Having failed to build a team that he can fully trust or establish strong state institutions, Mirziyoyev has become reliant on his family.

Galiya Ibragimova

{

"authors": [

"Marwan Muasher"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Arab Awakening"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"North Africa",

"Egypt",

"Gulf",

"Levant",

"Maghreb"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Democracy"

]

}

Source: Getty

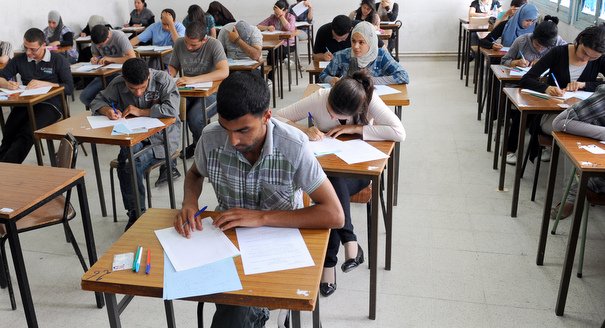

Domestic and international attention is focused on elections and written constitutions in the Arab world, but democratic structures won’t thrive until education is reformed to teach free thinking, respect for other people's opinions, and citizenship.

Source: National Interest

Traditionally, Arab education systems have been about control. Schools teach obedience to the regime instead of problem solving, critical thinking and freedom of expression. Students don't learn about political rights and are taught not to question authority.

Textbooks in Egypt emphasize tourist attractions much more than political participation, and it's easier to find the word "authority" than "citizen." In Jordan, reform initiatives in schools pay no attention to the need for people to become active in civil and civic society.

But democracies need open societies with cultures that embrace diversity, accept conflicting opinions, tolerate dissent and recognize that not all truths are absolute. Only with this kind of thinking will the necessary checks and balances in a democracy work.

While Arab countries have invested heavily in education, spending an average of 5 percent of GDP annually over the past forty years, the results are unimpressive. And the challenge is pressing. One in three people across the region are under the age of fifteen, and 70 percent of the population is under thirty.

Current reform efforts, where they exist, don't come close to fixing the problem. They are focused largely on building new schools, purchasing more computers, increasing enrollment rates and boosting test scores. While important, these improvements are not enough.

Better results have therefore not followed reforms. There are no tangible changes in teaching methods, and test scores remain low in reading, math and science. After recent educational changes were introduced in Tunisia, the average test scores of fourth graders actually fell between 2003 and 2007. And in Egypt, eighth graders' scores dropped in both math and science in the same period.

That suggests reforms should focus on the human factors. Students should learn how to think, question and innovate at a young age. This is what it takes in a competitive global economy.

The Arab world also needs more highly skilled teachers and classroom environments more conducive to learning. Teaching remains mostly didactic and lecture based, emphasizing rote memorization of facts. This doesn't provide for open discussion and active learning.

The kind of educational reform that empowers citizens is resisted, however, by an unspoken alliance between governments and religious institutions, which want to maintain their monopoly over school curricula and practices. Status-quo forces see independent, creative and well-educated students as threatening. Until this changes, democratic hopes will suffer.

Arab democracy isn’t likely to succeed without educational reforms. And yet serious reform efforts are conspicuously hard to find in the Arab world. It will take time to revamp schooling and instill values from the beginning of children's education. But that is the only way to prepare the ground for real change.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Having failed to build a team that he can fully trust or establish strong state institutions, Mirziyoyev has become reliant on his family.

Galiya Ibragimova

A prophetic Romanian novel about a town at the mouth of the Danube carries a warning: Europe decays when it stops looking outward. In a world of increasing insularity, the EU should heed its warning.

Thomas de Waal

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes