Alexander Gabuev

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Gabuev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"Eurasia in Transition"

],

"regions": [

"East Asia",

"China",

"Central Asia",

"Russia"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Trade",

"Foreign Policy",

"Global Governance"

]

}

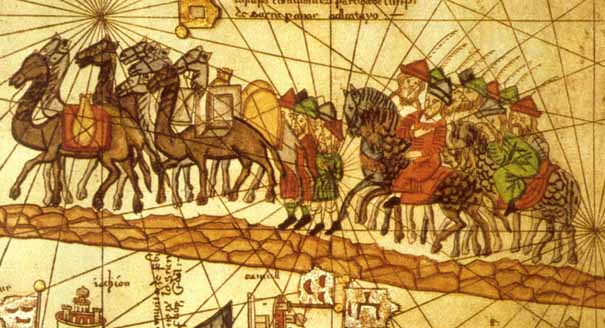

Source: Getty

Another BRIC(S) in the Great Wall

Vladimir Putin will likely see the BRICS summit as proof that the West’s attempts to isolate Russia have failed. However, Russia’s growing fascination with the BRICS and the SCO coincides with diminishing Chinese interest in both projects.

This week, the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa will gather for the seventh annual BRICS summit in Ufa, a city in Russia’s Ural Mountains at the geographical heart of Eurasia. The BRICS’s leaders will be joined by the heads of state of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states.

Standing next to Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Russian President Vladimir Putin will likely see the summit as proof that the West’s attempts to isolate Russia have failed, that the Russian president is surrounded by powerful and likeminded friends.

In addition to gaining international prestige, the Kremlin expects to reap tangible economic rewards from the summit through two potentially transformative geopolitical projects: the creation of the BRICS-backed, $100-billion New Development Bank and $100-billion Currency Reserve Pool; and the reinvigoration of the SCO, aimed at improving Russian-Chinese cooperation in Central Asia.

The only problem in this calculation is that Russia’s growing fascination with the BRICS and SCO coincides with diminishing Chinese interest in both projects, as Beijing turns its focus to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative (a framework for economic development with Eurasia).

The grandiose gathering in Ufa marks the second time that the SCO and BRICS summits have coincided in Russia. In 2009, then president Dmitry Medvedev welcomed the Brazilian, Indian, and Chinese leaders to attend the first BRIC summit, held alongside the annual SCO meeting. The international backdrop against which the 2009 summits were held resembled current geopolitical situation: the meetings took place in the aftermath of the August 2008 Russo-Georgian War; Moscow was facing increasing isolation in the West, with high-level meetings like the Russia-EU and Russia-NATO summits having been cancelled. Like the 2009 meetings, the 2015 summits are meant to present an alternative to the West-dominated global order.

But hosting the BRICS and SCO summits is even more important for Russia now than it was in 2009. Facing growing pressure from the West because of its role in the Ukraine crisis, Moscow is desperate to show that attempts to isolate Russia are doomed to fail, and that the country still has many powerful and loyal friends. The gathering combines two narratives, which have become dominant in Russian foreign policy: that Russia is a leading non-Western power aiming to build a truly multipolar world, and that Eurasia is a new center of economic and political gravity, where Russia and China can peacefully cooperate without U.S. interference.

In Moscow’s eyes, the BRICS summit will help pave the way to a new international financial order not dominated by the West. The SCO summit will mark the beginning of Pakistan’s and India’s accession processes (to be completed in 2016), thereby demonstrating the SCO’s vitality and global attractiveness. Moreover, the SCO will provide a platform for linking Russia’s and China’s major geopolitical projects in Eurasia, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the OBOR initiative, as envisaged in joint statement signed by Putin and Xi in Moscow on May 8.

While China may provide moral support to Russia by endorsing Moscow’s role in a multipolar world, it is pragmatism not sentimentality that brings Beijing to Ufa. Indeed, Although Moscow and Beijing have grown closer in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, China will not necessary give into Russian ambitions in the SCO and BRICS institutions. Beijing sees the BRICS as one of many vehicles to elevate China to the status of financial superpower. It also uses the club as a platform through which it can present its ambitions for a bigger role in the global financial architecture; indeed, the New Development Bank and Currency Reserve Pool will be useful instruments for promotion of the RMB.

The BRICS also offer China a forum at which it can think about alternatives to the West-driven global order it aims to create, where it can brainstorm with like-minded powers, exchanging—and sometimes borrowing—ideas. The AIIB is one of the outcomes of this brainstorming. Many U.S. policymakers were caught off-guard by the boldness and speed of the Chinese push for AIIB. Beijing’s experience trying to put together the BRICS bank over the last three years partially explains this.

Although the SCO was once China’s pet project, Beijing has lost interest in the organization: the Chinese initially saw the project as a way to extend Chinese influence in Central Asia while accommodating Moscow's interests, but the Kremlin’s fears that China would push too far into Russia’s back yard using tools like the SCO Development Bank meant that economic cooperation among SCO countries never took off. Russia also frustrated Beijing by lobbying for India’s accession to SCO as a counterweight to growing Chinese influence.

In the end, China grew tired of failed attempts to create multilateral norms-based institutions, and announced the Silk Road economic initiative instead. The Silk Road infrastructure fund totals $40 billion, and the China Development Bank has announced plans to provide $1 trillion in loans as part of OBOR. All SCO members from Central Asia are now in line for this money, as is Russia. This explains why China gave up its veto over Indian accession, brokering the incorporation of its long-time ally Pakistan in exchange. The addition of the two archrivals will make an already dysfunctional organization even more dysfunctional.

Now that China has the OBOR initiative, it can quietly observe the slow erosion of the once important SCO. As Russia attempts to use the SCO as a platform from which it can present itself as an alternative to Western hegemony, it has already ceded its role as regional economic hegemon to China.

About the Author

Director, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Alexander Gabuev is director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. Gabuev’s research is focused on Russian foreign policy with particular focus on the impact of the war in Ukraine and the Sino-Russia relationship. Since joining Carnegie in 2015, Gabuev has contributed commentary and analysis to a wide range of publications, including the Financial Times, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Economist.

- With Putin in Charge, Russia’s Vassalage to China Will Only DeepenCommentary

- BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and AspirantsResearch

- +16

Stewart Patrick, Erica Hogan, Oliver Stuenkel, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- What We Know About Drone Use in the Iran WarCommentary

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot

- Beijing Doesn’t Think Like Washington—and the Iran Conflict Shows WhyCommentary

Arguing that Chinese policy is hung on alliances—with imputations of obligation—misses the point.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- A China Financial Markets PostCommentary

Description of the post.

Michael Pettis

- How Far Can Russian Arms Help Iran?Commentary

Arms supplies from Russia to Iran will not only continue, but could grow significantly if Russia gets the opportunity.

Nikita Smagin

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …