Change Performance Index, widely cited by the government in Rabat, places Morocco as the eighth most climate-prepared country in the world. According to the University of Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative’s index, Morocco is the fifty-fifth most climate vulnerable country and the eighty-seventh most ready country, meaning that “while it faces adaptation challenges, it is well positioned to address them.”

To be sure, there are grounds for these plaudits. To begin with, Morocco is endowed with resources that could make it a regional and even global leader in renewable energy: it has competitive wind speeds; generous reserves of battery materials; and vast swathes of sun-washed land ideal for solar power generation. Accordingly, multinational company Ernst & Young ranked Morocco as second globally in a 2023 normalized index of Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness. The neighboring states of the European Union, eager to wean themselves off fossil fuels and their dependence on Russian gas exports, are enthusiastically consuming renewable energy produced by their North African neighbor, and Morocco has plans to expand this relationship with the construction of a high-voltage direct current cable between itself and Europe. Further afield, China relies on Morocco’s phosphate exports to produce batteries essential to its electric vehicle strategy.

At home, meanwhile, the Morocco government has set forth an admirable and ambitious agenda to harness its renewable energy potential, to compensate for its severe lack of hydrocarbon reserves.1 Moroccan policymakers were among the earliest and most committed supporters of global efforts to combat climate change, ratifying the 1995 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the 2002 Kyoto Protocol, and the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement.2 Among the signatories of the latter pact, Morocco distinguished itself by setting the second-highest carbon reduction goal in its Nationally Determined Contribution of any country in the Middle East and North Africa. Outlined in the National Climate Plan 2020–2030, Morocco’s energy transition plans include, among other initiatives, a Green Hydrogen Strategy and the goal of reducing emissions by over 40 percent by 2030. During COP 28, Morocco launched its National Low Carbon Strategy 2050, which aims for carbon neutrality by 2050 through the construction of wind and solar farms; electrifying transportation, buildings, and industry; bolstering recycling efforts; developing sustainable agriculture; and promoting a series of so-called intelligent cities. Already, the results of the transition to renewables have been impressive: in just eleven years, Morocco has seen a sixteen-fold increase in solar capacity and sixfold increase in wind capacity.3

And yet, behind this well-known narrative of Morocco’s commitment to carbon reduction benchmarks and progress on the renewable energy front, there is another, less-known climate story.4 It’s the story of how global warming is already endangering the economic security, livelihoods, and physical well-being of millions of people in Morocco, especially its most vulnerable citizens, including rural inhabitants, smallholder farmers, and oasis dwellers and nomads. On top of this, the Moroccan government’s much-touted initiatives on green energy technology are overshadowed by the fact that, despite all the fanfare, the country still relies heavily on fossil fuels—a dependence that has contributed to the doubling of its energy bills after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its persistently high levels of greenhouse gas emissions.

While ultimately rooted in the country’s severe aridity and shortage of replenishable water sources, Morocco’s climate change vulnerabilities have been worsened by long-standing governance deficiencies, especially unsustainable agricultural policies centered on profitable, water-intensive crops that have historically benefited regime-connected landowners with narrow interests while excluding more vulnerable populations. Climate-friendly energy projects have often failed to reach their full potential because of mismanagement and poor interagency coordination, and some of Morocco’s stated plans to mitigate climate problems run the risk of augmenting rather than ameliorating these vulnerabilities. For example, to diversify its energy sources, Morocco will use water to further its green hydrogen plans, but doing so will seriously strain an already scarce resource.5 Additionally, climate-related stresses in Morocco are exacerbated by the long shadow of French colonialism in the water management and agricultural sectors, which bequeathed to the country what one Moroccan scholar called an “irrigation myth” of cultivating water-intense crops in an arid environment that has left its smallholder farmers and other rural inhabitants acutely exposed to global warming.6 And the government’s ability to protect communities in remote areas from climate stresses has been hobbled by the obstacles confronting local civil society actors, which prevent them from representing vulnerable citizens and effectively mobilizing on climate adaptation.

Field interviews with Moroccan farmers, activists, crop specialists, and climate scientists point to the need for a better understanding of how worsening climate stresses and the kingdom’s governance shortcomings on water management and agricultural policy—especially the absence of local-level empowerment—are inextricably linked. Most pressingly, they highlight that durable, effective climate adaptation requires a greater inclusion of independent grassroots actors in political discussions and decisionmaking to bolster and expand top-down, national-level efforts on the renewable energy front.

The Climate Vulnerability-Governance Nexus

There is no question that environmental factors in Morocco carry much of the blame for the injurious impacts of climate change on the country’s vulnerable populations. Ninety-three percent of Morocco’s land qualifies as arid or semi-arid. Desertification is steadily creeping northward, and droughts of increasing magnitude and frequency have worsened this phenomenon. Since 1980, Morocco has experienced twelve major droughts, with the current and longest drought having entered its seventh year in 2025. Heat waves have also increased, reducing harvest yields and igniting wildfires that deplete Morocco’s tree cover. Adding to this situation is the current paucity of water: the World Resource Institute ranks Morocco among the countries with “high” water stress, meaning those that are using between 40 and 80 percent of their available water. Of the water that does exist, 80 percent of it is drawn from surface reservoirs, such as dams, making this essential resource acutely vulnerable to climate-induced dynamics of decreased precipitation and increased temperatures.7

Yet the impacts of these natural and environmental stresses related to climate change have been magnified and worsened by short-sighted government policies and entrenched socioeconomic inequalities, particularly in the agricultural and water management sector. The roots of these deficiencies, Moroccan activists and scientists say, can be partly found in the policies pursued by French colonial administrators during the first decades of the twentieth century. French colonizers drastically transformed Morocco’s agricultural landscape and habits of water usage, as well as transferred to the country’s independent rulers a deeply unequal system of resource extraction. This scheme of water- and land-usage clientelism endures to the present, impeding Morocco’s progress on climate adaptation.

The template employed in this colonial strategy was deliberately and systematically borrowed from California. The French saw California as comparing favorably to Morocco in terms of its latitude, semi-arid climate zones, soil fertility, precipitation ranges, and availability of cheap farming labor. In the case of California, the labor force included, at various times, Chinese, Japanese, Indigenous, Mexican, and Filipino workers, and, in the case of the North African protectorate, Arab and Amazigh peasants. Eager to exploit what they saw as Morocco’s untapped potential as an export breadbasket, the French government dispatched teams of hydraulic engineers and agricultural specialists to California’s Central Valley. There, the scientists studied how pipelines, aqueducts, and dams could maximally direct rainfall, rivers, and groundwater to large-scale irrigation for profitable but water-intensive citrus crops—oranges, tangerines, lemons, and grapefruits, among others—along with many other fruits and vegetables. By the 1930s, the California model had been fully embraced by the French in Morocco, and its legacy continued to be felt long after the country’s independence in 1956, in the expansion of vast swathes of orchards and fields whose high-value output of fruits eventually comprised over a third of agricultural exports.

Today, citrus fruits, watermelons, avocados, sugar beets, and tomatoes grow bountifully in Morocco. Yet these heavily water-consuming crops are having an increasingly negative impact on the agrarian economies in key rural regions and their associated labor force, given the unsustainable pace of water extraction and declining rates of rainfall due to global warming. Exemplifying this dynamic, farmers in southern Morocco were recently compelled to destroy their citrus orchards because the trees required five times more water than is provided by rainfall.8 Elsewhere, Morocco’s dairy farms, another inheritance from the French’s modeling of Morocco after California, are also suffering from climate-induced shortages of precipitation, since they too demand exorbitant amounts of water: producing one liter of milk in Morocco—where smallholder farms often produce both milk and meat simultaneously—usually requires 1,500 liters of water, and at the same time, one kilogram of beef requires 16,500 liters of water.9 Taken in sum, these stresses point to a fundamental mismatch between Morocco’s natural endowments of resources and the agricultural techniques imposed by the country’s former colonial rulers, which, in the face of recent global warming, are now depleting Morocco’s water supply faster than it can be replenished.

Deepened social inequalities in rural areas are another legacy of the colonial period. The growth of industrial-scale agriculture under the French pushed out smallholder farmers and oasis dwellers, forcing them to relocate to cities. The displaced persons included those who practiced more traditional—and sustainable—crop raising using the khettara system, which relies on gravity and underground pipes to harvest subterranean water for irrigation. Meanwhile, wealthy countryside elites emerged as especially big winners. Over a two-decade period, they received hundreds of thousands of hectares of agricultural land from the French colonialists, who still exercised legal control over these territories even after Morocco’s formal declaration of sovereignty.

The inequities resulting from this policy persisted and worsened long after the French departed, as the country’s new rulers and their allies consolidated their power. Starting in the 1960s, landowning elites received further privileges from King Hassan II, who saw them as a bulwark against an urban-based opposition movement fueled by the middle class. Most notably, the king used the construction of dams to further solidify the loyalty of these elites, by increasing the crop yields of the farms they oversaw. The number of dams skyrocketed from thirteen at the time of independence to over 100 by the end of Hassan II’s reign in 1999. To be sure, the dams addressed a real economic need, especially in the south, where precipitation was far less frequent and predictable than in the north. But in many instances, it was the pro-regime landowners who benefitted the most.10

For the vulnerable communities who have suffered from this cutoff, Morocco’s dams stand as hulking concrete memorials to short-sighted water and agricultural policies that have privileged profits for the few over a more equitable distribution of resources and a more sustainable strategy. As Morocco has entered its sixth consecutive year of drought, its average dam filling rate has dropped over 8 percent compared to the last year, with total levels varying between fully replenished and near-empty—a status that any Moroccan with a mobile phone can track through Mor Dam, a mobile application provided by the Ministry of Equipment and Water. Despite the dams’ depletion, the government has announced the construction of thirteen more. The dams containing water do provide some needed irrigation to farmlands, though their overall contribution is miniscule—roughly 750,000 of Morocco’s 7.5 million hectares of agricultural surface are fed by dams (though this has shrunk dramatically since the current drought’s onset), and salinity taints the nourishing value of this water. Moreover, access to what remains is unequal, with wealthy landowners and cities benefitting disproportionately. For example, dams alongside Wadi Shbooka, a valley in central Morocco, have enabled eight wealthy farmers to avoid the effects of drought, but less-powerful locals suffer from a consequential shortage of water for livestock, a depleted fish population, and general environmental ruin.

