Summary

The global democratic recession of the past twenty years has been marked by numerous cases of elected leaders incrementally dismantling democracy through a steady centralization of power and undercutting of checks and balances—what political scientists label as executive aggrandizement. Under the second Donald Trump presidency, the United States is showing clear signs of following such a path, leading many commenters to draw arresting but often relatively glancing comparisons with other prominent recent cases of democratic erosion, like Hungary, India, Poland, and Türkiye. This paper examines U.S. political developments since the return of Trump to power in an in-depth, comparative light, seeking to illuminate the similarities and differences between the unfolding U.S. context and the experience of other troubled democracies.

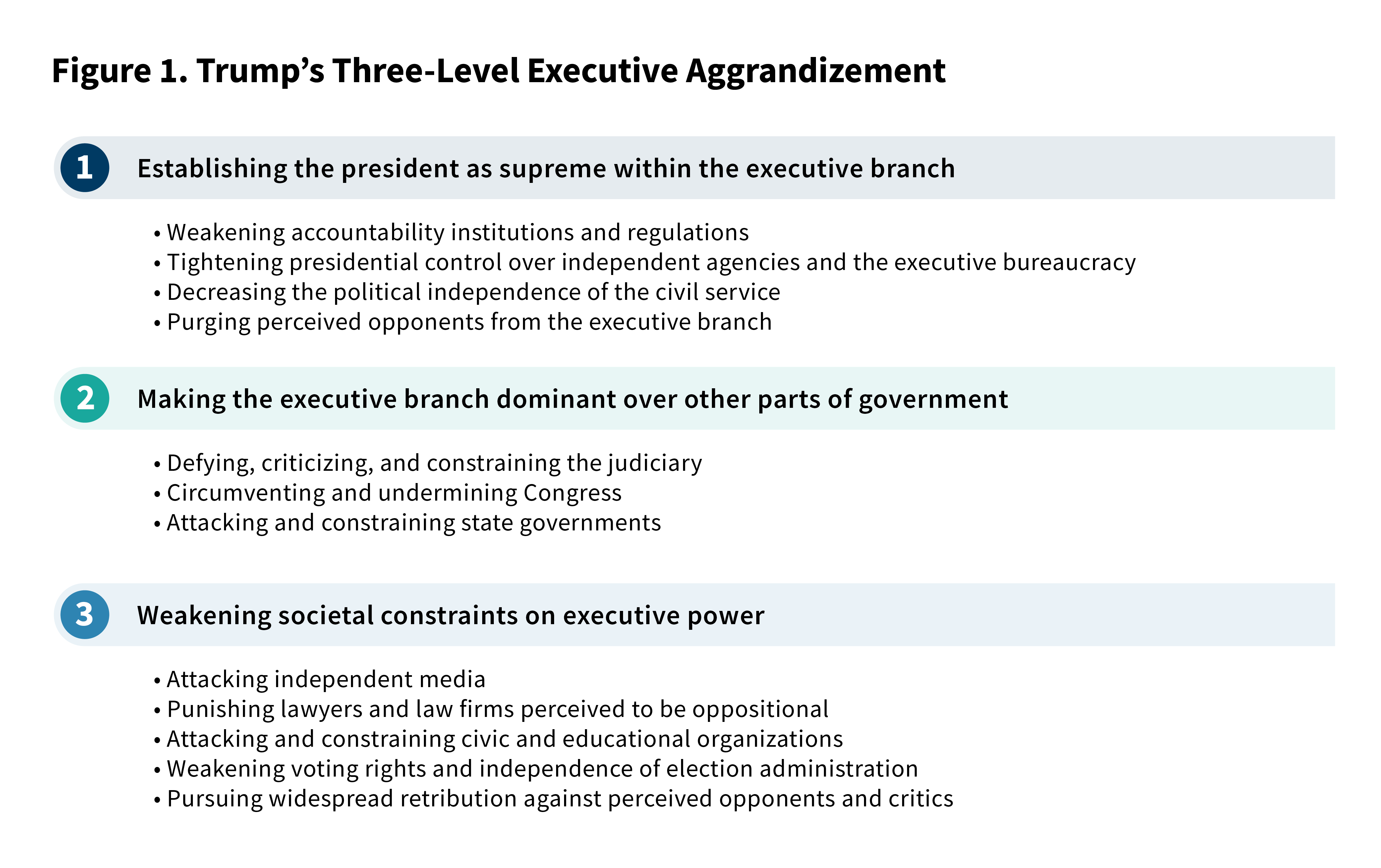

The paper establishes that the Trump administration’s overall political project conforms to the general model of executive aggrandizement, and is best understood as taking place at three interrelated levels:

- Establishing the president as supreme within the executive branch: Trump’s team seeks an extreme form of presidential concentration of power within the executive branch. It has weakened accountability institutions and regulations, tightened presidential control over independent agencies and the executive bureaucracy, decreased the political independence of the civil service, and purged perceived opponents from the branch.

- Making the executive branch dominant over other parts of government: The administration is forcefully seeking dominance over the judiciary, Congress, and states. It has defied court orders, criticized judicial rulings, and constrained individual judges. It has circumvented congressional policies and undermined its powers. And it has attacked and constrained state governments that do not align with administration policies.

- Weakening societal constraints on executive power: Trump has stymied civil society opposition by attacking independent media, punishing lawyers and law firms perceived to be oppositional, and constraining civic and educational organizations. His team has undermined vertical checks on the executive by weakening voting rights and the independence of election administration. Broadly, Trump is pursuing widespread retribution against perceived opponents and critics.

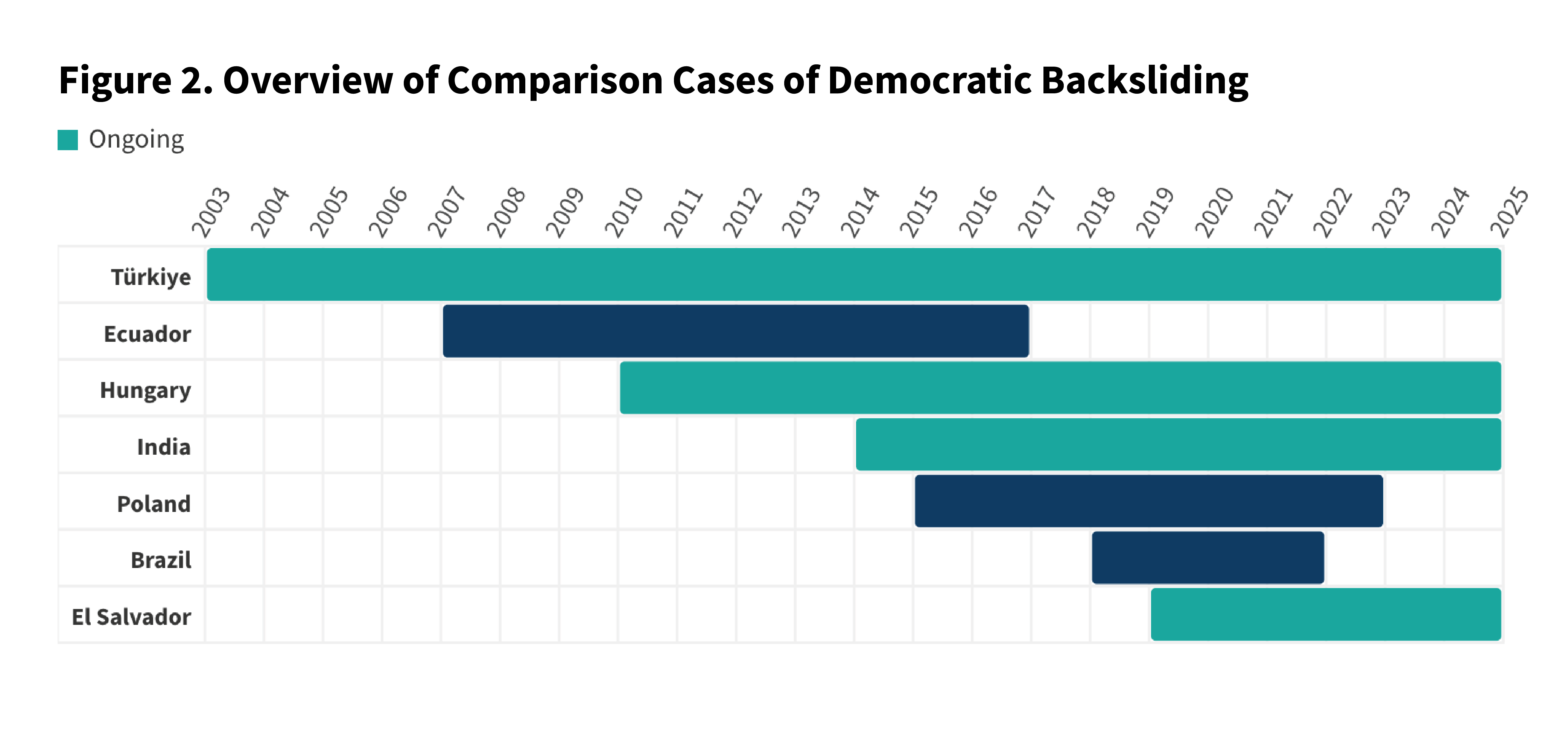

The paper then compares the path of U.S. politics under Trump to seven other recent or ongoing cases of democratic backsliding—Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Hungary, India, Poland, and Türkiye—highlighting distinctive features along three comparative dimensions:

