This piece is part of a Carnegie series examining the impacts of Trump’s first 100 days in office.

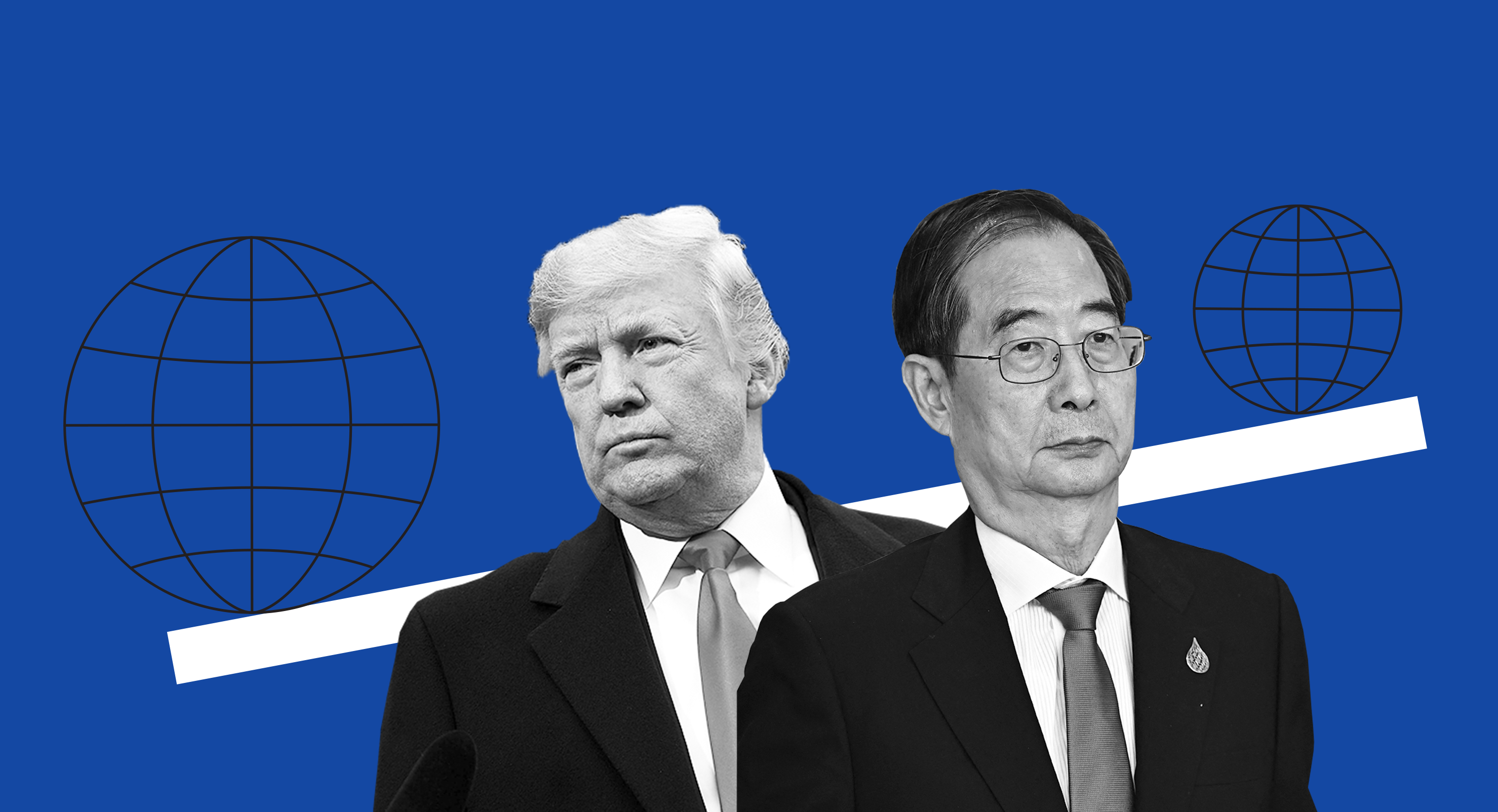

As President Donald Trump returns to the White House with a more assertive and transactional foreign policy agenda, South Korea faces renewed pressure to navigate its structurally lopsided alliance with the United States. The alliance remains foundational to Korea’s security and economic positioning, yet Trump’s second term has revived familiar anxieties.

These concerns echo unresolved tensions from Trump’s first term but now intersect with a more fragmented international order on top of deepening political uncertainty in Seoul following President Yoon Suk-yeol’s impeachment. The challenge for Korean leaders is not whether the alliance still matters to its national strategy—it does—but how to manage the “quiet crisis” when the senior partner appears increasingly willing to rewrite the rules.