Lengthening droughts and an ever-shrinking water supply have spurred the government to supplement this long-standing dependency on dams with other sources of irrigation. However, the very same patterns of rural inequality have been perpetuated, with similarly deleterious results for sustainability and climate vulnerability. Most notably, a strategy for drip irrigation practices powered by groundwater wells—a shift that was prompted in part by the first of several droughts in the 1980s and refined in the 2008 agricultural plan known as Plan Maroc Vert—resulted in large landowners benefitting from sizeable subsidies for obtaining well-digging equipment. These elites exploited the government’s poor oversight, illegally digging private wells to maintain their income from profitable crops and to circumvent a water crisis, which poorer Moroccans could not avoid. Today, roughly 90 percent of Morocco’s 372,000 wells fall into this unauthorized category, resulting in unmonitored pumping and the further diminishment of aquifers’ water levels. “Forty years of groundwater depletion has brought us to the point where there simply are no more solutions,” noted Mohamed Taher Sraïri, a prominent agronomy specialist and university professor at the Hassan II Agronomy and Veterinary Institute in Rabat.11

More recently, this “hydraulic lobby” of government-connected landowners has attempted to steer Morocco’s strategy on climate adaptation. According to one prominent critic of the government’s agricultural policies, this lobby is influencing policies in government agencies, in parliament, and in local institutions. “For decades this lobby didn’t care about water questions; they acted like we are in Canada,” noted Najib Akesbi, a leading Moroccan economist, who also teaches at the Hassan II institute. “But now, they can see that their choices are incompatible with the availability of water. And so, since around 2018 or 2019, they have started taking an interest in the climate file.”12

Government Actions and Public Responses to Climate-Induced Water Scarcity

Faced with the looming crisis, the government has attempted to diversify Morocco’s water sources and improve water accessibility for the population, though unsustainability and inequalities also blight these efforts. The Moroccan government has made significant progress in expanding the accessibility of potable water to its population. According to government officials, access to liquid sanitation services increased from 96.5 percent to over 97 percent between 2016 and 2019. In drought-afflicted rural areas, solar generators could spur greater pumping of aquifers for drinking and irrigation water, but this is a short-term fix with long-term consequences for the already stressed water table.13 Additionally, expanding water access to more people does not equate to an increased quantity of this finite resource. In fact, quite the opposite has occurred. In the 1960s, Morocco’s water per capita was 2,560 cubic meters, but today the water per capita ratio is shockingly just 606 cubic meters. Cleaning and cooling solar panels in the Noor Ouarzazate Solar Power Station has further depleted potable water stores.

The Moroccan government has looked to desalinization to partly alleviate its water shortages. Desalinated water currently meets 3 percent of Morocco’s water needs, with eleven desalination plants already operational and nine more planned. By 2030, Morocco hopes that desalination facilities will produce 50 percent of Moroccans’ drinking water. But here again, while desalination offers some respite from the current and looming shortfall, it is not the panacea it is made out to be. Brine discharge and the accidental intake of marine life during the desalination process create considerable harm for local ecosystems. Morocco’s fisheries make up 58 percent of agro-food exports, so disruptions to marine life could have serious impacts on Morocco’s labor force. And while desalinization makes sense for producing drinking water, its cost makes it less appropriate for agricultural use; producing one cubic meter of water costs an estimated 10–15 Moroccan dirhams (approximately $1 to $1.5). Because of desalinated water’s high price, only the most lucrative crops such as avocado could use it without incurring net losses.14

In the legal realm, the privatization of water is perceived to be exacerbating this shortage. This policy has emerged as a contentious focal point of dissent and protest, especially since the enactment of Law 83.21 in 2023. Law 83.21 handed the provision of drinking water to regionally based, multiservice companies, acting in coordination with municipalities. An array of rights activists and farming advocates criticized the insufficient transparency and lack of substantive discussion that accompanied the passage of the bill, as well as the dire social consequences that could arise from its implementation during a period of sustained water shortages and worsening climate shocks. Several interviewees involved in advocacy for climate-imperiled communities pointed to the law’s commodification of a valuable public good that had hitherto been provided by the state and to the risk that the private interests of elites would, once again, take precedence over ordinary citizens’ welfare. “Before we could negotiate with the state, but now we have to deal with private companies,” noted one farmers’ union representative. “Before water was a public service, now it is ‘merchandized.’”15

The government has enacted patchy regulations to modulate demand in the face of water scarcity. But an effective response was late in coming. Only in 2017 did the Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests stop encouraging the cultivation of profitable, water-demanding crops. Watermelon production had constituted the primary income for many poor farmers in the town of Zagora, though persistent drought and the resultant depletion of water reservoirs were already cutting into their income. That year, protests erupted in the Zagora region over recurring household shortages of potable water due to the exorbitant extraction by nearby watermelon farms, resulting in arrests and prison sentences for some of the demonstrators.

Despite the events in Zagora and similar demonstrations in Beni Mellal in 2017, Talsint in 2018, and Imintanout in 2019, a formal shift in policy implementation did not occur until 2022. That year, the Ministry of Interior discontinued irrigation subsidies for watermelons, avocados, and citrus fruit and, a year later, drastically limited the production of watermelon in the area. In urban areas, meanwhile, the government implemented restrictive conservation measures, such as the closure of hammams (traditional public baths) and the shutdown of car washes for three-day stretches. Yet some climate specialists and activists argue that the overall effect of such measures is likely negligible due to the small share personal and industrial consumption takes in total water usage. In a further illustration of how the government’s water conservation directives entrench socioeconomic disparities, critics of these policies also point out that water use at spas and swimming pools at upscale hotels are exempt from the restrictions.

Elsewhere, misguided initiatives and wasteful implementation still stymie Morocco’s climate adaptation and mitigation activities. Many green energy projects end up having inadvertent, adverse effects on sustainability. In 2014, King Mohammed VI rolled out plans to increase urban green spaces in Rabat, yet this initiative ended up sapping an already stressed water supply as armies of gardeners planted unsustainable shrubbery. Water bills more than tripled for Rabat residents, so the municipal government quickly shifted to irrigating the spaces with wastewater. Additionally, under the direction of the minister of interior, the gardeners replaced existing palm trees with an imported species, the Washingtonia, which failed to cool the city as much as their native counterpart.16

A lack of coordination further inhibits Morocco’s climate progress. Weak collaboration between Morocco’s Ministry of Environment and the Ministries of Interior and Finance preceded the creation of the Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development, which in writing has the widest purview for green energy projects.17 In cities, the Ministry of Interior has the real power, but has minimal oversight or accountability. In more rural areas, the mayors of towns and villages have more authority than their counterparts in large cities, but they also have more problems to deal with and less money in their budgets. Appointed officials connected to the monarchy further complicate the effective delineation of funds, as they can rework budgets with minimal bureaucratic backlash. For example, the National Climate Change and Biodiversity Commission was created in April 2020 to promote coordination between different government entities, but there is still no definitive tool to monitor climate-related programs or spending. This disorganization is concerning, with one municipal official saying that he learned of the regime’s climate initiatives not through official channels but by seeing project implementation on the street or reading notices for public works.18 Furthermore, poor transparency makes many civil society actors unwilfully ignorant of the conditions attached to sizable international funding, such as the $1.3 billion combination of grants and loans issued by the International Monetary Fund in September 2023.19

Vulnerable Populations: Farmers, Nomads, and Oasis Dwellers

Climate change exacts an outsized toll on Morocco’s rural population, with farmers, oasis dwellers, nomads, and Amazigh communities particularly at risk. Only about 10 percent of Morocco’s GDP comes from agriculture, but around 30 percent of its population (approximately 11.4 million workers) are employed in this sector. In addition, hundreds of thousands of shopkeepers and tradespeople service the rural workforce that is engaged in farming and directly reliant upon crop yields. The Moroccan governments’ lack of transparency in recordkeeping makes estimations difficult, but based on the most recent census, conducted in 1996, roughly 70 percent of the farms in Morocco are small family farms with cultivable areas of less than 5 hectares; thus, it is households that ultimately suffer the most from climate-induced droughts and water shortages, rather than large landowners and corporations. Ironically, many smallholder, family-owned farms are engaged in more sustainable crop raising, which does not require the inordinate and often nonrenewable groundwater that the corporations’ and large landowners’ higher-value export crops depend upon.20 In the fertile northwest, these rain-fed crops include olives, grain, pulses, and alfalfa. To the south and east, rain vitalizes additional grain crops, grasses for grazing, and, in the southern slopes of the Atlas Mountains, dates.

Yet climate-induced drought and water shortages—exacerbated by an ineffective government response—are taking their toll on these crops and the livelihoods of their cultivators. Interviews with Moroccans involved in agriculture underscore the severe economic, social, and mental health costs of this plight, which often involves families abandoning a way of life that had been practiced by generations of their ancestors. For many, there is the profound sense that while dry spells and bad harvests are an inevitable hazard of the farming vocation, there is something qualitatively different about the recent wave of heat and diminishing precipitation. “Many farmers are not talking about climate change per se,” noted a unionist and farmer. “A ‘drought is a drought’ and ‘a flood is a flood,’” in their view. But even the older ones say, “We have never seen anything like this.”21 Echoing this sentiment, Siham Rahmoune, a farmer and head of a women’s cooperative from the city of El Jadida, pointed to the cumulative effects of climate stresses and government inaction:

Speaking of my own experience, when the years of drought and high temperatures continued . . . despite all the fatigue and effort, I didn’t get a crop. Of course, you can imagine this because all small farmers are suffering from this issue. . . . I live from my work . . . [and] I lost a lot. I was on the verge of bankruptcy. . . . I didn’t get any help [from the government].22

