Summary

Technology firms are among the major backers of efforts to spur a nuclear energy renaissance in the United States to fuel data centers that run AI and cryptocurrency operations. While this creates hopes for a nuclear energy expansion, there are social costs that need to be addressed to ensure that these plans do not encounter challenges over the next few years caused by public opposition. These costs have to do with limited direct economic benefits to host communities but increased environmental and health concerns at a time of precipitous decline in the federal government’s willingness and capacity for regulating nuclear energy systems. What should policymakers do to address the social costs of the AI-led nuclear energy renaissance currently unfolding? Fully understanding these potential costs and their implications is the first step.

Introduction

Over the past several years, there have been renewed hopes for a nuclear energy expansion in the United States. Big technology companies such as Microsoft, Meta, OpenAI, and Amazon are among the major backers as they seek to meet the high energy needs of data centers. Since the launch of generative AI, which is more energy-intensive than older AI models, nuclear energy has emerged as a top choice for Silicon Valley firms looking for a reliable solution to their electricity needs. Generative AI needs more electricity because it creates new images and texts, and not merely patterns from big data as older AI models have been doing. In the past decade (2014–2024), data centers used only 4.4 percent of total U.S. electricity production, but that number is expected to increase at least threefold to 12 percent by 2028 because of the exponential growth in use of generative AI.

Coincident with private sector support, there is also growing political momentum for a nuclear energy renaissance, as evidenced by recent governmental actions. In May 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump signed four executive orders to expand nuclear energy production in the United States; he called for quadrupling domestic production of electricity from nuclear power within the next twenty-five years. The current administration’s policy to increase nuclear energy production builds on that of its predecessor. During former president Joe Biden’s administration, the U.S. Congress passed the ADVANCE Act in July 2024 to hasten the deployment of advanced nuclear reactors, while the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act also provided tax credits to qualifying nuclear power facilities.

Against this backdrop of heightened corporate enthusiasm for nuclear energy and support from the federal government, potential social costs of an AI-fueled nuclear renaissance have not found much discussion in the public policy space. Yet if not understood and accounted for in plans for a nuclear energy expansion, these costs could derail implementation. What are some of the social factors that could disrupt such an expansion? What can be done to address these factors?

Big Tech Goes Nuclear

A key argument often made in favor of using nuclear power for data centers is that it provides “firm power,” that is, a consistent source of electricity, making it more reliable than intermittent sources like wind or solar energy. Because generative AI requires massive and reliable electricity sources, firm power is highly appealing to the Silicon Valley firms that have emerged as the newest advocates for a nuclear energy renaissance in the United States.

One example is the Stargate Project, announced by Trump, which is seeking $500 billion in investments to build data centers for AI infrastructures. Stargate plans to draw nuclear power from a fleet of small modular reactors (SMRs), whose prototypes have not yet been built in the United States. It also plans to use solar power and battery storage. The first Stargate site is currently being built in Abilene, Texas. OpenAI, SoftBank, Oracle, and MGX are Stargate’s lead investors, along with Microsoft and Nvidia as Stargate’s partners.

Because generative AI requires massive and reliable electricity sources, firm power is highly appealing to the Silicon Valley firms that have emerged as the newest advocates for a nuclear energy renaissance in the United States.

Similarly, the advanced nuclear reactor startup Oklo signed a nonbinding agreement with AI data center provider Switch to develop nuclear facilities to provide 12 gigawatts of electricity to data centers through 2044. OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman—who until recently chaired Oklo’s board—is a major advocate for SMRs powering data centers across the United States. These are but two of the several notable partnerships involving technology companies and nuclear vendors.

Private Interests, Social Risks

The potential heavy inflow of private capital for nuclear energy feeds great optimism for a major expansion in deployment of nuclear power stations. Yet serious consideration is needed of the implications of major private sector involvement in nuclear power, including the use of new designs by new vendors, for new applications, in non-traditional locations. It is also useful to consider where there is need for a “new nuclear responsibility” commitment by relevant stakeholders to ensure that a nuclear energy renaissance led by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs is safe, secure, and reliable.

The role of private enterprise in nuclear energy innovation and promotion in the United States is not new, but historically the federal government has provided strong guidance and oversight. For example, companies like Dupont, Union Carbide, Westinghouse, and Bechtel participated in the Manhattan Project, and the government later sought to encourage public utilities, reactor suppliers, and the U.S. public to accept this new form of electricity by subsidizing costs, underwriting risks, and assuring redressal against health risks. These U.S. government roles were legislated in provisions such as the 1954 Atomic Energy Act and the 1957 Price-Anderson Act.