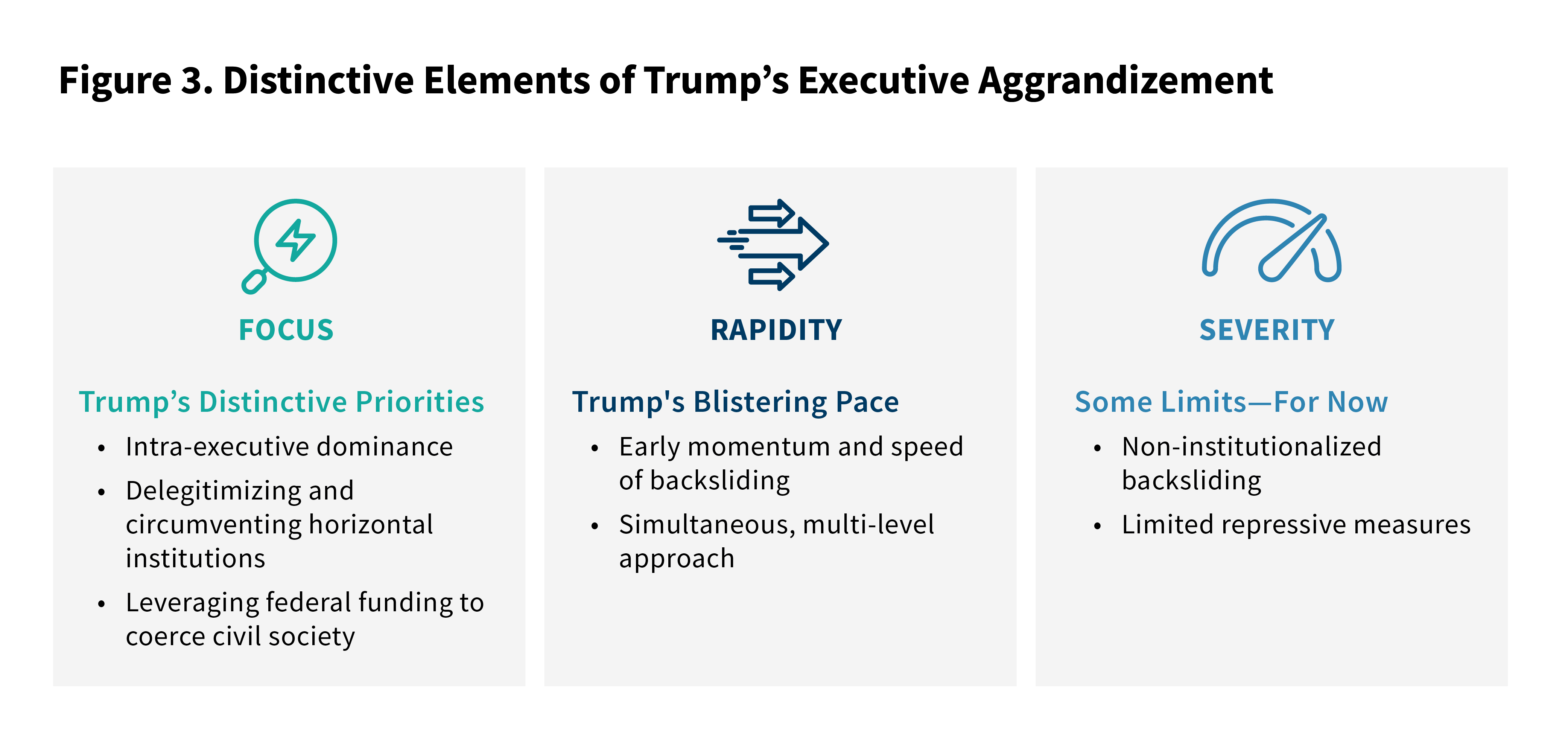

- Focus: The Trump team’s agenda has several priorities that set it apart from other backsliding cases. These include its unique emphasis on intra-executive dominance, delegitimization rather than institutionalized attacks on horizontal checks, and coercive use of the robust federal funding ecosystem to pressure U.S. civil society.

- Rapidity: The administration has carried out its political program with striking speed. Compared to other backsliding cases, it has sought to centralize power with greater momentum and rapidity. And while other leaders often eroded democratic checks piece by piece, Trump’s team is working to weaken such checks across multiple levels all at once.

- Severity: The degree of democratic erosion in the United States is not yet as severe as that of most of its backsliding peers. The country has not yet seen the deep-rooted institutional changes that have characterized many of the comparative cases. And repressive measures like coercive force or criminalization have been limited by U.S. democratic norms and institutions.

While some comfort can be taken from the fact that the relatively deeply rooted U.S. democratic norms and institutions compared to those in the other cases have resulted in a less institutionalized process of backsliding thus far, the distinctive speed and aggressiveness of Trump’s aggrandizement agenda is cause for serious concern. Numerous avenues and sources of resistance to democratic erosion continue to exist, but U.S. democracy is being put to the test as never before in the country’s modern history.

Carnegie Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program

Receive research announcements and invitations to events from the Carnegie Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program.

Introduction

During the past twenty years, the elected leaders of several dozen democracies have taken their countries on illiberal or autocratic paths. This backsliding trend has extended globally—from Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Tunisia to Hungary, India, Poland, Senegal, South Korea, and Türkiye.

When Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, many Americans worried that the United States might suffer a similar political fate. In his first term, Trump questioned and challenged multiple democratic norms and institutions, culminating in his brazen attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election, including his role in encouraging the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. But while shaken by Trump’s presidency, U.S. democratic institutions remained intact.1 Trump left office, and the durability of American democracy was seemingly reaffirmed.

With the return of Trump to the presidency in 2025, however, concerns about the health of U.S. democracy have once again surged.2 Trump and his team have taken a series of actions, from attacking judges who challenge their policies and usurping some basic powers of Congress, to exacting retribution against perceived opponents and seeking to exert political control over universities and other nongovernmental institutions, that have raised serious questions about their commitment to democracy.

Trump and his team have taken a series of actions that have raised serious questions about their commitment to democracy.

Political observers and scholars are debating the severity of this threat to democracy. Some believe that the United States is on the verge of losing its liberal democracy altogether and has already in fact slipped into the category of what political scientists have come to call competitive authoritarian regimes. They argue that checks and balances are actively failing, that the administration is reflexively intolerant of opposition, and that it is openly violating the Constitution and other laws.3 Others are more optimistic. They contend that America’s democratic institutions and federal system, while under serious pressure, are proving largely resilient to autocratic takeover and that U.S. democracy will survive the Trump era.4

Participants in this debate, especially those on the more pessimistic end of the scale, often invoke cases from other countries as evidence for their views. They argue that many of Trump’s actions since January 2025 strongly resemble those by leaders of other countries where democracy has been significantly eroded, that Trump is operating from the same “autocratic playbook” that elected leaders in many other countries have utilized to dismantle democracy.5 Comparisons to democratic erosion in Hungary under Viktor Orbán, in India under Narendra Modi, in Poland under the Law and Justice party, in Türkiye under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and in Brazil under Jair Bolsonaro are especially common. While these and other country comparisons are potentially valuable, they are often injected into U.S. debates in shorthand fashion, like political flashcards rather than in-depth illuminations. This paper seeks to go deeper, to probe the comparative angle on U.S. democratic backsliding in some detail, with a view to providing new insights about the Trump administration’s political project.

The paper proceeds as follows. It first outlines what has emerged globally in the past twenty years as a general model of democratic backsliding: executive aggrandizement—an incremental, executive-led amassing and consolidation of power at the top of a political system that undermines democratic constraints and suffocates democratic freedoms. It then identifies and analyzes the main elements of the Trump administration’s approach. It finds that Trump has pursued three main levels of executive aggrandizement—weakening checks on executive power from within the executive branch, subverting horizontal accountability institutions, and undermining societal constraints on the president.

