Two weeks after parties to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) concluded their five-year Review Conference in New York, the main decision-making body of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) meets in Vienna starting today. On the agenda are ongoing IAEA investigations in Iran and Syria, Israel’s nuclear capability, and the IAEA budget.

In a Q&A, Mark Hibbs writes that it is unlikely that a dramatic showdown with Iran or Syria will occur during the meeting. And while there may be heated exchanges over Israel’s program, there is little chance it will lead to any action from the IAEA.

- What is the importance of the IAEA Board of Governors meeting in Vienna? Is there a connection between the board meeting and the 2010 NPT Review Conference which was concluded at the end of last month?

- With a recently announced deal to ship some of Iran’s low-enriched uranium to Turkey and movement toward international sanctions against Iran, how will Iran’s nuclear program be dealt with during the board meeting?

- Is the IAEA’s investigation of Syria’s nuclear activities proceeding smoothly and will the board move forward on this issue?

- Was the discussion of Israel’s nuclear activities at the board this month prompted by the NPT Review Conference?

- Are there any other issues that will be considered at the board meeting?

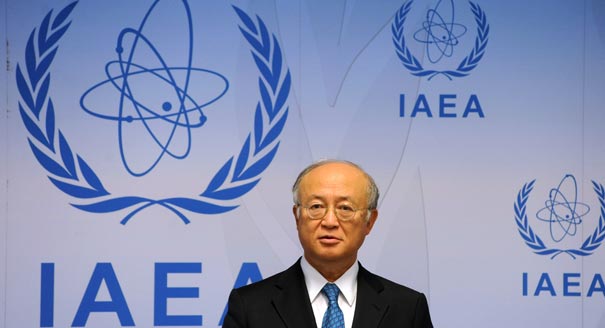

- How do board members view Yukiya Amano’s leadership six months after succeeding Mohammed ElBaradei as head of the UN's nuclear agency?

What is the importance of the IAEA Board of Governors meeting in Vienna? Is there a connection between the board meeting and the 2010 NPT Review Conference which was concluded at the end of last month?

The IAEA Board of Governors, consisting of 35 of the IAEA’s 151 member states, meets routinely four times a year. The board meeting and the IAEA General Conference, which convenes annually in September, are the IAEA’s two main decision making bodies. Beginning on June 7 and expected to last three days or more, the board meeting is a routine quarterly meeting. As is usually the case for the annual June conclave, the agenda includes the IAEA’s annual budget. Likewise, as has been the case for the last several years, board members next week will also concern themselves with ongoing IAEA verification flashpoints in Iran, North Korea, and Syria—all countries under investigation by the IAEA for their nuclear activities.

Nearly all IAEA members are parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Last week in New York, most of the NPT’s 189 members met to review the treaty (a meeting held once every five years). For the first time since 2000, the NPT Review Conference adopted a consensus final document acceptable to all parties. That outcome was in doubt until the final moments of the Review Conference because of a divide between the United States and many other states over Israel’s nuclear capability. In the end the United States compromised, permitting the conference to expressly urge Israel—one of three states with nuclear weapons outside the NPT—to join the treaty and put all its nuclear facilities under IAEA safeguards. This week, and for the first time since 1992, the same topic will be on the agenda of an IAEA board meeting. That is, formally speaking, a coincidence, but it also reflects greater urgency by the 118 mainly developing countries that form the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) to make progress toward the elimination of nuclear weapons in the Middle East.

With a recently announced deal to ship some of Iran’s low-enriched uranium to Turkey and movement toward international sanctions against Iran, how will Iran’s nuclear program be dealt with during the board meeting?

Since the last IAEA board meeting in March, Iran continues to impede the IAEA in critical areas. Tehran has not provided design information for a nuclear power plant, heavy water reactor, or new enrichment facilities. Iran is also continuing to ignore the United Nations Security Council sanctions and previous IAEA board resolutions. Nor has Iran addressed allegations, compiled in a dossier by the IAEA Department of Safeguards, suggesting that Iran secretly engaged in research and development for a nuclear weapon beginning in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq war.

While underscoring that the IAEA has not concluded that Iran diverted any of the enriched uranium it is producing at declared facilities, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano reported this lack of cooperation by Iran to the board on May 31. Regardless of Amano’s unfavorable conclusions on Iran, Western diplomats said at the conclusion of the NPT Review Conference that they did not expect a dramatic showdown with Iran during the coming board meeting.

The IAEA board includes both Brazil and Turkey, which last month announced they had reached a breakthrough with Iran to supply fuel enriched to 20 percent for a research reactor in Tehran in exchange for Iran sending a portion of its domestically-processed enriched uranium to Turkey. The United States and some of its allies are critical of this deal, and for financial, legal, technical, or logistical reasons it may turn out to be impractical. Still, neither Brazil or Turkey want to see a confrontation between the United States and Iran in the boardroom get out of hand and they will work with NAM states to try to ensure that the meeting ends without escalating the crisis.

The Brazil-Turkey-Iran arrangement was concluded at a time when the European Union is trying to coax Iran to hold more talks on its nuclear program with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany (P5+1). The P5+1 have pressed Iran in vain to give up its uranium enrichment program since 2003. Due to the EU’s ongoing efforts, the United States could try to avoid escalating a confrontation with Iran at the board meeting this month.

But the one factor that could change the outcome of IAEA board deliberations on Iran this week is the timing of the P5+1-led sanctions against Iran. Following a recent announcement by Secretary Clinton that major powers, including China and Russia, agreed to a draft Security Council resolution for a fourth set of sanctions on Iran, some European states urged the United States to slow down the sanctions drive late last month. The United States also anticipates a request from one P5 state—China—and perhaps from another—Russia—to delay sanctions against Iran on the basis of the Brazil-Turkey-Iran gambit.

Were sanctions to come to a vote at the Security Council this week, that debate could spill over into the board meeting deliberations. But at the outset of the board meeting, P5+1 diplomats in Vienna have indicated, in recent days, Russia had stood in the way of moving quickly on sanctions at the Security Council. This means it is more likely that the sanctions issue will be brought to the Security Council during the week of June 14, not before.

Regardless of the status of the UN sanctions, Western diplomats said they expected Iran would arrive in Vienna prepared to do battle with P5 board members.

Is the IAEA’s investigation of Syria’s nuclear activities proceeding smoothly and will the board move forward on this issue?

As in the case of Iran, it is not anticipated that the board will take any decisive action this month regarding the IAEA’s ongoing investigation into Syria’s nuclear activities. For over two years, the IAEA has failed to reach a conclusion about allegations raised by the United States and Israel concerning a site Israeli aircrafts bombed in Syria in 2007. Both countries assert that the facility was a clandestine plutonium production reactor built with North Korean assistance.

In principle, the United States supports the idea of the IAEA requesting a so-called “special inspection” in Syria, as the IAEA is empowered to do under its safeguards agreement with that country. If requested, that inspection would be designed to look at a few sites which the United States asserts, based on intelligence data, point to clandestine nuclear fuel cycle cooperation—for plutonium separation or uranium fuel production—between Syria and North Korea.

But neither the United States, nor a majority of board member countries, nor Amano himself is inclined to press for a special inspection in Syria at this time. The United States is in no hurry to call for a special inspection because, in its view, the Israeli attack destroyed the reactor and because the fuel cycle cooperation between Syria and North Korea at the sites identified by U.S. intelligence in Syria was at an early stage when the work was interrupted in 2007.

For political reasons the United States might even be inclined to accept that the IAEA’s Syria probe is never decisively concluded, but some other Western board members, in particular European states, are becoming impatient with the IAEA’s lack of progress in reaching closure on this issue

Some officials from these states believe that a failure to reach firm conclusions on Syria will damage the IAEA’s credibility under Amano, especially since he has already informed the board that, on essential matters, Syria has not cooperated with the IAEA. Some board members may therefore want to see the IAEA request a special inspection later in 2010. But so far, there is not enough political will—either at the top of the IAEA secretariat or in the board—to press Syria for a special inspection.