In addition, the U.S. government has played a significant role in regulation and remediation in nuclear energy throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, through programs operated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Environmental Protection Agency. Today, both bodies are facing funding and personnel cuts as part of the Trump administration’s efforts to shrink the federal government in the name of greater efficiency. Thus, at a moment of precipitous decline in the regulatory capacity and economic resources of the federal government, corporations with deep pockets—a large number from Silicon Valley—have become the predominant actors, along with heavy industry, utility companies, and state governments such as New York, in pushing a nuclear energy renaissance. On one hand, this has led to the potential for massive flows of private capital spurring innovation in advanced nuclear reactors, such as SMRs and microreactors. On the other hand, it means corporations are poised to be among the largest consumers and beneficiaries of the electricity that would be produced from both new and re-licensed reactors, instead of host communities and nearby major urban centers.

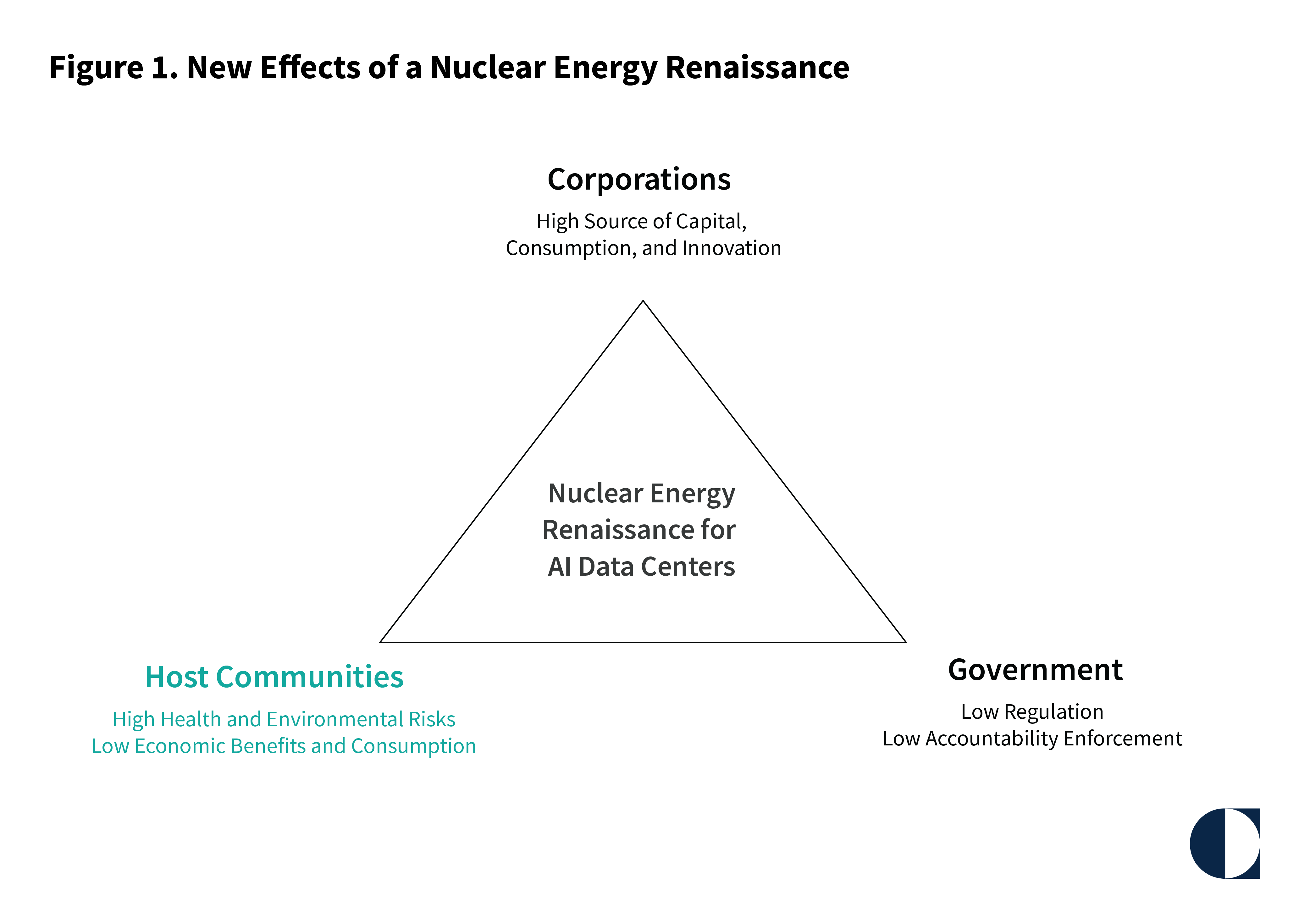

This situation, in which corporations wield more power than the government, is not an unfamiliar story in the United States, but it is new in the nuclear energy space. It also carries with it great risks, given the serious environmental and health risks from radioactive waste and accidents. The triangular relationship, represented in figure 1, between corporations, the federal government, and host communities needs to be managed in a way that facilitates nuclear energy expansion without engendering public opposition. At present, corporate proponents of nuclear energy expansion are the sources of both capital and innovation, as they are the ones pushing for new reactor technologies. Since data centers to run generative AI operations are at the center of this new push toward nuclear energy expansion, corporate actors will be the main consumers of the electricity to be generated. Currently, the federal government and host communities have weaker positions within the triangular relationship because of reduced regulatory capacity, low direct economic benefits, and increased health and environmental risks.

Historically, the state’s regulatory role has been pivotal in protecting communities from risk, such as by managing toxic waste from the chemical industry or enforcing safety features in the aviation and automotive industries. Traditionally, the NRC has played a significant role in keeping nuclear energy safe, secure, and reliable in the United States. The Trump administration’s efforts to curtail the NRC’s regulatory capacity pose challenges to societal interests, especially at a time of imminent expansion of nuclear energy production in the country to feed data centers.

The Trump administration’s efforts to curtail the NRC’s regulatory capacity pose challenges to societal interests, especially at a time of imminent expansion of nuclear energy production.

The next sections present six new challenges posed by the current moment of promise, coupled with three policy recommendations.

New Challenges

There are six social risks that pertain to a private sector–led nuclear energy renewal in the United States. These relate to corporate consumption, health and environmental damage and water scarcity, limited employment, reduced regulation, and timing.