The paper then brings in the comparative perspective. It examines the U.S. context along three dimensions of executive aggrandizement—focal areas, rapidity, and severity—comparing it to a set of prominent recent or ongoing cases of backsliding in Europe, Latin America, and South Asia. While Trump’s agenda broadly aligns with the common backsliding model, it also diverges in notable ways. Constrained by the institutional guardrails on the president and government that exist within the U.S. democratic system, the administration has focused on subverting, delegitimizing, and coercing the different checks on Trump’s authority rather than seeking the institutionalized democratic erosion more common among backsliding peers. Trump has pursued executive aggrandizement with greater speed and aggression than most other backsliding leaders, yet U.S. democratic erosion is not, at least so far, as severe as in a number of other backsliding cases.

While the continued resilience of U.S. democracy to date may offer some reassurance, the fact that backsliding in the United States has come this far so fast signals the seriousness and urgency of the ongoing threat to democracy. It remains unclear how much further the Trump administration will go with its executive aggrandizement in the next few years, but understanding the U.S. case in global context provides useful perspective about what may lie ahead.

The Common Backsliding Model

Comparative studies of the ongoing global trend of democratic backsliding highlight a high degree of similarity in the basic political method at work—what analysts label as executive aggrandizement or executive overreach.6 Employing this method, elected leaders with antidemocratic intent amass a preponderance of power by undermining all major constraints on their power, whether in the form of horizontal or vertical lines of accountability. Common tactics include weakening the independent judiciary and legislature, politicizing and weaponizing prosecutorial power, undermining the fairness of the electoral process, censoring or harassing independent media, co-opting private businesses, and undercutting the independence of civil society. Executive aggrandizement contrasts with forms of democratic erosion that used to dominate cases of backsliding, such as military coups, or other forms of abrupt, authoritarian takeovers.7 It involves leaders who have been fairly elected acting incrementally, wielding existing political processes and institutions to erode democratic norms and structures step by step, usually while characterizing their actions as reforms needed to strengthen or purify democracy.

Despite the strong commonalities of this model across most of the main cases of democratic backsliding in recent years, variations exist along at least three axes.8 First, backsliding leaders differ in the specific institutions and sectors they target. Often, their approach is shaped by underlying features of the domestic context, such as the configuration and rootedness of existing institutions—like whether it is a parliamentary or presidential system—or elements of political tradition and culture. It may also be influenced by contingent features of the context, such as whether the leader has a legislative majority, a well-established party, and particular political skills and inclinations. Second, the pace at which executive aggrandizement proceeds varies. In some cases, leaders move only very gradually, taking years to implement a wide-ranging set of aggrandizing actions, while in others, leaders move much more quickly. Third, the breadth and depth of aggrandizement and its damage differ widely. In some countries, executive aggrandizement has gone so far as to move the country fully away from democracy. In others, it is relatively limited, hurting democratic norms and institutions, but not debilitating the democratic system overall.

Trump’s Three-Level Executive Aggrandizement

During its first seven months, the Trump administration’s policies, statements, and actions comprise a clear attempt at executive aggrandizement. As set out in Figure 1, this effort operates on three interrelated levels—establishing the president as supreme within the executive branch, making the executive branch dominant over other parts of government, and weakening societal constraints on executive power.

Level 1: Establishing the President as Supreme Within the Executive Branch

The Trump administration is pursuing a sweeping effort to elevate the president within the executive. Building on theories once considered at the fringe of legal thought, it is asserting a vision for the presidency in which the president reigns supreme over all parts of the executive branch, with even formally independent executive agencies and employees transformed into vehicles for his will. A trend toward greater presidential authority has been growing in U.S. politics, across successive administrations from both parties, for some time. But the current administration is pursuing a much more extreme form of executive concentration of power, one that conforms to what is known as the “unitary executive theory”—which argues that the U.S. Constitution endows the president with total control essentially over the entire executive branch, including positions such as inspectors general and independent agency commissioners.9 In pursuit of this vision, the administration has:

- Weakened accountability institutions and regulations;

- Tightened presidential control over independent agencies and the executive bureaucracy;

- Decreased the political independence of the civil service; and

- Purged perceived opponents from the executive branch.

An early focus of the Trump team was undercutting institutionalized checks on the administration that might come from within the executive branch. Shortly after assuming office, Trump dismissed seventeen inspectors general from executive agencies, replacing them with political loyalists.10 In February, he fired the head of the Office of Special Counsel and the director of the Office of Government Ethics, independent agencies tasked with protecting federal whistleblowers and monitoring executive ethics rules compliance.11 He reduced internal constraints on executive activities, such as rescinding ethics rules from the Joe Biden administration that prevented executive branch employees from taking major gifts from lobbyists.12 He has undermined the independence of executive branch prosecutors, weakening institutional protections for them, launching a Justice Department “Weaponization Working Group” to probe their activities, and taking retributive actions against some prosecutors who criticized or had participated in investigations into Trump.13 His administration has also targeted officials within traditionally independent agencies across the executive who could check or question presidential prerogatives, including firing members of the National Labor Relations Board and the Federal Trade Commission.14 And in late February, Trump signed an executive order that subjects independent executive agencies to greater oversight and regulation by his administration.15

The Trump team has paired this effort to tighten political control over executive agencies with acts that politicize the executive workforce more broadly. It reduced protections for federal workers, making it easier for the administration to fire them at will.16 It has implemented measures that politicize the federal hiring process—like Trump’s February executive order which mandated that the State Department strictly align its recruitment with the administration’s political beliefs.17 Trump granted several allies and friends “special government employee” status, which has vested them with influence over various agencies while shielding them from federal conflict of interest restrictions.18 He has taken retributive actions against executive branch officials merely for carrying out their duties when such actions do not align with his own priorities, such as firing the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics in August when the bureau released a job report with weak numbers.19 And across multiple agencies, Trump has removed or demoted dozens of the officials who participated in investigations into events that occurred during his first term.20

The balance of power within the executive has already shifted markedly toward absolute presidential authority as democratic safeguards within the executive branch are purged or co-opted.

How much the administration intends to weaken executive agencies is unclear. But the balance of power within the executive has already shifted markedly toward absolute presidential authority as democratic safeguards within the executive branch are purged or co-opted.

Level 2: Making the Executive Branch Dominant Over Other Parts of Government

The second level of Trump’s executive aggrandizement is his effort to assert dominance over other parts of the government that traditionally have served as checks and balances on the executive. To this end, Trump and his team have:

- Defied, criticized, and constrained the judiciary;

- Circumvented and undermined Congress; and

- Attacked and constrained state governments.

Trump and his team are challenging and questioning judicial authority more than any U.S. administration in modern history.21 At its most extreme, their attacks on the judiciary have involved outright defiance of court rulings. As judges have issued rulings to curtail the administration’s behavior in recent months—such as a February order which mandated that the government release federal grant funds, an order in March which forbade the administration from deporting a group of Venezuelan migrants, and an April order which ordered the government to fund a program that provided legal representation to minors who are alone at the border—the Trump team has repeatedly disobeyed the directives, denying their validity, interpreting their mandates in narrow ways, or delaying their implementation.22 By July, the Trump administration had been accused of “flouting courts in a third of the more than 160 lawsuits against the administration in which a judge has issued a substantive ruling.”23

Trump and his allies have also undermined the authority of the judiciary in the public’s eyes. They have launched repeated verbal attacks against individual judges who have ruled against Trump’s agenda. The White House called rulings “absurd and judicial overreach”; the president claimed that judges “should be IMPEACHED”; the attorney general complained when an “unelected federal judge” “yet again invaded the policy-making and free speech prerogatives of the executive branch”; and the vice president suggested that “judges aren’t allowed to control the executive’s legitimate power” at all.24 The president and his team have paired these attacks with efforts to constrain judges. In mid-March, the administration attempted to disqualify Judge Beryl A. Howell from overseeing a lawsuit brought against the administration by a law firm that it had targeted.25 In July, the Justice Department filed a misconduct complaint against Judge James Boasberg, in which it alleged that he had made “improper public comments” about Trump and called for his removal from a case against Trump’s deportations.26 In recent months, violent anonymous threats against federal judges who ruled against the Trump administration have reached unprecedented highs, contributing to a rising fear among judges that they and their families will be at risk if they challenge the administration.27

Trump’s relationship with Congress has been less overtly antagonistic than that with the judiciary—reflecting the general acquiescence of the Republicans in the House and Senate to the administration’s assertions of power.28 Trump’s team has at times targeted members of the Democratic opposition with rhetorical attacks or investigations—like former interim U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia Ed Martin’s “Operation Whirlwind,” which involved Martin sending intimidating letters of inquiry to Democratic representatives under the guise of investigating threats against public officials.29