Was the discussion of Israel’s nuclear activities at the board this month prompted by the NPT Review Conference?

No. Last September, the IAEA General Conference passed a resolution by a narrow majority of member states—49 in favor, 45 against, and 16 abstaining—calling upon Israel “to accede to the NPT and place all its nuclear facilities under comprehensive IAEA safeguards.” That resolution also requested that Amano report to the board and the General Conference on this matter in 2010. Amano earlier this year sent letters to each member state asking for input and comment concerning this issue. A small number of states replied. The board will likely take note of Amano’s actions in response to the 2009 General Conference resolution but the issue of Israel’s nuclear capabilities will not likely lead to any forward motion in the boardroom.

We can expect some polemical exchanges during the meeting between Israel and the United States, on the one hand, and some Middle Eastern and NAM states, including Iran, on the other. Palestine will likely attend and address the board meeting as an observer.

Had the United States not dropped its long-reiterated objection to naming Israel in the final document (which urged Israel to join the NPT as a non-nuclear weapons state) on the last day of the NPT Review Conference, it is likely that the rhetoric at the June board meeting would be more acrimonious, possibly interfering with the conclusion of its agenda items.

Are there any other issues that will be considered at the board meeting?

One important item on the agenda of the meeting is the IAEA budget for the coming year, routinely passed annually during June board sessions. This year, the IAEA secretariat, supported by some advanced nuclear states led by the United States, wants an appropriation of 26 million euros to pay for an upgrading of equipment and facilities at the IAEA’s safeguards laboratory at Seibersdorf, Austria.

In recent years, the majority of NAM states—which constitute a majority at the IAEA General Conference but not on the IAEA board of governors—has been cool to additional spending on safeguards and other nonproliferation and nuclear security-related programs. But this month, NAM countries will be joined by a group of advanced Western states—chief of which are Canada, Germany, and Switzerland—which during the last decade have urged the IAEA to cut costs. Prior to and right up to the beginning of the board meeting on June 7, the IAEA secretariat three times failed to convince member states to support its request for the safeguards lab funding.

How do board members view Yukiya Amano’s leadership six months after succeeding Mohammed ElBaradei as head of the UN's nuclear agency?

Amano was warmly welcomed by Western advanced nuclear states in the interest of a more technical and circumscribed vision of the IAEA than what was increasingly advocated by ElBaradei during his 12 years as head of the agency. But Amano was firmly opposed by most NAM members, who believed he would heed the interests of advanced countries, and he was elected by a one-vote majority. Even before taking office and especially since then, Amano has held a raft of meetings with NAM states and he has stressed during these meetings that one of his highest priorities as director general will be to repair the breach which opened up between the NAM and the advanced Western states during the second half of ElBaradei’s tenure.

Amano has also highlighted technical cooperation programs at the IAEA in the field of medicine in an effort to improve relations with the NAM. Some advanced Western states are concerned that Amano may be bending too far to accommodate the NAM and officials from these countries suggest that their governments may lose patience if Amano does not firmly support some key issues they favor. One of these is an initiative, originally launched by ElBaradei, to establish multilateral nuclear fuel cycle centers. This is now advocated by the United States, Japan, Russia, and European states, but it may be shelved by Amano for as long as one to two years out of concern for the sensitivities of developing countries, which fear that the project is intended to blunt their nuclear industry development.

Western states are also concerned about upcoming appointments which Amano will make, in particular for deputy director generalships in critical areas such as technical cooperation and nuclear applications, and for a senior position in the field of nuclear security. The NAM states are pressing Amano to appoint NAM country officials to three deputy directorships during his four-year tenure.

At the same time, leaders from Western states seem to understand that the lack of consensus between Western states and NAM states is deep-rooted and that Amano will need a lot of time and support to regenerate an atmosphere of mutual trust. Western states so far are also encouraged by a few key personnel decisions taken by Amano as director general, and they are satisfied by Amano’s resolve to “fully implement” safeguards agreements in member states, most notably in Iran.