First, nuclear energy is poised to become increasingly a private good such that electricity from new and newly reopened reactors could power data centers rather than homes. This could make companies that own or operate data centers the direct consumers of the electricity generated. Alternatively, it could come about through offtake agreements between tech companies and utility providers to reroute a certain amount of electricity from preexisting nuclear power plants, such as the one between Talen Energy and Amazon Web Services to supply 1,920 megawatts of electricity through 2042 from Talen’s Susquehanna nuclear plant in Pennsylvania to power Amazon’s nearby data center. In that case, community opposition forced revisions to the original agreement such that Amazon was required to draw from the overall electricity grid instead of directly from the nuclear power plant. The risk of offtake agreements is that utility ratepayers pay higher electricity prices as a result of data center energy consumption, that either removes nuclear power from the grid or adds nuclear power at significantly greater cost to consumers.

Second, a major increase in nuclear power will exacerbate an existing spent nuclear fuel and waste disposal problem, for which there is no agreed political or technical solution in the United States. It is the policy of the NRC to store spent nuclear fuel in specially designed pools at reactor sites for a certain period before placing it into dry casks. The United States does not have a program for consolidated interim storage, let alone a permanent repository, for used power reactor fuel, meaning that nuclear power states will be de facto nuclear storage sites. Over time, this could pose increased risks to surrounding communities through groundwater contamination from radioactive materials such as tritium resulting from system leaks, condensation, and evaporation.

Third, water scarcity is another major issue for nuclear power plant host communities to contend with. Not only do data centers need large supplies of water for cooling—so do nuclear reactors. Boiling water reactors, pressurized water reactors, and even many of the widely anticipated SMRs use ordinary water as coolant. In the United States, two-thirds of data centers constructed since 2022 have been built in places that already experience water stress, such as California, Texas, and Arizona. Data centers that do not run on nuclear power are already creating water shortages in places such as Georgia. Co-location of data centers with nuclear power plants would cause further strain on local water sources, potentially causing severe water shortages. In other words, not only could host communities have to absorb higher electricity costs from reactors built in their vicinity with data centers running AI operations, but those communities could also experience increased risks of water scarcity and environmental and health damages.

Co-location of data centers with nuclear power plants would cause further strain on local water sources, potentially causing severe water shortages.

A fourth social risk stems from a different benefit calculus for host communities. SMRs, which are at the forefront of this renaissance, would create fewer jobs than the traditional large power reactor projects of the past century, thereby limiting direct economic benefits to host communities. The argument in favor of SMRs from the nuclear power industry is that they would be faster and cheaper to build, avoiding the delays and cost overruns that have plagued large reactor projects. In particular, SMR developers tout that they could mass-produce reactor components in factories and install them on site. But this also means that there would be less labor needed to build and operate these reactors, leading to lower economic payoff for neighboring communities.

Fifth, the public will have less independent regulatory assurance than it once did in the safety and security of new reactors as well as in the maintenance of preexisting ones. Trump’s executive orders from May 2025 aim to drastically reduce the power of the NRC, the federal government’s independent regulatory body, in the name of “national- and economic-security interest.” The administration blames the NRC for what it called “50 years of overregulation” hampering nuclear industry growth since 1978. This implies that state stewardship of nuclear power plants is unlikely to continue at previous levels.

Reforming the NRC at a moment of nuclear energy renewal raises a host of risks. The reduced authority of the NRC could prevent host communities from getting information about and remediation for environmental and health risks of nuclear reactor sites close to their homes. It could also reduce public confidence in nuclear power, especially since SMRs are still a relatively new technology that will need oversight in these early years of construction and operationalization. This low capacity for regulation and accountability enforcement by the federal government would harm those who are the least powerful: host communities and nearby urban centers.

The reduced authority of the NRC could prevent host communities from getting information about and remediation for environmental and health risks of nuclear reactor sites close to their homes.

Sixth and finally, for tech entrepreneurs who are pouring billions of dollars into nuclear energy to run energy-intensive AI operations in their data centers, timing is key. They might lose interest if the nuclear energy fleet does not join the grid when they need it the most—in the next two to five years. Not only could this lead to a plethora of unfinished nuclear reactor projects across the country that serve no economic purpose, but the push for faster results itself might lead to cutting corners on safety, exacerbating risks for host communities.

Policy Recommendations

The power disparity between corporations and the federal government on one hand, and host communities on the other, could be mitigated through three specific steps.

First, proactive state-level and local governments and individual responsible lawmakers are essential to protect host communities against the social risks of an AI-led nuclear energy renaissance. At a time when the federal government is fast retreating from the regulatory space, the role of local governments is key to keeping nuclear energy safe, secure, and reliable. States such as Pennsylvania, Texas, Georgia, Arizona, and others where large data centers are being built, or where preexisting nuclear reactor sites are being connected to data centers, can play a pivotal role in addressing the needs of host communities. Social risks are local and localized, and lawmakers have to heed the needs of their constituents to mitigate the potential for mass public opposition to nuclear energy growth in the United States in the coming years. While public opinion remains generally positive, building consensus among constituents for nuclear energy will be essential, which underlines the significant role to be played by state and local governments.

Proactive state-level and local governments and individual responsible lawmakers are essential to protect host communities against the social risks of an AI-led nuclear energy renaissance.

Second, since nuclear energy growth has not materialized for decades, there is a dearth of expertise and marked lack of awareness in the federal legislative branch of risks posed by nuclear infrastructures in terms of terrorism, safety, and health. Nuclear knowledge management through technical and policy expertise is important for nuclear safety. A congressional caucus to discuss pertinent issues related to the anticipated nuclear renewal—such as the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy that was created to develop U.S. policy on nuclear energy matters from 1946 to 1977—could help address this knowledge gap. This would bolster policy expertise in the U.S. Congress, encouraging informed decisions regarding advanced nuclear reactors and technology entrepreneurs’ stewardship of nuclear energy. The Advanced Nuclear Caucus in the Senate and the House American Energy Dominance Caucus could become potential platforms for nuclear energy–related knowledge management and eventually policymaking.

Third and finally, with the NRC’s federal oversight role under fire, the NRC should feed its institutional repertoire of technical expertise in nuclear energy matters across the fuel cycle more directly into state and local regulatory bodies. While the NRC is an independent government regulator to ensure safety of nuclear infrastructures, recent developments indicate that its independence is being drastically reduced. One way to address the imminent decline in expertise could be to create proactive state-level independent nuclear regulatory bodies from the preexisting NRC regional offices that would undertake the tasks of the NRC at the state and local levels to ensure nuclear safety. However, this would require state-level stewardship to ramp up at a time when federal regulatory capacity and authority are in decline.

Conclusion

Policymakers need to address the social risks inherent in the nascent nuclear energy renaissance soon in order to ensure that public opposition does not derail future nuclear energy expansion in the United States. The current push toward nuclear power to run data centers poses numerous issues: shifting corporate costs and risks to ratepayers and host communities; water scarcity; limited employment; loss of public trust through compromised regulatory autonomy; and questionable timing. The solutions to these issues concentrate on policy innovations at the state level to address the local needs of host communities, effective nuclear knowledge management, and tapping expertise from the NRC’s regional offices to build new state-level independent regulatory bodies in the nuclear energy arena.

.jpg)

.jpg)