Other interlocutors pointed to the far-reaching social effects of climate change on family cohesion and welfare. A labor union representative who works extensively with afflicted farmers pointed to the deleterious effects on children, with water shortages extending the time it takes to fetch water and herd livestock—tasks undertaken typically by school-age girls and boys, respectively.23 Another farming advocate pointed to an increase in divorces in farming families due to declining incomes and the long periods of separation that arise when sustained droughts force male heads of households to relocate for work.24

More directly, natural environmental degradation harms the physical health of rural Moroccans. One survey described Morocco as the third least healthy environment in the world due to climate change, surpassed only by Iran and Equatorial New Guinea. As the water table decreases, so do Moroccans’ access to clean drinking water. Suffering from the paucity of this vital resource and confronting declining prospects for work, many rural inhabitants have moved to urban centers, only to confront overcrowded conditions and, in some instances, poor access to water, thereby raising the risk of epidemics and increasing the prevalence of diseases such as tuberculosis.25

Livestock, an important supplemental source of income for many farmers, have also been affected by climate change and government inaction. Climate-induced water shortages have caused grass and alfalfa outputs to shrink, resulting in shortages of hay and other fodder that support the raising of sheep, cattle, and other animals.26 As a result, farmers have been forced to sell their herds.27

The consequences of climate change on livestock have been even more severe for Morocco’s already dwindling nomad population, who rely exclusively on animal husbandry for their survival. A 2014 census estimated Morocco’s nomadic population at 25,000, a 60 percent decline from the previous decade, and many scholars project the current population to be as low as 12,000. The government-led process of sedentarization of these pastoralists has been further accelerated, as grazing areas for sheep, goats, and camels become ever sparser due to water shortages. Many desperate nomads have relocated to the outskirts of cities for menial work, such as selling cigarettes or carrying luggage, and are forced to reside in slums with substandard housing.28 As in the case of settled farmers, climate change has also affected social mobility and welfare in these communities: when nomadic heads of household are no longer able to sustain their families, they often pull their children out of school to work and supplement the household’s income.29

Social and religious practices have also been affected by dwindling livestock. According to several specialists, Morocco’s sheep population has decreased to such a degree that many poorer families, in both rural and urban areas, are having to rely on imports for Eid feasts. The Moroccan government is subsidizing the sheep imports, but they remain extraordinarily expensive. “A patriarch will have to work for a month to earn enough money to purchase a sacrifice animal, which was unimaginable ten years ago,” one scholar said.30 Coming to the aid of afflicted nomads, the government is providing significant subsidies for food staples and animal feed and attempting to alleviate water shortages through the dispatch of mobile storage tanks or solar-powered wells. However, the problem of diminishing grasslands persists.

In the Western Sahara, climate-related stresses are inextricably linked with political tensions over the disputed status of this territory. Representatives of the Sahrawi ethnic group and their allies have criticized the Moroccan government for “greenwashing” its activities there, using the extraction of phosphate and expansion of wind farms to centralize and strengthen its control over the region, rather than simply advancing its sustainable energy plans. Sahrawis have also accused officials in Rabat of inflicting the brunt of the Western Sahara’s power and water outages—which they consider intentional and politically motivated—on districts with higher proportions of Indigenous people compared to Arab-dominated cities. Added to this, rights organizations have charged the Moroccan regime with suppressing climate activism in the territory through a range of methods, including refusing to register Sahrawi-led NGOs and arresting and torturing these organizations’ leaders. Strains between the two sides are further exacerbated by the fact that Sahrawi climate activists often couple their environmental work with the cause of self-determination, anathema to the government.

