A prophetic Romanian novel about a town at the mouth of the Danube carries a warning: Europe decays when it stops looking outward. In a world of increasing insularity, the EU should heed its warning.

Thomas de Waal

Source: Getty

Turkey seeks to position itself as a key peacemaker and regional hub in the South Caucasus. To achieve this, Ankara should move beyond nationalist rhetoric toward a more pragmatic, strategic approach rooted in the international legal order.

Armenia-Azerbaijan-Turkey relations resemble the proverbial Gordian knot—the famous tangled rope in an ancient town in what is now Turkey that no one could untie. Alexander the Great famously solved the problem by cutting the knot with a sword. If any of the three countries can copy Alexander and cut the knot, it is the most powerful of them: Turkey. But can and will Turkey take that step?

The fraught diplomacy between Ankara, Baku, and Yerevan lacks the necessary decisive action to achieve a breakthrough. Turkey’s relationship with Armenia is tied to Armenia-Azerbaijan relations and an ever-elusive peace agreement between the two. The absence of a deal fuels geopolitical rivalry in the South Caucasus, which poses a systemic threat to all three states in the region and leaves them vulnerable to spillovers from conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine. That denies Turkey its strategic potential as a middle power and a stakeholder in Eurasian connectivity.

By providing military, political, and diplomatic support to Azerbaijan during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Ankara positioned itself on one side of the conflict while also advocating its role in conflict management. In contrast to Moscow’s phantom and performative peacemaking, Turkey’s involvement was unambiguous, coercive, and militarized.

Despite Ankara’s role in the war and its political costs for the government of Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, Yerevan has been steadfast in calling for a full normalization of relations with Turkey. Meanwhile, Russia’s unprecedented diplomatic and political decline in the South Caucasus has created an opportunity for Turkey to exercise regional leadership as a responsible middle power. Such players use soft power effectively, build principled coalitions with major and emerging states, and balance domestic capacity with regional limitations.

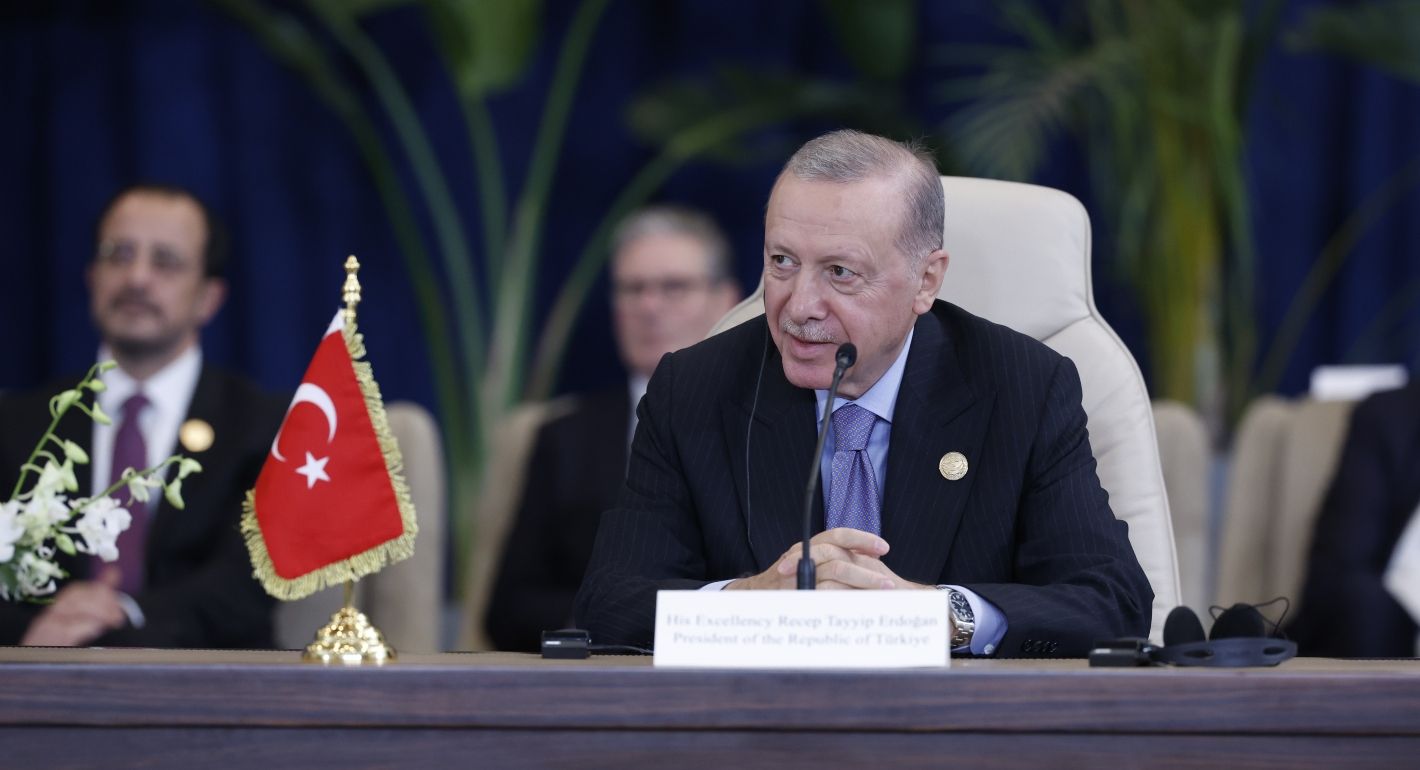

Realizing its potential as a middle power in the South Caucasus would enhance Turkey’s leverage in Eurasia and contribute to durable peace in the region. Instead, Turkey’s foreign policy under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has become bilateral, transactional, and personalized, limiting its economic and political reach. As a result, Ankara lacks the institutional drivers to exercise its role as a middle power in its neighborhoods.

By tying its potential rapprochement with Armenia to the peace process with Azerbaijan, Ankara has increased Baku’s hold over the South Caucasus at its own expense. Turkey has turned Azerbaijan into a veto player over Turkey’s policies in the region, significantly offsetting Russia’s decline. To realize its potential as a regional middle power, Ankara needs to delink the Armenia-Azerbaijan normalization process from its bilateral relations with Yerevan. This will increase Turkey’s leverage in the South Caucasus relative to that of its traditional competitors in the region.

Since the end of the Cold War, Turkey’s foreign policy has undergone a significant transformation. It has shifted from a strategy of regional integration and mediation—marked by free-trade agreements and diplomatic efforts between Israel and Syria as well as in the Western Balkans—toward a more assertive and militarized posture, characterized by strategic autonomy, coercive diplomacy, and interventionism.

As researchers Mustafa Kutlay and Ziya Öniş argued in a landmark study on Turkey in the post-Western order, several key drivers explain this shift. Great-power transitions have led to the relative retreat of the West and the rise of new power centers, creating opportunities for middle powers like Turkey. There are new spaces for middle powers to assert themselves, but these powers’ capacity to adapt global rules to regional contexts and make the global order work through regional systems is uneven and fluid.

Indeed, Ankara has been criticized for moving toward a risk-prone foreign policy under Erdoğan. In an interview for this article, Selim Yenel of the Global Relations Forum in Istanbul argued that this move has isolated Turkey in the Middle East and the broader Mediterranean.1 Instead of the strategic autonomy that Ankara sought, Turkey has found itself in new dependencies on larger powers like Russia as well as smaller ones such as Azerbaijan, particularly in the area of energy security.

Other analysts have highlighted Turkey’s authoritarian populism as a factor in its evolving foreign policy. This development—also visible in Brazil, Hungary, and India—has led to the hyperpersonalization and politicization of foreign policy. In Turkey, the line between domestic and foreign policy has largely dissolved. One correspondent noted that Erdoğan’s foreign policy is now inseparable from his personal political agenda. As former diplomat Osman Sert of the Ankara Institute noted in an interview,2 geopolitics today is increasingly shaped by leader-to-leader dynamics rather than by institutional frameworks. Erdoğan has used foreign policy as a tool for his domestic political survival by deploying nationalist rhetoric and military operations in places such as Azerbaijan, Libya, and Syria, but with little strategic leverage when it comes to Turkey’s global position.

The implications of Ankara’s shifting foreign policy have played out in its changing approaches to conflict management. Turkey’s conflict management in the early 1990s was traditional and accommodationist, aligned with the liberal international order. Specifically, Turkey’s early post–Cold War foreign policy featured structural conflict prevention, which emphasized legal and political institution building, negotiated settlements, and conflict-sensitive development assistance.

From 2011 onward, the Arab Spring and the Syrian Civil War marked a turning point, leading Ankara to adopt a mixed approach that combined traditional third-party roles with deterrence-based and peace-enforcement strategies. As Turkey experienced democratic backsliding and embraced strategic autonomy, these third-party roles shifted toward hard power and coercive diplomacy, including military interventions.

Ankara also faces a mismatch between its domestic policy priorities and its geopolitical imperatives, even in its exercise of strategic autonomy. In fact, Turkey’s practice of strategic autonomy has been reduced to hedging, which has delivered little in the way of room for maneuver either regionally or globally. Mustafa Aydın of Kadir Has University put it succinctly in an interview that Turkey has been more effective in denying the West foreign policy maneuverability than in establishing an alternative regional order.3

These shifts in Turkish foreign policy marked a clear departure from its traditional parameters. Ankara became more deeply involved in the domestic affairs of neighboring states, adopted a narrowly sectarian lens in its foreign relations, and began to invoke universal human rights while selectively extending protection to particular groups. Carnegie’s Alper Coşkun and Sinan Ülgen have linked these changes to transformations in Turkey’s political institutions. After losing its parliamentary majority in 2015 for the first time in thirteen years, the previously dominant Justice and Development Party (AKP) turned to coalition politics, aligning with the hypernationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to maintain control of the legislature.

These evolving political dynamics, combined with broader deinstitutionalization, personalization of power, and democratic backsliding, have fueled the rise of nationalist ideologies that shape Ankara’s regional engagement. As one correspondent in Turkey observed, this turn toward nationalism and sectarianism created an opening for Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev by enabling Baku to position itself strategically within Turkey’s political system.

More relevant in the context of the Gordian knot in the South Caucasus is Turkey’s anti-Western turn and its fusion of Islamist and nationalist discourses. This development has generated political dividends for Erdoğan but has done little to advance Turkey’s regional and global strategic interests.

Turkey’s role in the fraught relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan has vacillated between a bystander and a partisan supporter of Azerbaijan during the 2020 war. Most significantly, Ankara played no part in the shaping of the parameters of the August 8, 2025, summit between the Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders in Washington. The meeting was the culmination of intensive diplomacy under the administration of former U.S. president Joe Biden and received a final push under President Donald Trump—a rare case of policy continuity between the two.

The summit produced an agreement to reopen regional transportation routes, grounded in respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity. The accord emphasizes reciprocity: On the one hand, it enables connectivity between Azerbaijan’s mainland and Nakhchivan exclave via Armenia’s southern border route, dubbed the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP). On the other hand, the agreement enhances Armenia’s international and domestic connectivity through Azerbaijan.

Yet, the summit transpired without Turkey’s input, despite Ankara’s capacities to advance open regionalism in the South Caucasus, defined as trade liberalization, regional connectivity, and regional governance. The TRIPP undermined the previous approach of a coercive, extraterritorial corridor through Armenia, which was pushed by Baku and Moscow with Ankara’s backing. The Washington accord challenges this preference by reaffirming the global norms of territorial integrity, sovereignty, and the inviolability of international borders. Indeed, mutual acceptance of territorial borders has been the most common mechanism for the prevention of armed conflict globally since the early twentieth century.

The Washington agreement also creates an opportunity for the South Caucasus to build a new connection between Europe and Asia. This would integrate the region into global networks and remove distortions in trade and transit—obstacles that have plagued the region in the context of Eurasia’s strategic geography. The deal therefore brings the South Caucasus a step closer to untying the Gordian knot, with Turkey well placed to help shape the regional order in line with Washington’s principles.

After the Washington summit, Turkey’s special envoy for normalization with Armenia, Serdar Kılıç, crossed the two countries’ land border, which has been closed for more than three decades, for a meeting in Yerevan with his Armenian counterpart, Ruben Rubinyan. Turkish Airlines, Turkey’s flag carrier, announced its intention to launch a route to Armenia, pending demand for the service. In October 2025, Rubinyan unveiled plans to restore the Gyumri–Kars railroad, which connects the two countries.

Despite the slow thaw in relations between Ankara and Yerevan, the Washington summit did not elicit any bold diplomatic approach from Turkey to capitalize on the opening created by the meeting. Indeed, while Turkey welcomed the agreement, Ankara’s statements and diplomatic language quickly reverted to the familiar, narrowly framed, nationalist rhetoric of supporting “the dedicated endeavors of our brotherly Azerbaijan.” On August 21, Turkish Transportation and Infrastructure Minister Abdulkadir Uraloğlu continued to use the language of “corridors,” even though the new deal’s key principles contradict this approach. He announced the intended completion of the so-called Zangezur Corridor between mainland Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan, with an extension to Turkey, emphasizing that the route would enhance connectivity across the “Turkic world.” Many newspapers continue to refer to the TRIPP as a corridor, with some falsely claiming that even Trump uses this characterization.

Perhaps the most significant test for Ankara after the Washington summit is whether Turkey will move forward with normalizing relations with Armenia and opening the border—or defer once again to Aliyev’s snowballing demands, which include an insistence on constitutional amendments in Armenia as a precondition for signing the already finalized peace treaty.

The most critical strategic loss for Ankara in today’s South Caucasus is its inability to translate its middle-power capabilities into an improved position in the hierarchy of global politics. The Washington summit has only heightened this reality.

Middle powers like Turkey exercise conflict diplomacy and mediation in their neighborhoods to enhance their power-projection capabilities. Indeed, conflict diplomacy is a valuable marker of these capabilities globally and regionally. Rising powers, which seek to manage great-power politics to their advantage, are increasingly active in conflict management in their own regions and farther afield. For example, Brazil’s peace-building activism since the 2000s has included involvement in Angola, East Timor, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, and Mozambique.

Ankara’s diplomatic self-restraint is partly explained by the “one nation, two states” narrative, which refers to Turkey and Azerbaijan’s shared Turkic identity and has shaped Ankara-Baku relations since the early 1990s. This framework justified Ankara’s full support for Baku during the 2020 war and its deference to Azerbaijan since. Scholars and correspondents linked this alliance to Turkey’s broader nationalist foreign policy, which includes outreach to Turkic states in Central Asia. As a result, Ankara’s rapprochement with Yerevan has been tied to Baku’s preferences, effectively granting Azerbaijan veto power over Armenia-Turkey relations.

It is also possible that Ankara has more strategic goals in mind when playing the role of bystander to the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process. Turkey’s reluctance to get involved may be a sign of a free-rider strategy, which helps middle powers support the liberal world order. This free riding makes sense for a middle power like Turkey, as it allows the country to avoid the complex entanglements that a more proactive conflict-management role would entail. Even great powers pursue free riding: India’s reluctance to engage in conflicts in South Asia and China’s avoidance of entanglement in the Middle East are notable examples.

Yet, the TRIPP initiative creates an opening for comprehensive connectivity in the South Caucasus, with the potential to elevate Turkey’s strategic position in the global economy. By diversifying its trade and transit routes, Ankara can strengthen its role as a central hub in Eurasia’s political geography. As Turkish economist Güven Sak noted in an interview,4 enhanced connectivity through the South Caucasus—including an open border with Armenia—would increase Turkey’s value for the EU. Diversified links could boost Turkey’s export competitiveness, deepen its value chains with Europe, and help balance its engagement with Russia.

These views were echoed by retired Turkish ambassadors Ünal Çeviköz and Mehmet Fatih Ceylan,5 who in interviews emphasized an open border and diversified connectivity as strategic priorities for Turkey. Ceylan further argued that deeper regional connectivity is vital for Turkey to attract European investment in infrastructure projects, as Turkey’s own economic resources are insufficient for these initiatives.

Diversification would also be a strategic gain for Ankara given the dramatic pivot away from Europe in Georgia’s foreign policy and the country’s democratic decline. The continued political crisis in Tbilisi highlights the strategic risks for Turkey of relying on Georgia as its single access point to the Middle Corridor, a trade route that connects Europe to China. Equally important, greater connectivity would offer Turkey a framework to engage with the South Caucasus regionally, rather than relying solely on bilateral ties. Enhanced infrastructure links also strengthen the prospects of modernization and the normalization of regional politics—both necessary conditions for middle powers to expand their global influence.

Engagement between Armenia and Azerbaijan, particularly in the lead-up to the Washington summit, has lacked key features of effective peace processes, such as demilitarized zones, third-party guarantees, and joint commissions. In the fragile postwar period after 2020, Ankara’s policies did little to strengthen peace dynamics, instead disproportionately favoring Baku. As a result, Azerbaijan both slowed down the peace process and curtailed Turkey’s ability to position itself as a middle power in the South Caucasus or raise its standing in world politics.

As analyst Laurence Broers has noted in 2021, Turkey remains a “partisan patron” in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, despite having the potential to be a peacemaker. In 2020, Ankara’s decisive military and political support for Azerbaijan reinforced a geopolitics of war rather than of peace. This intervention further weakened the already fragile multilateral framework of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Minsk Group, which was rooted in liberal principles of rights, representation, and inclusivity. Broers described this situation as a “requiem for the unipolar moment in Nagorny Karabakh,” highlighting Turkey’s effort to shift diplomacy away from multilateralism toward coercive, militarized bargaining, and authoritarian conflict management, in which minority rights are securitized.

For Turkey to cut the Gordian knot in the South Caucasus, it would need to shift from partisan patron to peacemaker. This would mean denying Aliyev veto power over Ankara’s regional policies by delinking Turkey’s relations with Armenia from the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process. Such a shift would diversify Ankara’s engagement in the South Caucasus by expanding trade and transit routes while strengthening the diplomatic frameworks necessary to sustain them. In short, a strategy of three Ds—deny, delink, and diversify—could elevate Turkey’s role and capabilities as a middle power in the region and beyond.

This 3D strategy would enable Turkey to shape the regional order, enhance its position as a continental connectivity hub, and create new sources of leverage relative to Russia, China, and Europe. Given the Israel-Iran conflict, the strategic value of regional stability in the South Caucasus will only increase for Ankara. Just as importantly, stability would catalyze regional transformation by fostering connectivity and reducing trade and transit distortions. Such a transformation is also necessary, although not sufficient, for the durability of the peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Turkey’s transition from partisan patron to peacemaker requires proactive regional diplomacy. Despite its militarized and personalized approach to the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, Turkey has significant capacity to transform the broader regional context and consolidate the peace process. In this light, the 3D policy could generate concrete peace dividends by shifting the structural environment of the conflict. A Turkey-Armenia rapprochement and a reopened border for trade and tourism would create new stakeholders in peace and stability across the South Caucasus by allowing regional supply chains and broader societal ties to emerge.

There are a few pathways for Turkey to transform and expand its role in the South Caucasus. The first step is to reconsider the strategic value of armed conflict versus deep diplomacy and institutionalized cooperation in the region. A government official, speaking on the condition of anonymity, articulated a vision for Turkey in which “the [Western] Balkans and the South Caucasus” are the two wings needed for the Turkish eagle to soar. With the Middle East mired in cyclical violence, Turkey’s chances of developing as a middle power will remain limited without enduring regional stability in the South Caucasus.

Almost all correspondents in Turkey—retired diplomats and academics—pointed out that being surrounded by regions of conflict can reduce the power of middle states. Indeed, Russia’s strategy of using regional fracture on its periphery to project power globally has shown its limits: Fractured regions around middle powers are not only short-term levers but also long-term liabilities.

If Turkey reverts to its old playbook, it may push for only partial implementation of the Washington agreement: securing new routes to Azerbaijan while keeping its border with Armenia closed and denying Yerevan reciprocal access to Europe. Such a strategy would privilege Azerbaijan and yield short-term political gains for Erdoğan, but it would ultimately undermine Turkey’s broader continental interests.

Indeed, the ink is barely dry on the Washington deal, yet Aliyev appears to be testing the boundaries of the peace process he has publicly endorsed. His call for constitutional changes in Armenia introduces complexities that could affect the country’s domestic political landscape ahead of its 2026 parliamentary election. While open, democratic debate on the agreement can strengthen its legitimacy, it also carries political risks for pro-peace and pro-democracy forces. In October 2025, Baku lifted its restrictions on cargo transit to Armenia, allowing Kazakh wheat to reach the country—a step that may signal an effort to advance the peace agenda or to weaken Russia’s regional influence, given its dominance of wheat imports into Armenia. The former is a prerequisite for achieving the latter.

What is more, Aliyev continues to invoke the term “Zangezur Corridor” rather than TRIPP—a designation he formally accepted during the meeting in Washington. This framing contradicts the rules-based international order that the summit sought to reinforce. The fact that Turkish officials also employ the corridor terminology suggests that Baku and Ankara may be reverting to a revisionist tool kit in their regional engagement.

For Aliyev, this language preserves strategic ambiguity in Azerbaijan’s dealings with Armenia. For Ankara, however, persisting with this approach risks generating long-term strategic losses by narrowing Turkey’s role to that of a partisan actor. A more forward-looking pathway would be for Turkey to assume normative and institutional leadership, position itself as a driver of regional connectivity, and enhance its credibility as a Eurasian middle power.

Turkey, like other effective middle powers, can exercise normative leadership in the South Caucasus by supporting and regionalizing the international norms of territorial integrity and nonaggression. Ankara has consistently backed Georgia’s territorial integrity and supported Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict under the same doctrine. Turkey has recognized Armenia’s independence and avoided recognizing breakaway regions like Abkhazia.

However, Ankara’s normative stance has been uneven—especially when it comes to aggression. Turkey backed Azerbaijan’s use of force in 2020, undermining an already fragile peace process. Ankara remains ambiguous amid Baku’s revisionist rhetoric and military actions inside Armenian territory, raising concerns among diplomats and analysts. As Coşkun has noted, Turkey must clearly reiterate its commitment to sovereignty and territorial integrity to serve as a credible peace broker.

The Washington agreement, as a partial peace settlement, bodes well for an eventual Armenia-Azerbaijan peace treaty. Data published in 2016 on partial peace agreements show that they increase the chances of comprehensive peace accords in the future and contribute to their successful implementation. By advancing a norms-based framework, Washington exercised normative leadership, leaving Turkey in a position of having to catch up. At a minimum, Ankara should avoid adopting Aliyev’s revisionist terminology of the “Zangezur Corridor,” which generated a critical reaction from Yerevan.

Turkey can also exercise institutional leadership in the region. The Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process is unfolding in a fragmented region that lacks institutional frameworks of regional politics and governance. Turkey has an opportunity to promote open regionalism in the form of regional trade and cooperation frameworks that reduce economic distortions, create tools for region-wide solutions to global problems, establish regional stability as a public good, and build trust among historic rivals. Past efforts, such as the Caucasus Stability Pact or the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, have had limited impact. Delinking the search for an Armenia-Azerbaijan peace agreement from Turkey’s relations with Armenia is an easy opportunity for Ankara. This would unlock new opportunities for EU-backed regional formats in the South Caucasus, much like EU-Turkey cooperation in the Western Balkans after the 1995 Dayton Accords.

In addition, Ankara can champion infrastructure connectivity in the South Caucasus. Turkey’s geographic position gives it leverage to become a regional transit and energy hub—a policy goal that Ankara has announced it is pursuing. However, its current strategy risks playing into Azerbaijan’s corridor approach, which has worsened trade inefficiencies and threatens to drag the South Caucasus into a contestation of the rules-based global order. The Washington agreement was a pushback against the logic of an extraterritorial corridor, as pursued by Baku. But unless the agreement’s principle of reciprocity is matched by synchronized improvements in transit for both Armenia and Azerbaijan, Washington will be unable to achieve an open South Caucasus.

Turkey could champion integrated connectivity projects aligned with international norms and thus emerge as a major implementing actor for the Washington agreement. Ankara is already falling behind when it comes to diplomatic initiatives for Eurasian connectivity. The EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure investment initiative and Black Sea Synergy project are expanding in Central Asia and the South Caucasus with little Turkish involvement. Despite Turkey’s rhetorical solidarity with other Turkic states, its influence in Central Asia remains limited.

In sum, Turkey’s uneven commitment to norms, limited institutional initiative, and reactive diplomacy threaten to marginalize its role in shaping the postconflict regional order in the South Caucasus. By fully embracing its status as a middle power—grounded in norms, institutions, and connectivity—Turkey could realize its strategic potential as a Eurasian bridge between East and West.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

A prophetic Romanian novel about a town at the mouth of the Danube carries a warning: Europe decays when it stops looking outward. In a world of increasing insularity, the EU should heed its warning.

Thomas de Waal

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

Local political and social dynamics will shape the implementation of any peace settlement following Russia’s war against Ukraine—dynamics that adversaries may seek to exploit.

Daryna Dvornichenko, Holger Nehring