More generally, Congress is allowing the Trump administration to sideline its authority. For example, the administration has repeatedly bypassed congressional impoundment authority—the “power of the purse.” Trump and his allies have long argued that this authority was unjustly stripped from the president by the 1974 Impoundment Control Act.30 Now, the administration is reasserting executive control over federal funds. On one level, it has withheld existing congressionally allocated money. In January, the Trump team blocked funding that had already been appropriated by Congress when it issued a sweeping pause on all disbursement of federal financial assistance. Blocking such funding is also often one of the first steps that the Trump team takes in the process of gutting congressionally established agencies, like it did at the U.S. Agency for International Development.31 The Government Accountability Office has determined that the administration has violated the Impoundment Control Act three times—when the administration withheld funding for the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program in February, to the Institute of Museum and Library Services in April, and to the Head Start preschool program since January.32

Simultaneously, the administration has unilaterally reallocated federal funding, circumventing congressional pathways to do so. For example, Trump employed the National Emergencies Act to channel money to his militarization of the border without congressional authorization. And it has sought to coerce Congress on funding issues, such as in June when Office of Management and Budget Director Russell T. Vought threatened the use of a “pocket rescission” to cut spending by overriding congressional authority if legislators did not acquiesce to the administration’s budgetary demands.33

Congress has also been permissive of the administration’s broader use of executive orders and actions to skirt congressional policymaking authority. For example, Trump signed an order in January to suspend the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, though it had been established in a statute by Congress.34 He invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to justify his imposition of tariffs in April, sidestepping U.S. trade law processes despite IEEPA being intended for national security scenarios, particularly wartime.35 In March, Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport alleged members of a Venezuelan gang without hearings—another wartime executive privilege, even though Congress had not declared a state of war, and in disregard for the role of legislation in regulating immigration issues.36

Trump’s administration has also exerted executive authority over issues that traditionally fall within the purview of state authority. It has tried to pressure state actors into acquiescing to Trump’s policy agenda, such as when it threatened to withhold federal funds for sanctuary cities.37 It froze federal funds to Maine after Governor Janet Mills refused to cede to the government’s demands that the state change its policies on transgender athletes.38 In April, Trump issued an executive order on U.S. energy policy. In it, he accused state governments of “overreach” that has hindered American energy dominance and tasked the attorney general with taking “all appropriate action to stop the enforcement of State laws” that the administration determines to be illegal, a criterion based in large part on whether state laws clash with the White House’s objectives and policies.39 And in some cases the administration has sidestepped state authorities altogether, such as in early June when Trump ordered the deployment of California’s National Guard in response to protests in Los Angeles, against California Governor Gavin Newsom’s wishes.40

Level 3: Weakening Societal Constraints on Executive Power

The third level of the Trump administration’s executive aggrandizement has been its concerted effort to stymie societal opposition and weaken vertical checks on the executive. It has sought to constrain fundamental pillars of a democratic society by:

- Attacking independent media;

- Punishing lawyers and law firms perceived to be oppositional;

- Attacking and constraining civic and educational organizations;

- Weakening voting rights and independence of election administration; and

- Pursuing widespread retribution against perceived opponents and critics.

Trump and his team have weakened the press by verbally attacking individual journalists and targeting media companies with lawsuits and investigations.41 His administration has excluded certain media organizations from governmental spaces in retaliation for disliked actions by or outlooks of those organizations—including banning the Associated Press from White House events and amending the press pool process to hand-pick which outlets are allowed to attend. It filed lawsuits against media organizations like ABC News, CBS, and the Des Moines Register; launched Federal Communications Commission investigations into NPR, PBS, and Comcast; and asked Congress in June to rescind over $1.1 billion for the nonprofit Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which supports local radio and television stations, forcing it to begin shutting down by August.42 In July, Trump sued the Wall Street Journal for publishing a story he did not like relating to his past friendship with Jeffrey Epstein—the first time in U.S. history that a sitting president has sued a media organization for alleged defamation.43 Trump’s propensity to retaliate against critical media coverage stifles dissent and reduces the ability of the press to act as a watchdog within U.S. democracy.

The administration has disempowered independent organizations within U.S. society that might constrain the president. Law firms were an early target. In March and April, Trump signed several executive orders that restricted the business activities and federal access of law firms that had current or former members who had participated in cases against Trump and his allies. As these orders multiplied, they had a chilling effect on other firms, several of whom signed preemptive agreements with the administration to avoid the planned penalties.44

The administration has also targeted sites of perceived ideological opposition—like nonprofits and universities. In March, Trump issued an executive order to restrict public service loan forgiveness to organizations with an “illegal purpose”—a change meant to constrain so-called “activist organizations,” and which threatened the tax-exempt status of some nonprofit organizations.45 Since January, there have already been at least thirty-two Republican-led congressional investigations into nonprofits, compared to forty-three investigations during the entirety of the previous Congress.46 While Trump and his allies have not yet enshrined their efforts to weaken dissent in repressive, whole-of-society laws or outright co-option of independent organizations, their attacks on these sectors reflect a willingness to strike out against perceived ideological disagreement.

More broadly, Trump’s team has sought to chill anti-government protests through the militarization of responses to protests and the demonization of societal mobilization. Amid June protests in Los Angeles against the administration’s policies toward immigrants, Trump deployed the National Guard and U.S. Marines to California.47 Trump personally threatened to deport protestors, stating: “One thing I do is, any student that protests, I throw them out of the country.”48 When counter protests were organized in response to Trump’s Washington, DC, military parade in June, he warned that they would be met with “heavy force.”49 And though the federal government has not restricted the public’s right to assemble peacefully, laws to penalize protests have been emerging in recent years from ideologically-aligned state governments.50 The Trump team has capitalized upon these local attacks on societal mobilization in its efforts to paint dissent as criminal.51

Finally, the administration is systematically weakening a core avenue for vertical constraint: electoral institutions. Since his re-election, Trump has continued to call into question the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election, supporting the January 6 insurrectionists and downplaying the anti-democratic nature of their assault on the Capitol. He pardoned the rioters, claiming that their prosecution was “a grave national injustice.”52 And his team has targeted officials involved in the January 6 cases, including firing over a dozen prosecutors, launching investigations into the activities of others, and demanding information about FBI workers who had worked on the cases.53 Trump continues to spread false claims about the 2020 presidential election itself, including in social media posts like those from June in which he raged that “Biden was grossly incompetent, and the 2020 election was a total FRAUD!”54 He has publicly hinted at running for a third term, claiming that there are “methods” that would allow him to subvert the constitutional two-term limit on U.S. presidents.55

In parallel, the administration is asserting authority over state-run elections and weakening voting rights and election protections. In March, Trump issued an executive order requiring proof of citizenship to vote, directing the Department of Homeland Security to review each state’s voter registration lists, and mandating that changes be made to state-level mail-in ballot practices.56 At his urging, Texas Republicans are attempting to redraw congressional districts to switch five Democrat-held districts to the Republican Party.57 The Department of Justice has accused states of failing to maintain verified voter rolls, and it has demanded voter registration lists and other election records from at least fifteen states.58 It has dropped every voting case that the government was a plaintiff in before the administration began and ended electoral racial discrimination investigations in several states.59 Nationally, Trump’s team is weakening election infrastructure and protections—such as disbanding the Foreign Influence Task Force that safeguarded elections from foreign intelligence operations and reducing the independence of the Federal Election Commission.60

Broadly, Trump’s continuous rhetoric labeling people who disagree with him or who pursue alternative political agendas “evil,” “enemies,” “criminals,” and “lunatics” and his repeated efforts to back some of that rhetoric with tangible punishment has created a climate of political fear unprecedented in modern American history. As one observer recently wrote, “Fear is the universal tool of authoritarians, and it is a clear sign that our democracy is in danger that so many Americans now have reason to fear their government.”61

The administration is curtailing the basic forms of bottom-up political accountability that are fundamental to a democratic system.

Together, these three levels of action by Trump and his administration constitute an integrated, systematic attempt at executive aggrandizement. The administration’s elimination of executive constraints on presidential power and assertions of dominance over the judicial and legislative branches, as well as state governments, are weakening the core institutions and norms of legal and political accountability essential for democratic governance. And by undermining societal opposition and vertical checks on presidential power, the administration is curtailing the basic forms of bottom-up political accountability that are also fundamental to a democratic system.

Comparing to Other Cases

How does Trump’s political project compare to the processes of backsliding that have played out in other countries in recent years? A common refrain from political observers is that the Trump administration is following the same pathway set out by leaders in countries like Brazil, Hungary, India, and Türkiye. They worry that the similarities signal that the United States will soon find itself in the same straits as these badly damaged democracies. Certainly, there are important, troubling similarities of both means and goals. Yet there are also differences between the Trump administration’s approach and the executive aggrandizement that has occurred elsewhere. Shedding light on these distinctive elements helps paint a fully nuanced picture of the current state of U.S. democratic backsliding.

In pursuit of such illumination, this study compares the United States under Trump to seven recent or ongoing cases of democratic backsliding: Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Hungary, India, Poland, and Türkiye. Figure 2 sets out some basic facts regarding the relevant democratic erosion in these countries. While these do not represent the full range of available cases, they include commonly invoked cases that in their different ways share several important features with the U.S. context. Hungary and Poland are high-income democracies with strong ties to the community of other high-income democratic states. Türkiye, while middle income, experienced notable economic dynamism for most of this century. Brazil, Ecuador, and El Salvador feature presidential systems where elected leaders sought to amass dominant presidential power. In India, executive aggrandizement has taken place within a vast, complex federal structure that oversees a large and diverse society. All of these countries have experienced deepening political polarization, which illiberal leaders have magnified and leveraged in their efforts to expand executive authority.

In analyzing the United States in relation to these other backsliding cases, this study zeros in on three comparative dimensions of the different processes of executive aggrandizement—focus, rapidity, and severity. Compared to other backsliding cases, it finds that the Trump team has placed a particular emphasis on dominating the executive branch, on delegitimizing horizontal institutions, and on coercing civil society through funding cuts and regulatory pathways. Trump and his team have attacked checks on the executive with unusual speed and aggression. But with regard to severity, U.S. democratic backsliding is not yet as institutionalized or repressive as in some of the other prominent cases. These findings within each of the three dimensions are briefly summarized in Figure 3.

Focus: Trump’s Distinctive Priorities

Across different backsliding cases, leaders often prioritize particular focal areas of aggrandizement. In comparison to the other backsliding cases in this study, the Trump administration’s focus on three areas stands out: on intra-executive dominance, on delegitimization and circumvention as strategies to weaken horizontal institutions, and on weaponization of federal funding as a coercive and retributive tool. While other leaders have employed these tactics to varying degrees, the Trump administration is unusual in the extent to which it has prioritized each. This distinctiveness sheds light on the elements of U.S. democracy that have constrained or influenced Trump’s agenda—including the dynamics of its presidential system and the checks on constitutional and institutional change within it.

Intra-executive Dominance

In comparison to other backsliding countries, the Trump administration’s approach is uniquely centered on restructuring and dominating the executive branch. Why in the United States and not elsewhere? In the other cases, backsliding leaders faced fewer barriers to gaining consolidated control over the executive from the outset—allowing many aggrandizing leaders to focus fully on targeting legislatures, courts, or civil society. In the United States, Trump operates within a highly (at least until recently) rule-bound executive branch. Internal checks limit presidential overreach from within, and structural constraints make co-opting the legislature or judiciary deeply challenging. As a result, emphasizing intra-executive dominance is a more feasible pathway to early aggrandizement in the United States.

From the outset of his tenure, Trump directed his energies toward consolidating control over the branch—purging oversight institutions, politicizing civil service processes, bringing independent agencies under its control, and reducing overall federal bureaucratic capacity. In isolation, the individual tactics that the Trump administration has employed are not unprecedented among backsliding leaders. In cases from Brazil to India to Türkiye, leaders also co-opted oversight agencies and politicized the government workforce. But in such cases, these efforts tended to be a secondary focus within their broader aggrandizement agenda. Their political systems often made it unnecessary or less important to consolidate executive branch control. Instead, the judiciary, legislature, or civil society were the main early focuses as leaders sought to expand their power.

This was true in several cases with parliamentary systems, like Hungary and Poland, where horizontal institutions were the first major targets of aggrandizement efforts. In these cases, party dominance within the legislature vested the new leadership with power over their executive apparatuses. In Hungary, Orbán’s Fidesz party won 68 percent of the parliamentary seats in the 2010 elections.62 As prime minister with a legislative supermajority, Orbán was then empowered to pass constitutional changes that he used to eliminate judicial checks from the Constitutional Court as he pursued his power grab. Similarly, after the Law and Justice (PiS) party came to power in Poland following the 2015 parliamentary elections, the party leveraged its unified executive-legislative control to target horizontal institutions, quickly launching a series of structural changes that undermined the independence of the judiciary.63

But even among the comparative cases with presidential systems, it is unusual for newly elected leadership to place such emphasis on internal domination of the executive branch. In part, this may be due to a greater presumption in other countries that the executive branch is an extension of presidential will. Consider Rafael Correa’s approach after he assumed the presidency of Ecuador in 2007. Unlike Trump’s ongoing efforts to reshape the executive branch, cutting agencies and firing staff to ensure internal alignment with the administration’s agenda, Correa expanded the executive bureaucracy significantly during his time as president, doubling the number of ministries in his cabinet over a ten-year period.64 But even this wasn’t the immediate priority in his aggrandizement agenda—his major focus early on was constraining horizontal democratic institutions. For example, one of his first moves in power was to push for a constituent assembly to bypass Ecuador’s existing legislature, gaining control over the policymaking process and undermining the legislature’s capacity to function as a check on the president.

Brazil and India present cases that are in many ways more similar to the U.S. context. When Jair Bolsonaro came to power in Brazil in 2019, he took several measures to politicize the executive branch through the appointment of many military officials and political loyalists to positions within it. But dominating the executive was a lower priority for Bolsonaro than it has been for Trump. Brazil’s system was already characterized by weak executive oversight institutions, and Bolsonaro did not go as far as Trump has already done to fundamentally reshape the executive branch’s internal structure and institutions.65 Similarly, in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) targeted internal watchdog institutions, extensively restructured ministries to align with Modi’s agenda, and consolidated power in the Prime Minister’s Office. But Modi’s legislative majority in India’s parliamentary system gave him alternate political pathways that he has since prioritized in his efforts to target horizontal and civil society dissent.66

Trump’s approach to the executive branch is more pronounced than those of these other leaders. Amid the constraints and guardrails of the U.S. democratic system, he has relied heavily on executive actions and pathways to enact his agenda. And his concerted effort to dominate the executive branch through extensive restructuring and purging has been a major focus of the early months of his presidency.

Delegitimizing and Circumventing Horizontal Institutions

The Trump administration’s approach to weakening horizontal checks is a second distinctive element. Constrained by institutional guardrails that make it difficult to pass constitutional amendments or structurally disempower the courts and legislature, the Trump team has focused on other ways of undercutting the horizontal institutions that stand in its way. Compared to the institutionalized changes that leaders have pursued in other backsliding cases, Trump’s approach has focused much more on normative democratic erosion and the overreach of presidential powers.

To undermine the judiciary, for example, the administration has systematically sought—as described above—to discredit the courts rather than pursue structural changes. The administration has not made the U.S. Supreme Court a direct target—given that it leans strongly conservative and is a well-established institution within American democracy, it is a low-reward, high-cost institution for Trump to attack. But the administration has challenged the legitimacy of judicial constraints on the executive broadly, and ignored, attacked, and avoided full or timely implementation of judicial rulings against it.

Trump’s approach is markedly different than the constitutional amendments or legislative measures that leaders in other countries have used to structurally weaken the courts. For example, the PiS enacted deep institutional changes to the Polish judiciary. There, while the government also heavily criticized the judiciary, it paired these attacks with legal changes that brought the Polish court system under party control. PiS legislators vested the administration with the authority to determine appointments to the Polish National Council of the Judiciary and lowered the retirement age for Supreme Court justices to enable PiS to pack the court with party loyalists. They passed legal measures that reduced the powers of the Constitutional Tribunal and changed the regulations governing the Supreme Court to further diminish its independence.

In El Salvador, too, when President Nayib Bukele’s party won a legislative supermajority in 2021, he led a series of legal changes to bring the judiciary under executive control. His party-held legislature removed every justice from the country’s constitutional court, installing its own replacements. It passed laws that enabled the administration to remove judges above a certain age and that gave Bukele greater control over the terms of judges.67 Institutionalized control over the judiciary has subsequently aided Bukele’s effort to expand his executive control, for example through a Constitutional Court decision allowing Bukele to circumvent term limits. Like in Poland and El Salvador, structural changes to the judiciary also took place in Ecuador, Hungary, and Türkiye.

While most of the comparative cases involved some degree of institutionalized attacks on the independence and strength of judiciaries, some other backsliding leaders have, like Trump, also tried to delegitimize the judiciary. Most notably, Bolsonaro’s attacks on Brazil’s Supreme Court were strikingly similar to the rhetoric currently coming out of the Trump administration. Amid investigations into Bolsonaro’s illiberal actions, Bolsonaro repeatedly claimed the court was overreaching, threatened to impeach justices, and even suggested that he would not adhere to unfavorable court decisions.68 In India, while Modi’s government has not succeeded in exerting formal control over the judiciary, it has leveraged regulatory processes to undermine oppositional judges and boost loyalists, creating a culture of judicial self-abrogation.69

Judicial delegitimization also can precede efforts at institutional change. In Türkiye, for example, Erdoğan clashed with the judiciary relatively early on in his tenure, highlighting issues that were broadly popular with Turkish society to erode public support for the courts. But he then capitalized upon this discontent to justify his institutional weakening of the judicial system and expansion of executive power through constitutional changes in 2010.70 Though there are clear early parallels between Erdoğan’s and Trump’s tactics, it remains to be seen if the Trump administration’s emphasis on judicial delegitimization will evolve into similar attempts to structurally change the judiciary, or if—like in Brazil—Trump’s erosion of judicial authority will remain mostly in the form of vituperations and disobedience.

The Trump administration’s approach to Congress—often subverting or circumventing it rather than co-opting or enlisting it—is also distinctive compared to other executive aggrandizement cases. In other cases, the executive and legislature have worked in tandem to weaken democratic checks and expand executive power through legislative means. In parliamentary systems like Hungary and Poland, where executives are selected by and beholden to their legislative majority, the legislature is a natural pathway for the leadership’s backsliding agenda. In Poland, for example, the PiS-led parliament and former president Andrzej Duda systematically eroded the independence of the judiciary and civil society through extensive legislative changes.

Even compared to other presidential cases, the Trump administration has still placed a greater emphasis than other leaders on subverting rather than co-opting the legislature. While other presidents also employ executive powers to enact their aggrandizement projects, such leaders often do so in lockstep with their legislatures. For instance, in El Salvador, even though Bukele has deployed a state of emergency to consolidate control over much of civil society, he has also made extensive use of legislative pathways in his efforts—such as when he leveraged his majority in the Legislative Assembly to enact changes that weakened the judiciary at the outset of his backsliding drive, or in August 2025, when the legislature approved amendments to the constitution that abolished presidential term limits.71 While Ecuador’s Correa used his popular support to take over the legislature through a constitutional referendum, his administration subsequently worked with this new, loyal legislature to pass restrictions on investigative institutions and civil society freedoms.72

The Trump administration has relied predominantly on executive orders, states of emergency, funding threats and cut-offs, and rhetorical tactics to achieve its executive aggrandizement ends, with little energy spent on legislative pathways.

By contrast, the Trump administration has relied predominantly on executive orders, states of emergency, funding threats and cut-offs, and rhetorical tactics to achieve its executive aggrandizement ends, with little energy spent on legislative pathways. In part, this reflects Trump’s narrow legislative majority and the constraints of the U.S. system. The slim Republican majorities in the House and Senate do not give Trump and his allies the unfettered capacity to enact nationwide changes at speed and scale. A complex, bicameral legislative process with a filibuster makes legislation a challenging avenue for change, while state governance and the federal system provide another check on legislative influence. In many ways, Congress is simply a less effective avenue than others through which Trump can carry out his aggrandizement agenda. And using executive orders and emergency powers to enact policy serves Trump’s aggrandizement goals. Constitutional change is notoriously difficult in the United States, making the constitutional restructuring of legislatures that took place in cases like Ecuador, Hungary, and Türkiye practically unfeasible for Trump. But by circumventing legislative authority repeatedly, Trump’s administration continues to set new precedents for presidential authority that shift the normative baseline of control over policy issues in Trump’s favor.

Leveraging Federal Funding to Coerce Civil Society

A third distinctive focal point of Trump’s aggrandizement agenda is his use of federal funding to intimidate and constrain U.S. civil society. In itself, this is not unusual among backsliding leaders. Cutting off resources for independent societal organizations is a common tactic within the executive aggrandizement model. But two features of the U.S. context stand out. First, few governments oversee funding channels as expansive as those that exist within the United States, and few countries contain civil society ecosystems as large and institutionally embedded. This makes federal funding a particularly impactful coercive tool for the Trump administration. Second, unlike leaders in most of the comparative backsliding cases, Trump has not yet imposed sweeping legal repression of civil society. Legal and normative guardrails make this a challenging pathway in the United States. But it is notable that the administration has made such aggressive use of the funding and regulatory tools that are available to it to weaken oppositional civil society and punish organizations that refuse to comply with its demands.

Other backsliding leaders have also focused on funding mechanisms as levers to exert control over civil society groups. In Poland, for example, the conservative PiS government cracked down on government funding for nongovernmental organizations, particularly for LGBTQ and women’s advocacy groups.73 Similarly, in each of the other comparative cases, illiberal governments restricted funding for domestic civil society groups.

In several of these cases, however, restrictions on foreign funding were a more important tool as governments sought to stifle civil society opposition. In India, for example, Modi made use of repressive laws to block domestic nongovernmental organizations from receiving foreign funding and limited the activities of those organizations that did receive external funds, significantly constraining India’s independent civil society.74 In El Salvador, the Legislative Assembly approved a “foreign agents” law in May 2025 that granted the government extensive control over civil society entities that receive foreign funding, and which has raised widespread concerns about its coercive nature.75 Unlike such cases, in which illiberal leadership could seriously constrain independent civil society by cutting off foreign funding, U.S. civil society has not traditionally been very reliant on external sources. Its domestic funding ecosystem is robust, and its institutions have long received significant support from different federal funding pathways. Now, it is this same financing system that the Trump team has co-opted in its efforts to repress domestic dissent.

The speed and intensity with which the Trump administration has wielded federal funds to weaken civil society is also notable. On the one hand, unlike in comparative cases, the Trump team has not yet paired funding cuts with more expansive legal constraints on societal freedoms. Its tactics have primarily focused on the existing points of leverage it has over civil society. For example, Trump has used federal funding to try to coerce universities to align with the administration’s values.76 At Harvard, the administration demanded that the university change its internal governance structure and eliminate diversity, equity, and inclusion provisions. When Harvard refused to acquiesce to these demands, the government responded by freezing the university’s federal funds and trying to revoke Harvard’s tax-exempt status, alongside other regulatory tactics like restricting visas for international students.77 Elements of this attack were similar to efforts undertaken by Orbán in Hungary, who spearheaded legislation to dismantle the foreign-funded Central European University in 2017, although Orbán’s assault focused on legal coercion rather than financial weakening. 78

It might seem comforting that the administration’s assault on civil society has prioritized tactics like financial coercion rather than more deep, repressive institutionalization. On one hand, this is a testament to the U.S. democratic system—legal restrictions on independent institutions may simply be more challenging for the Trump administration in the face of American norms, rule of law, and democratic checks. But on the other, Trump’s weaponization of federal funding to target entities like Harvard is striking in its intensity and scope, which has been anomalous within the U.S. context. It sheds light on the willingness of the administration to fully leverage the tools at its disposal to constrain civil society, reflecting an animosity toward independent civil society that parallels repressive backsliding governments around the world.

Trump’s weaponization of federal funding to target entities like Harvard is striking in its intensity and scope, which has been anomalous within the U.S. context.

Rapidity: Trump’s Blistering Pace

The speed with which the Trump administration has been carrying out its political program has been striking. Worried observers argue that the pace of Trump’s moves is unprecedented.79 The whirlwind of activity that has occurred within the U.S. government over recent months is certainly unusual for the country—Trump has rapidly upended many long-held norms and processes in his pursuit of executive dominance. But is the pace of Trump’s executive aggrandizement exceptional?

The conclusions that emerge from a comparative evaluation are concerning. Relative to other backsliding cases, the Trump team has acted with uncommon early momentum in its efforts to consolidate power. It has sustained its efforts simultaneously across multiple domains of American democracy, consolidating the process that many overreaching executives only achieve incrementally over a longer time. And the rapidity of Trump’s erosion of democratic norms has also been notable, even in comparison to other aggressive backsliding cases.

Early Momentum and Speed of Backsliding

The early and sustained speed of Trump’s executive aggrandizement sets the United States apart from other backsliding cases. Trump arrived at the presidency with immense power to enact his agenda. His party controls both houses of Congress. The Supreme Court is friendly to his administration. He fields a large, loyal base of politicians and citizens. Yet even with the typical levers of presidential power at his disposal, he chose not to move incrementally or play by the rules of the game before he began to upend democratic norms.

In comparison, backsliding leaders are often elected with a purported commitment to uphold or even strengthen their country’s democracy. They have been granted access to the levers of power through their electoral victory, and there is little pressing need to dismantle the system that—for the moment—serves their interests. While some leaders may take early steps to assert control over opposition-held institutions, the overreach process tends to be incremental.

