C. Raja Mohan, Darshana M. Baruah

{

"authors": [

"C. Raja Mohan"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie India"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie India",

"programAffiliation": "SAP",

"programs": [

"South Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"South Asia",

"India"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Trade",

"Security",

"Military",

"Foreign Policy",

"Nuclear Policy"

]

}

Source: Getty

Finish What You Started

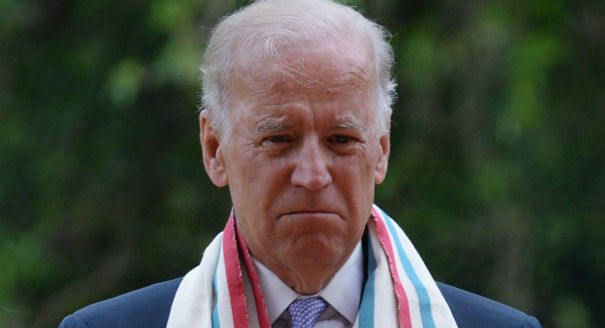

Vice President Joe Biden’s strong record on U.S.-Indian relations raises hopes for his visit to New Delhi.

Source: Indian Express

It is not often that American vice presidents show up in India. In any case, vice presidential visits abroad don't get too much attention either in the United States, or the host country. But there are good reasons to take U.S. Vice President Joe Biden's visit this week to Delhi and Mumbai seriously. U.S. vice presidents are no longer inconsequential in the making of American domestic and foreign policies. Biden's two predecessors, Dick Cheney and Al Gore, had considerable influence in defining the national agenda during the George W. Bush and Bill Clinton administrations respectively.

Biden enjoys the full confidence of President Barack Obama, who has cut much political space for his vice president. Biden played a key role in contributing to Obama's victory in both the presidential campaigns. Folksy and combative, Biden was a valuable foil to Obama, who tends to be professorial and finds it difficult to connect with ordinary people. Biden's vast international experience has often come in handy for Obama in coping with the major foreign policy challenges that he inherited from Bush in Iraq and Afghanistan. Biden's pragmatism has helped cut through the arguments of the ideologues on the left and right, who tend to dominate the foreign policy discourse in Washington.One hopes Biden will bring the same common sense to bear upon India-U.S. relations, widely perceived to be in a trough. Biden was among the key people in Washington who helped transform the India-U.S. relationship over the last decade. The Democratic Party's foreign policy establishment reacted vehemently against the historic civil nuclear initiative unveiled by former President Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh eight years ago this month. Hillary Clinton, then in the race for the presidency, chose to stay quiet. Obama, a freshman senator who was finding a niche for himself, was critical of the deal and demanded changes. In contrast, Biden eagerly embraced the civil nuclear initiative, helped reduce the suspicions among the Democrats and ensured its passage in the U.S. Congress twice over. Few political leaders in the Democratic Party can claim ownership of the civil nuclear initiative in the manner that Biden can. The vice president, however, comes to India at a time when there is a sense of drift in India-U.S. relations. His principal task would be to find ways to impart new momentum to them.

Although the India-U.S. engagement has expanded and deepened beyond anyone's imagination over the last decade, there is no hiding the disappointments on both sides. Some would say India and the U.S. are simply moving from an extended honeymoon to the challenges of making a marriage work. The romance has inevitably yielded to a tiresome routine. Staying with the metaphor of marriage, Biden and his Indian interlocutors must focus on five guidelines to make the relationship robust and enduring.

First, renew the political vows. Former President Bush and then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee were not just animated by a narrow strategic calculus when they chose to define a new direction for bilateral relations. They were moved by a strong conviction that after five wasted decades, Washington and Delhi could and should be natural partners. The initial vision that drove the partnership has been lost with bureaucracies on both sides slowing the momentum. All partnerships require mutual faith, and restoring it should be at the top of the agenda in the conversations between Biden and the Indian leadership.

Second, remember the shared long-term interests. Delhi and Washington need each other a lot more today than a decade ago, whether it is in accelerating economic growth or promoting national security. America's unipolar moment has passed, and the expectations about India's rapid economic growth have dimmed. Delhi and Washington help themselves by deepening the partnership with the other.

Third, finish what you started. The time has come for the political leadership in both capitals to emphasize the importance of completing the ambitious agenda unveiled in 2005. Delhi and Washington must quickly iron out the remaining wrinkles in the implementation of the civil nuclear initiative, facilitate commercial agreements between American vendors and Indian operators, and intensify the effort to complete India's integration into the global order. On the defense front, Washington must keep its word on liberalizing technology transfer. In turn, Delhi must make it easier for U.S. defense and high technology companies to invest in India.

Fourth, don't be too transactional. All good relationships are based on give and take. But they can't be sustained on the basis of constant accounting of what has been delivered by the other side. Exaggerated notions of what one or the other owes, leads to recrimination, bad blood and separation. Delhi and Washington can't allow the India-U.S. partnership to become a nickel and dime operation, with senior figures in both capitals obsessing about the trivia and forgetting the big picture.

Five, intensify strategic cooperation in Asia. During the Cold War, the central problem for India and the U.S. was their conflicting approaches towards Asia. The improvement of the bilateral relationship in the last few years has been rooted in greater convergence of their interests in Asia.

As Delhi and Washington try to develop separate, special relationships with Beijing, there is a danger of misreading each other's intentions. Both India and the U.S. want a secure Afghanistan and moderate Pakistan, but their approaches are not always in sync. An honest conversation between Biden and the Indian leaders on the changing regional balance is critical at this juncture to prevent misperceptions from derailing India-U.S. security cooperation in Asia.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Senior Fellow, Carnegie India

A leading analyst of India’s foreign policy, Mohan is also an expert on South Asian security, great-power relations in Asia, and arms control.

- Deepening the India-France Maritime PartnershipArticle

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization at Crossroads: Views From Moscow, Beijing and New DelhiCommentary

- +1

Alexander Gabuev, Paul Haenle, C. Raja Mohan, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Duqm at the Crossroads: Oman’s Strategic Port and Its Role in Vision 2040Commentary

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Lessons Learned from the Biden Administration’s Initial Efforts on Climate MigrationArticle

In 2021, the U.S. government began to consider how to address climate migration. The outcomes of that process offer useful takeaways for other governments.

Jennifer DeCesaro

- India Signs the Pax Silica—A Counter to Pax Sinica?Commentary

On the last day of the India AI Impact Summit, India signed Pax Silica, a U.S.-led declaration seemingly focused on semiconductors. While India’s accession to the same was not entirely unforeseen, becoming a signatory nation this quickly was not on the cards either.

Konark Bhandari