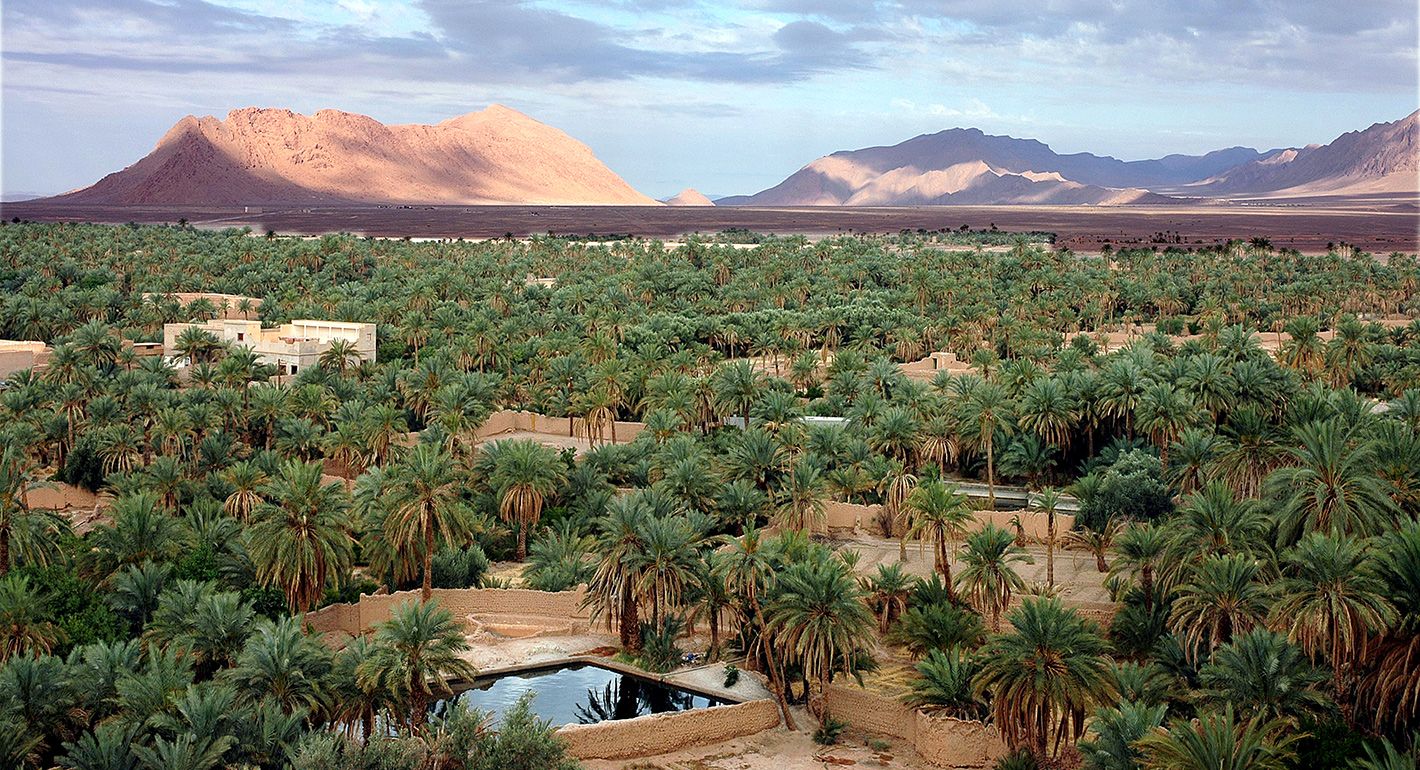

The inhabitants of Morocco’s oases, roughly 2 million people found predominantly in the arid and semi-arid south, represent a uniquely vulnerable category of rural citizens. The climate risks to agriculture and tourism are magnified by the oases’ distinctive and fragile ecosystems and, in some cases, remoteness from government services. Interviewees from such areas pointed to the long-standing ability of oasis farmers, whose crops historically included dates, olives, wheat, barley, maize, alfalfa, pulses, and henna, to adapt to harsh conditions through practices such as the khettara irrigation system. Yet, here again, this traditional resilience is being threatened by the severity of recent climate stresses and by government policies. “The oasis population adapts to drought when it comes to traditional agriculture,” noted Samira Mizbar, a socioeconomist and expert in development dynamics, particularly in oasis and semi-desert areas. When we move to modern intensive agriculture, the problems begin.” 31 To its credit, the Moroccan government has worked to alleviate some of the stressors on those practicing sustainable agriculture through its Green Generation initiative, which has a special focus on youth and women in the agricultural sector. However, this program is pushing against trends driven by climate change and politics, as shown in Figuig and elsewhere.

In Figuig and other oases, farmers shifted from traditional farming to the water-intensive cultivation of dates. These practices began in the 1990s and were accelerated by the 2008 Plan Maroc Vert. These actions, combined with the climate-induced loss of rivers and the evaporation of dams, have caused date yields to fall, pushing greater numbers of Figuig’s 11,000 residents, especially young people, to abandon a centuries-old lifestyle as they move to Moroccan cities or to Europe for work.32 The resulting dislocation has been devastating for many, both financially and psychologically. As noted by one resident:

The drought started over ten years ago. My family lost their land due to desertification about five years ago. . . . We used to grow dates. The palm trees which remained died. This land is my memory. I lived there, I ran there, I played there. I worked there. . . . All this has disappeared. . . . The youth are leaving. The number of inhabitants is diminishing, and the city could eventually disappear with our culture and traditions.33

The Figuig oasis has also emerged as a flashpoint for popular demonstrations against water management policies in Morocco. Starting in late 2023, thousands of residents marched through the town’s streets to protest the municipality’s plan to transition the provision of drinking water from public services to the regional, multiservice agency—a development legitimized by the unpopular Law 83.21. Despite government denials, many Figuig residents saw this transfer of services as a form of privatization that threatened access and affordability at a time of severe drought. Families in the town have been boycotting payment of their water bills since, and leaders of the movement have been drawing expressions of support from civil society groups in Rabat and from demonstrators in Oujda, another water-stressed city in eastern Morocco. Outrage flared further in the town when a leader of the protests was arrested and imprisoned for “contempt of a public official, incitement to misdemeanors and crimes without effect, and contributing to an unauthorised assembly.”

In many respects, the mobilization in Figuig can be seen as an extension of earlier socially motivated protests inspired by the February 20 Movement—the nationwide protest movement born in the wake of the Arab Spring in 2011. According to activists, some of the very same slogans from that movement have been repurposed for water-based demands—underscoring how climate-related stresses can amplify long-standing grievances against misgovernance and poor service provision.34

Interviewees involved in these demonstrations acknowledge that the town is a “special case.”35 Together with water shortages and inadequate service delivery, Figuig has suffered from its geographic location on the Moroccan border with Algeria; for instance, in 1994, the Algerian government closed the border, hurting the livelihoods of farmers from Figuig who for decades had crossed over that frontier to harvest dates. And yet several scientists and activists interviewed for this study also see the town’s mobilization as a potential precursor to future climate-based social movements, including in Morocco’s bigger towns and cities. For now, however, protests in the Figuig oasis have “symbolic value,” the agronomist Mohamed Taher Sraïri asserted, while also warning that “there could be other protests.”36 Echoing this sentiment, a longtime human rights activist who works on climate issues argued, “For the moment, [there are protests] only in Figuig but we could have a problem on a national scale.”37

Finally, Morocco’s Amazigh citizens constitute yet another at-risk population. Comprising an estimated 40 percent of the total population, the Amazigh’s vulnerability as farmers, oasis inhabitants, and nomads is compounded by ethnolinguistic and regional marginalization. Government services to the Amazigh’s historic homeland in the Atlas and Rif Mountains, as with other remote regions, are often uneven. The 2016 anti-government protests that erupted in the city of Al-Hoceïma were motivated in part by substandard services to the Rif region, which has a long history of Amazigh-led resistance and, consequently, more intense government repression than the Atlas Mountains. However, in the Atlas, limited physical access to Amazigh populations complicated Moroccan officials’ efforts to help destroyed villages after the September 2023 earthquakes. That said, the Moroccan government has launched an ambitious reconstruction project for the High Atlas region that, while targeting earthquake-affected infrastructure, may simultaneously remedy some of the more persistent shortcomings.

On a cultural level, climate change threatens Amazigh traditions and livelihoods, with drought and heatwaves—and the government’s massive irrigation schemes—threatening the Amazigh’s sacred and sustainable irrigation system. Relatedly, deforestation has caused the decline of Argan trees and their oil, which is made into a profitable beauty product by Amazigh women. Furthermore, because many Amazigh are engaged in pastoralism, the Amazigh also suffer nomad-specific vulnerabilities, namely reduced groundwater and grass for livestock.

The Amazigh also suffer from government transfers of their land to public entities without prior notice. To construct the Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex, Morocco’s flagship green energy project, the government sold communal Amazigh land to the National Office of Electricity and Drinking Water, which directly transferred it to the publicly funded but privately owned Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy at a price far below market value ($0.10 USD per square meter versus $1–1.20 per square meter). Furthermore, the government promised compensation to afflicted persons via development projects jointly agreed upon by the government and locals, but these projects have not yet begun. Green hydrogen plants, wind farms, and solar farms demand sizeable tracts of land, making land transfers more likely and the consultation of locals all the more necessary as Morocco continues pursuing its National Energy Strategy.

The Amazigh’s vulnerabilities vary by region. In Amazigh communities in the mountains near Marrakech, recent focus groups highlighted the far-reaching, disruptive effects of climate-induced water insecurity, including reduced access to schooling for young girls, sickness, poverty, and unemployment. In the northern Amazigh-majority Rif Mountains, climate-induced stresses are exacerbating lingering grievances related to economic and political marginalization and continued repression stemming from the protests known as the Hirak Rif or Rif Movement from 2016 to 2017. In particular, climate-induced deforestation in the Rif has contributed to soil erosion, increasing the propensity of destructive landslides.

Toward a More Inclusive Climate Adaptation

Morocco has rightly been lauded for its comparative progress in combating climate change and transitioning to renewable energy—the result of a combination of natural resource endowments, geographic location, and foresightful leadership. And yet the full potential of its climate ambitions remains circumscribed by endemic problems of governance, especially in the water management and agricultural sector. Addressing these problems is both a matter of will and capacity, requiring the careful application of technology, regulatory and bureaucratic reforms, and public awareness campaigns. In particular, water and agricultural specialists have underscored the need for a reconsideration and revision of how Morocco manages water. A more sustainable and equitable strategy, they argue, would loosen the grip of the so-called hydraulic lobby on water policies and focus on regulating water demand instead of increasing supply, especially by shifting to crops better suited to the country’s available resources as well as by regulating use by consumers, farmers, and industries alike.38 But, by themselves, these top-down changes are incomplete. What’s needed instead, according to the scientists, activists, and farmers interviewed for this paper, is a more inclusive, bottom-up strategy that directly empowers rural communities to tackle climate adaptation. This new framework would treat vulnerable peoples as partners and agents in that process, rather than victims and subjects; their local knowledge and traditional practices would serve as an adjunct to government policies.

On this front, the role of an independent civil society is paramount. In theory, the Moroccan constitution of 2011, namely Article 12, enshrines the ability of civil society groups in the country to operate freely. And to its credit, the government has encouraged many civil society organizations focused on conservation, awareness, and education, including the High Atlas Foundation, which has collaborated with regional and international partners in reforestation efforts, and Dar Si Hmad, which has introduced fog-catching devices into the Atlas Mountain communities to increase the water supply. Various farming unions are also able to serve as interlocutors between those in the agricultural sector and the government.

However, while Morocco allows for a variety of civil society organizations with climate focuses, the government regularly stifles truly independent voices, especially those with tones of advocacy. Civil society actors that have opposed or directly criticized government policies—especially those emanating from the Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests—have found themselves “ostracized” through de-licensing and other bureaucratic barriers. “If you go their way, you don’t have problems,” noted one activist, “But for more independent groups, the government can make your life more difficult and complicated.”39

Several rights-based climate change groups are perplexed by the government’s confrontational tendencies. Their approach to the government is driven by a spirit of collaboration and cooperation, with a view toward alerting authorities to impending problems on the ground and toward proposing realistic solutions. “We try to anticipate,” said one longtime human rights activist. “We must find answers to the immediate problems, but we are also interested in what could happen [over the long term], and we must alert the public authorities.”40 Simultaneously, these activists are adamant that the protection of citizens’ welfare and vulnerable people’s unconstrained ability to press for better services in the face of climate stresses are inviolable rights, even if they threaten the long-entrenched interests of elites. For many, the threats posed by climate change are so formidable and encompassing—affecting nearly every aspect of citizens’ livelihoods, health, and education—that they demand a similarly holistic response, one in which citizens and government work together as partners.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to their Moroccan interlocutors who shared their views and, in some cases, reviewed drafts of this paper. They also wish to thank Yasmine Zarhloule, a nonresident scholar at Carnegie, and Dina Najjar, a senior gender scientist at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), for their valuable comments.

Notes

1In contrast to petroleum-rich Libya and Algeria, Morocco is highly dependent on energy imports—particularly U.S. coal—to meet its power generation needs and, by one estimation, would deplete its fossil fuel reserves in little more than three days, given its current rate of consumption.

2In tandem, Morocco collaborates with regional and international partners on its green energy projects through forums such as Emerge Green Africa and the African Coalition for Sustainable Energy and Access, thereby facilitating the dissemination and enrichment of Morocco’s green energy innovation research.

3This remarkable achievement is largely due to the construction of Morocco’s Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex, one of the largest concentrated solar farms in the world. Other relevant accomplishments include nationally funded public-private partnerships, especially the Research Institute for Solar Energy and New Energies, which has published hundreds of academic papers on climate adaptation and is creating green technology parks for green energy innovation labs. In addition to debt financing, Morocco’s Central Bank has proactively funded these and other projects through energy taxation and investments in foreign exchange reserves. The UN-managed Green Climate Fund also furthers Morocco’s green finance strategy.

4Ouafae Bouchouata, “Key Climate Challenges and Risks in North Africa,” panel discussion, Carnegie North Africa Conference: Just Energy Transition, Tangier, Morocco, April 22, 2024.

5Waste is another source for alternative, green energy production—in Fez alone, waste is used to power more than 60 percent of energy.

6Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

7Reservoirs are emptying as well, notably the Al Massira dam.

8Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024

9Ibid.

10Interview with Najib Akesbi, Rabat, Morocco, April 24, 2024.

11Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

12Interview with Najib Akesbi, Rabat, Morocco, April 24, 2024.

13Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

14Interview with Najib Akesbi, Rabat, Morocco, April 24, 2024.

15Interview with a Moroccan farmer and unionist, Rabat, Morocco, April 21, 2024.

16Interview with Omar El Hyani, member of Rabat City Council, Rabat, Morocco, April 24, 2024.

17Abderrahim Ksiri, “Climate Governance and Policymaking Challenges in North Africa,” panel discussion, Carnegie North Africa Conference: Just Energy Transition, Tangier, Morocco, April 23, 2024.

18Interview with Omar El Hyani, member of Rabat City Council, Rabat, Morocco, April 24, 2024.

19Interview with a Moroccan activist, Rabat, Morocco, May 6, 2024.

20Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

21Interview with a Moroccan farmer and unionist Rabat, Morocco, April 21, 2024.

22Interview with Siham Rahmoune, Casablanca, Morocco, May 8, 2024.

23Interview with a Moroccan activist, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

24Interview with a Moroccan farmer and unionist, Rabat, Morocco, April 21, 2024.

25Interview with a Moroccan activist, Rabat,Morocco, May 6, 2024.

26Interview with Siham Rahmoune, Casablanca, Morocco, May 8, 2024.

27Ibid.

28Interview with activist and professor Saddik Kabbouri, phone interview, May 10, 2024.

29Ibid.

30Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

31Interview with Samira Mizbar, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

32Ibid.

33Interview with activist Mostafa Brahmi, the brother of the imprisoned Figuig activist Mohamed Brahmi, Casablanca, Morocco, April 27, 2024.

34Interview with Samira Mizbar, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

35Interview with activist Mostafa Brahmi, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

36Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

37Interview with a Moroccan activist, Rabat, Morocco, May 7, 2024.

38Interview with Mohamed Taher Sraïri, Rabat, Morocco, April 20, 2024.

39Interview with a Moroccan farmer and unionist, Rabat, Morocco, April 21, 2024.

40Interview with a Moroccan activist, Rabat, Morocco, May 7, 2024.

.jpg)