Take Türkiye, for example, where Erdoğan’s consolidation of power came several years into his tenure as leader of the country. When the AKP and Erdoğan campaigned before first coming to power in 2002, they presented themselves as a democratic option for Turkish voters and promised to advance the rule of law, civil society freedoms, and Türkiye’s accession to the European Union. Indeed, in the initial years of Erdoğan’s tenure as prime minister, he was widely lauded internationally for his democratic leadership and liberal reforms—a marked contrast with the criticism the Trump administration attracted for its early disregard for democratic norms.80 Although this initial period did feature some encroachment on democratic institutions, Erdoğan’s erosion of Türkiye’s democratic institutions did not accelerate significantly until years later.81

India, too, exemplifies the gradualness that usually characterizes the common democratic backsliding model. Modi did not immediately dismantle democratic institutions at the outset of his tenure as prime minister in 2014. Rather, over the subsequent decade he has utilized his strong parliamentary backing and repressive techniques step by step to centralize power and create a culture of fear that prevents meaningful civil society mobilization or political opposition. His government only incrementally employed tools such as sedition laws, retribution against political opponents, and restrictions on media and civil society. These tactics are comparable to the United States, where Trump’s early assault on U.S. law firms through targeted executive orders quickly led other law firms to acquiesce to the administration’s demands. But while this unfolded over mere weeks in the United States, it was the accumulative use of such measures over years in India that has suppressed meaningful pushback by civil society and judicial bodies.82

Not all cases of backsliding unfold slowly. In some cases, leaders with backsliding intent enact an immediate, rapid agenda to overcome a position of political weakness. In Ecuador, for example, while Correa won the 2007 presidential election, he faced strong opposition in the legislature that posed a meaningful constraint on his political capacity. He quickly called for a constituent assembly, which he filled with political allies. With Correa’s backing, the constituent assembly suspended Congress and vested itself with the country’s policymaking powers, co-opting the legislature completely.83 But after Correa’s initial assault on the legislature, his subsequent overreach strategy did not sustain this initial momentum. His approach over the ensuing decade was certainly aggressive, but it proceeded more slowly and incrementally. By contrast, Trump faces no major legislative pushback to his agenda that would necessitate an early power grab of this type. He is operating from a position of power and seeking to amass even more power.

There are a few cases of executive-led democratic backsliding that more closely resemble the rapid approach of the Trump administration’s first few months. Poland’s democratic erosion, for example, was also characterized by a quick assault on democratic checks on the executive right out of the gate. PiS assumed power in October 2015 with a slim parliamentary majority. Almost immediately, the newly formed government moved to weaken the judiciary, media, and civil service. Within its first year, PiS undermined the Constitutional Tribunal by politicizing its appointments and limiting its oversight capacities, and—much like the Trump administration’s ongoing disobedience of judicial mandates—began rejecting tribunal rulings outright.84 It expanded government control over Poland’s public media services and used this power to purge critical journalists. And it politicized the country’s civil service through changes to the Civil Service Act—another move that parallels the Trump administration’s ongoing politicization of the federal bureaucracy.85

Hungary, too, saw a rapid expansion of executive power after Orbán and the Fidesz party regained power in May 2010. By the end of that year, the Fidesz government had packed key institutions and agencies with party loyalists, passed constitutional changes to weaken the oversight capacity of Hungary’s Constitutional Court, reduced the size of the legislature, eliminated funding for civil society groups, and passed new media restrictions.86 Much like the Trump administration, Orbán’s team asserted dominance over various levels of Hungary’s democratic system—from the co-opting of independent agencies to the weakening of civil society organizations. And, also like the Trump team’s approach, the Fidesz government enacted these changes with rapidity after assuming power.

Even in comparison to similar cases like Poland and Hungary, Trump’s actions over the past months reflect an unusually condensed timeline and rapid upending of democratic norms.

But even in comparison to similar cases like Poland and Hungary, Trump’s actions over the past months reflect an unusually condensed timeline and rapid upending of democratic norms. While the PiS and Fidesz governments each oversaw significant democratic erosion in their first year, the Trump administration compressed into its first weeks of overt defiance and institutional disruption of democratic systems what took months to unfold in these other cases. For example, steps comparable to the series of measures that Trump took in his early days to consolidate control over the executive workforce took form over a year-long period in Hungary.87 Trump’s team began to defy the judicial system in the first weeks of his presidency. In Poland, by contrast, while the PiS government moved swiftly to reshape the Polish judiciary, it was not until months into its tenure that the party began to explicitly deny the legitimacy of the courts.

Simultaneous, Multilevel Approach

In addition to the speed of the administration’s efforts, it is also notable that it has maintained this rapid approach simultaneously across the different domains of U.S. democracy. In other backsliding cases, leaders commonly targeted their country’s democratic checks in a piece-by-piece fashion. In Türkiye, it was through incremental changes over many years that Erdoğan weakened Turkish democratic institutions in changes like the 2010 constitutional referendum to increase the executive’s control over the courts and another referendum in 2017 to weaken the legislature and establish a system with an extremely powerful presidency.88 Correa’s approach was also less unified. Over a decade, he periodically targeted democratic institutions. He first created a new executive-aggrandizing constitution. Subsequently, his government pushed through constitutional changes that weakened the judiciary and the press. It was only later that Correa implemented stringent restrictions on civil society organizations and gatherings.89

The Trump team has not employed this sort of institution-by-institution approach. Rather, it has aggressively pursued all three levels of its aggrandizement agenda simultaneously. During his first week as president in January 2025, Trump issued a host of executive orders, statements, and restructurings that targeted the executive branch, horizontal institutions, and civil society. And in subsequent months, the three-level effort has not let up. His team has continued to exert dominance by stacking the different elements of his aggrandizement agenda into a compressed and simultaneous push that makes identifying and responding to its illiberal elements especially challenging for pro-democracy actors.

Severity: Some Limits—For Now

While the Trump administration’s pursuit of executive dominance has been particularly fast, the degree of democratic erosion in the United States is not yet as severe as that of most of its backsliding peers. Most of America’s democratic institutions and processes remain intact, protected by the Constitution and other U.S. laws. The administration’s policies and procedures have undermined democratic norms, but its aggrandizement agenda is not, at least yet, as deeply institutionalized as in the majority of the comparative cases studied. And U.S. democracy has not devolved to the levels of political violence and repression that characterize some of the backsliding countries in this study and beyond. Yet while the United States might not have slid as far toward autocracy as many democracies before it, the weakening of what were previously viewed as unusually strong democratic guardrails is nevertheless unprecedented in modern U.S. history and deeply troubling.

Non-institutionalized Backsliding

Democratic erosion has thus far been less institutionalized in the United States than in most of the comparative backsliding cases. For example, to weaken horizontal checks on the executive, Trump’s primary tactic has been the erosion of democratic norms—that is, the informal, unwritten rules of democracy—rather than structural, legal change. As discussed above, the administration has prioritized efforts to delegitimize the judiciary. This approach could ultimately pave the path for the structural weakening of the judiciary, as the Turkish case exemplifies. And the Supreme Court’s ruling in June limiting the ability of federal courts to issue universal injunctions is for some observers a worrying development in this direction.90 But the U.S. case still does not entail the types of structural judicial changes that eliminated Polish judicial independence or weakened the authority of Ecuador’s courts.

To weaken horizontal checks on the executive, Trump’s primary tactic has been the erosion of democratic norms—that is, the informal, unwritten rules of democracy—rather than structural, legal change.

Brazilian judicial delegitimization under Bolsonaro is a more similar case of normative rather than institutional democratic decline with regard to the judiciary. As outlined above, Bolsonaro leaned heavily into verbal assaults on Brazilian courts and never translated this into structural changes to Brazil’s judiciary. Throughout his tenure, the judicial system remained an independent and important democratic check on his illiberal agenda. Trump’s attacks on U.S. courts have already gone further than Bolsonaro’s—including the outright defiance of court mandates. But like Bolsonaro, Trump and his administration have not sought constitutional change or legislative avenues to override the authority or independence of America’s judiciary.

Similarly, though Trump has bypassed Congress through various evasive maneuvers, he has not rewritten the rules of legislative procedure or implemented structural changes to constrain the legislature. This sets the United States apart from the other presidential cases in this study, like Ecuador, in which illiberal leadership fundamentally altered legislative institutions, functionally eliminating their capacities to constrain the executive. While a Republican-led Congress might not present meaningful checks on Trump’s executive actions out of party loyalty, the lack of institutional weakening may provide avenues for democratic pushback or recovery down the road.

While a Republican-led Congress might not present meaningful checks on Trump’s executive actions out of party loyalty, the lack of institutional weakening may provide avenues for democratic pushback or recovery down the road.

The Trump administration’s efforts to weaken societal constraints on the executive have also been characterized by a lower degree of institutionalization compared to other executive aggrandizement cases. For example, a common tactic among backsliding leaders is their use of legal restrictions on civil society organizations or individuals to dampen societal pushback or constraints. In Ecuador, Correa’s allies passed laws in 2013 that mandated that organizations report on their activities to the government, banned “partisan activities,” and shut down groups that participated in advocacy against government policies.91 In India, Modi’s government has cracked down on societal dissent, relying on sedition laws and restrictions on free speech to police its public.92 This has not yet been the case in the United States. The Trump administration’s targeting of individuals, law firms, and universities has undeniably had a chilling effect on public institutions and civil society groups—and there are worries that legal restrictions might still emerge. But as of now, U.S. civil society remains free of broad restrictions and vertical accountability remains a viable check on executive power.

The Trump administration’s tactics to repress critical media reflect a similar overall pattern as found in other backsliding regimes but are not yet as institutionalized as in other cases. Trump and his team have targeted certain news sites with investigations and lawsuits, restricted press groups from accessing government events, and repeatedly attacked or criticized journalists and news organizations. Several of these tactics do echo cases like El Salvador, Hungary, Poland, and Türkiye, where backsliding leadership frequently delegitimized the press and used strategic lawsuits to weaken independent outlets. But in comparison to such cases, the Trump administration has not gone as far in its efforts to legally constrain or co-opt independent media. Under the Fidesz administration in Hungary, for example, the government acquired media companies and compiled them under the Central European Press and Media Foundation in 2018, ensuring that pro-government coverage dominated the country’s media ecosystem. In Poland, too, gaining control over the country’s largest public media companies gave PiS the ability to skew coverage of the administration and was a difficult institutional change for the subsequent administration to untangle.93 In Türkiye, the Erdoğan government used legal punishment to silence critical press and pushed for the sale of media outlets to pro-government companies.94 Whether the Trump administration will succeed in codifying such restrictions remains to be seen, but U.S. media is less structurally constrained or imperiled than in other important cases.

The emphasis that the Trump administration has placed on restructuring the executive branch is an exception to this overall low level of institutionalization. However, even in this domain, the Trump administration has not formalized its changes through legislative or constitutional changes. Instead, his team has primarily employed a combination of personnel changes and procedural shifts. To target federal agencies focused on oversight and accountability, for example, Trump fired leadership at the Office of Special Counsel, the Office of Government Ethics, the National Labor Relations Board, the Federal Trade Commission, and others. And he has used executive orders to mandate greater White House oversight of independent executive agencies, to change procedures to make it easier to fire civil servants, and to politicize the federal hiring process.

In the common backsliding model, this subjugation of executive agencies and workers is often enshrined in more formal ways. Türkiye is an extreme example, where Erdoğan’s AKP party successfully amended the Constitution in 2017 to formalize presidential dominance over the executive branch. These changes eliminated the prime minister role, establishing the Turkish president as head of both the state and executive, expanding his power to unilaterally select his officials without parliamentary oversight, and granting him the authority to shape the executive branch and create new ministries.95 In countries like Hungary and Poland, too, efforts to cement the new leadership’s control over civil servants and the state administration were enacted through legislation.96

Across the three levels of the Trump administration’s aggrandizement project, democratic erosion has not become as deeply rooted as it has in many other backsliding cases. In the years to come, it remains to be seen whether the administration will seek to and succeed in more firmly institutionalizing its executive aggrandizement, or if U.S. checks and balances will prevent it from doing so.

Limited Repressive Measures

The degree of repression inflicted on political and civic opponents by the Trump administration is lower than what occurred in most of the comparison cases. On one hand, through their retributive actions and rhetoric, and their constant use of extreme political language, Trump and his team have contributed significantly to an increasingly retributive U.S. political culture. Trump has, for example, persistently attacked judges and other elected officials, and research has found that such comments have coincided with “escalating violent posts on social media,” where threats of violence and calls for impeachment against judges have risen “327 percent between May 2024 and March 2025.”97 But the administration has not widely used coercive force or criminalization to sideline political opposition, silence critical media, or dampen societal pushback.

In contrast, Erdoğan’s government collaborated with allied prosecutors, judges, and police to arrest more than 700 people between 2007 and 2012—from military officers to academics and journalists—on fabricated charges of plotting a coup.98 In subsequent years, the AKP has also imprisoned major opposition figures, including opposition presidential candidate Selahattin Demirtaş in 2016 and Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu in 2025, thus pushing Türkiye toward full authoritarianism.99 In El Salvador, Bukele leveraged his emergency powers to deploy the military and curtail civil liberties in 2022. His forces cracked down on civilians, resulting in widespread imprisonment and violence.100 In Brazil, Bolsonaro greatly eroded civil-military boundaries, giving the military deep influence over government institutions, cultivating a militarized civic culture, and empowering the military to engage in aggressive policing tactics throughout the country.101 Other backsliding cases beyond the focal set of this study, such as Myanmar, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, have involved overt and pervasive political violence.102

Thus far, the U.S. case more closely resembles countries where elite-led polarization has contributed to increasingly violent political cultures more than it has produced overt government repression—like India, where Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda has fomented deepening sectarian polarization and vigilantism within Indian society.103 Of course, it is still early into the administration, and other backsliding leaders often only initiated more violent tactics later into their backsliding drives. Most worrisome in this regard have been the administration’s extremely harsh tactics in its deportation policies, and the almost reflexive militarization of its response to protests on that issue.

Conclusions

President Donald Trump’s effort to consolidate executive dominance over all parts of the U.S. political system parallels the campaigns of executive aggrandizement carried out by autocratically inclined elected leaders in numerous other countries in recent years. At the same time, some of Trump’s key tactics—such as dominating and weakening the executive branch, delegitimizing and circumventing horizontal institutions, and leveraging funding and procedural restrictions against sites of societal pushback—are less common in other cases, where executives assume automatic acquiescence from executive agencies and bureaucracy, handily disempower the legislature and judiciary through constitutional changes, or push through laws that criminalize dissent and restrict civil society’s freedoms. Facing the strong institutional constraints and norms that underpin U.S. democracy, Trump’s team cannot simply follow the exact same backsliding playbook that has served executives in weaker or less consolidated democracies around the world. Instead, it must target checks and balances that are unique to the American system, using the narrower set of tools that are available to a U.S. president.

Nevertheless, the aggressiveness of Trump’s executive aggrandizement is worrisome. Despite the relative strength of U.S. democratic constraints, Trump has pursued his agenda with a speed that outpaces even some of the most rapid cases of democratic erosion, like Hungary and Poland. And compared to the backsliding approaches taken in countries ranging from Ecuador to India, the Trump team’s approach has been more immediate and expansive than is common. It may seem comforting that despite this rapidity, U.S. democratic backsliding is still less institutionalized or overtly repressive than many other backsliding cases. But in light of the high barriers to democratic erosion in the United States, what makes the current context especially troubling is not the relative extremity of Trump’s executive aggrandizement, but how fast and systematically he has achieved these aims within a democratic system once thought to be impervious.

It remains to be seen how far Trump intends to go in his aggrandizement agenda. But assessing the U.S. case in comparative analysis helps make sense of the constraints facing the administration and the pathways available to it moving forward. These conclusions start to provide lines of analysis for those who are focused on how to respond. Pushback against the administration’s strenuous, multipronged effort at executive aggrandizement, for example, will only be systematically effective if it is at least somewhat coordinated across multiple sectors and meets the Trump administration’s simultaneous assault across different political levels with a parallel set of multilevel efforts at constraint.

Additionally, while Trump has sought to project immense power by shattering so many democratic norms so quickly, the focal areas of his drive reveal that his administration still faces numerous constraints within U.S. democracy that pro-democracy actors can and should leverage, including 1) an executive branch that still has internal accountability mechanisms and constraints on unfettered presidential power, 2) a legal system that makes constitutional change very difficult, 3) a legislature with many veto points, and 4) a well-resourced private sector, a historically independent media sector, and a comparatively well-resourced nonprofit sector.

Finally, the comparative perspective highlights that U.S. democratic backsliding is not yet deeply rooted or severe, leaving significant space for pro-democracy actors to engage. But these responses must come soon, be sustained, and be ready to weather worse times ahead. As the Trump administration continues to amass power around a president driven by a reflexive intolerance toward criticism and opposition and a willingness to try to overturn any norm, process, or institution in his path, the deep roots of American democracy will be put to a full test in the months and years ahead.

Acknowledgments