When I resigned from the U.S. Department of State after nearly twenty-five years, I met with then secretary of state Colin Powell for a final farewell. Powell put his arm around me and delivered two pieces of advice, like Polonius to Hamlet: First, don’t try to come back; instead, treasure those unique years of service. Second—somewhat surprising from a man of such insight and intelligence—don’t spend a whole lot of time looking back. I wholeheartedly accepted the first and enthusiastically rejected the second, instead spending the last decade and a half in the public conversation trying honestly to come to terms with what we got right and wrong.

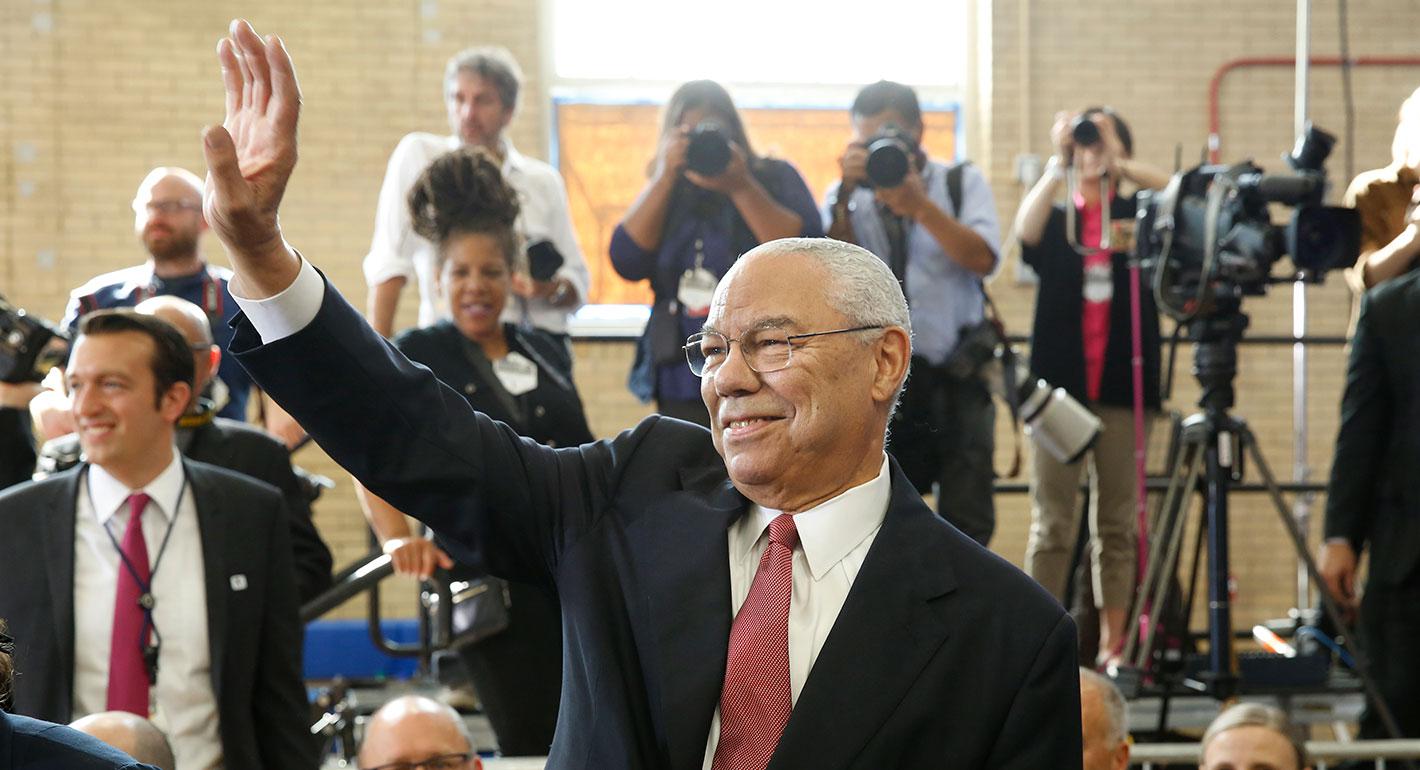

Looking back now over the two years I worked for Powell, I feel a tremendous sense of loss and sadness over his untimely passing. He was a truly unique figure in so many ways—the first African American to serve as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, national security adviser, and secretary of state and almost certainly the most popular and well-liked top diplomat in the nation’s history.

But I’ll remember him in other ways. On a personal level, Powell connected with you, and it lasted. Once entering his orbit, you felt special in his presence. I remember joking with former secretary of state James Baker that Baker had called me Andy for at least six months until he got my name straight. Whether it was his military training or his own special human resource skills, Powell got it straight from the get-go. Once you were on Powell’s radar screen, you never left.

That familiarity led to an easy interaction. While I was working on Middle East issues, Powell would frequently remind me of his knowledge of Yiddish learned from his Jewish neighbors growing up in the Bronx. Once in Jerusalem, after the White House had again undercut him, this time cutting out portions of a speech he wanted to give, he grabbed my stomach exclaiming “Aaron, they hit me right in the kishkies (intestines)!” Years later, when I saw him, he’d smile and say, “How are those kishkies?”

We didn’t make much progress on Middle East diplomacy during those years. Between leaders who were at odds, the second intifada, and a White House focused on other priorities after the attacks on September 11, 2001, there wasn’t much hope. Powell might have wanted to try something different. But he knew better, once telling me that he’d throw himself in front of a train before he’d let his young president spend two weeks at a Middle East summit as former president Bill Clinton had done. And yet, having served in Vietnam, Powell knew the cost of war and the price of one that wasn’t tethered to achievable goals. It is indeed a cruel irony that a strategic thinker like Powell—who saw the advantages of using military force successfully in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm—ended up in an administration that ignored both the lessons of the Vietnam War and the first Gulf War.

In his own way too, Powell set aside the advice he gave me and did his own fair share of looking back. He regretted, probably more than we’ll ever know, the speech he gave at the United Nations in 2003 validating the politicized intelligence that helped former president George W. Bush’s administration go to war in Iraq. Powell knew what a stain it would be on his reputation and for the interests of the nation. Some won’t forgive and will argue he should have resigned. Only two secretaries of state in the modern history of the United States have resigned on principle—William Jennings Bryan and Cyrus Vance. That just wasn’t like Powell, whose entire career was tethered to a cause and a set of institutions larger than himself.

Yes, Powell was ambitious, calculating, and focused on personal advancement. But those traits were tethered to a broader goal—the well-being, security, preservation of democracy, and pursuit of racial justice of the republic he served. Whether in uniform or out, Powell had the one characteristic all great Americans possess: the capacity to turn the “M” in “me” upside down, so it becomes the “W” in “we.”

I wish there were, and hope there might be, many more like him. We should all deeply mourn his passing.