Korea’s polarized political landscape and absence of a president only sharpen these anxieties. Although conservatives emphasize alignment with Washington and progressives traditionally advocate for more autonomy, no camp offers clear answers for an alliance increasingly shaped by Trump’s preference for going it alone. Even opposition frontrunner Lee Jae-myung, faced with the reality of Trump’s transactional approach to alliances, has tempered past progressive skepticism in favor of a more centrist, U.S.-friendly tone. What unites this fractured moment is a growing unease: how to protect national interests when the alliance’s reliability is no longer a given.

Korea’s alliance anxieties are roughly grouped into two categories: economic and security. First, Trump’s revived economic nationalism has once again placed South Korea’s industrial and trade policies under scrutiny. The administration’s sweeping tariffs—including a 25 percent duty on Korean goods—ignore Seoul’s longstanding contributions to the American economy and rebuilding the industrial base. But Trump’s singular focus on trade balances has little patience for such nuance, and Korea’s $66 billion trade surplus remains a target.

This blend of hedging and alliance maintenance in the economic domain reflects Seoul’s broader strategy of pragmatic calibration—navigating great power competition without being forced into binary choices. After a trilateral trade ministers meeting at the end of March, Chinese state media claimed Beijing, Tokyo, and Seoul would coordinate a response to U.S. tariffs—an assertion both Japanese and South Korean governments swiftly denied. The episode nonetheless underscores a deeper reality: both South Korea and Japan face structural dependencies on the United States and commercial imperatives to shift production from China—realities that shape a latent, calculated strategy of regional hedging.

In anticipation of sweeping tariff measures following Trump’s inauguration, Korean conglomerates stepped in as de facto economic ambassadors. Their approach aims to lock in the economic leg of the alliance through job creation and technological interdependence. Underscoring this strategy, a high-level Korean business delegation visited the White House in February to secure expedited approvals and regulatory relief for their continued investment in America’s manufacturing base. But the visit revealed the limits of private-sector diplomacy under the current administration’s investment threshold and new requests for more billion-dollar investments. The Trump administration may already see its broad tariff strategy paying off, with Korean officials visiting Washington in April to sign a trade agreement. Whether this will supplement or replace the existing 2012 bilateral free trade agreement, which the first Trump administration renegotiated in 2017, is unclear.

On the security side, Korean officials worry that the country may again be sidelined from high-stakes diplomacy over North Korea’s nuclear program. During his first term, Trump relied on President Moon Jae-in to serve as a diplomatic conduit in brokering first contact with Pyongyang. In his second term, Trump brings an established rapport with North Korea leader Kim Jong-un and may have less incentive to coordinate with Seoul. This is especially worrisome for Seoul if the White House pivots away from Ukraine and turns its attention back to the Korean Peninsula in the quest for a Nobel Peace Prize. Washington could pursue direct negotiations with Pyongyang that leave Seoul with few tools to influence outcomes that carry serious consequences for its national security and sovereign mandate to unify the peninsula.

But an even deeper concern is structural: Would a Trump administration truly come to Korea’s defense in a conflict with the North? Amid doubts about U.S. commitments to NATO and Ukraine, South Koreans are watching closely Trump’s negotiations with Russia. The result in Seoul has been a reanimation of domestic debates over nuclear self-reliance. Polls show strong public support for a domestic nuclear option—whether redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons or pursuit of their own indigenous capability, contra Seoul’s NPT obligations. The full cost of the political and financial risks may be underestimated in Korea, and many proponents of the nuclear option in Seoul believe Trump might carve out exceptions for South Korea. While the Yoon administration had tempered these discussions through mechanisms such as the Nuclear Consultative Group with the Biden administration in 2023, the debate remains far from settled among Korean strategic thinkers and politicians.

Despite the headwinds, South Korea still holds leverage—especially in areas vital to the Trump administration’s longer-term strategic priorities. The entanglement of Korean industry with U.S. economic security—including in critical technologies like semiconductors and advanced batteries—makes Seoul a key player in Washington’s effort to decouple from Chinese supply chains.

Korea’s geostrategic position also remains central to any Indo-Pacific strategy aimed at countering China—an area expected to regain focus if and when U.S. attention shifts from prolonged conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine. Trump may be skeptical of traditional alliance frameworks, but he cannot fully dispense with them if he hopes to contain Beijing. This gives Seoul room to maneuver, even in a transactional environment.

The current leadership vacuum in Seoul may even buy Korea time. Domestic backlash to Trump’s tariff agenda—including manufacturers and lawmakers in Korean-invested districts—may already be tempering the administration’s hardline stance. Meanwhile, Trump may be constrained on a North Korea deal by Pyongyang’s lingering resentment over the 2019 meeting in Hanoi and Kim’s strategic entanglements with Moscow. This dynamic could delay any immediate reengagement, buying Seoul space to recalibrate its own approach to peninsular security as part of an updated alliance strategy once a president is elected.

In this uncertain moment, South Korea is demonstrating the art of alliance management under asymmetry: hedging carefully, investing strategically, and betting that even a stronger ally cannot afford to abandon its most deeply enmeshed partners.

Read more from this series, including: