On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

{

"authors": [

"Nancy Kwak"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Democratic Innovation"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "CC",

"programs": [

"Carnegie California"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Democracy"

]

}

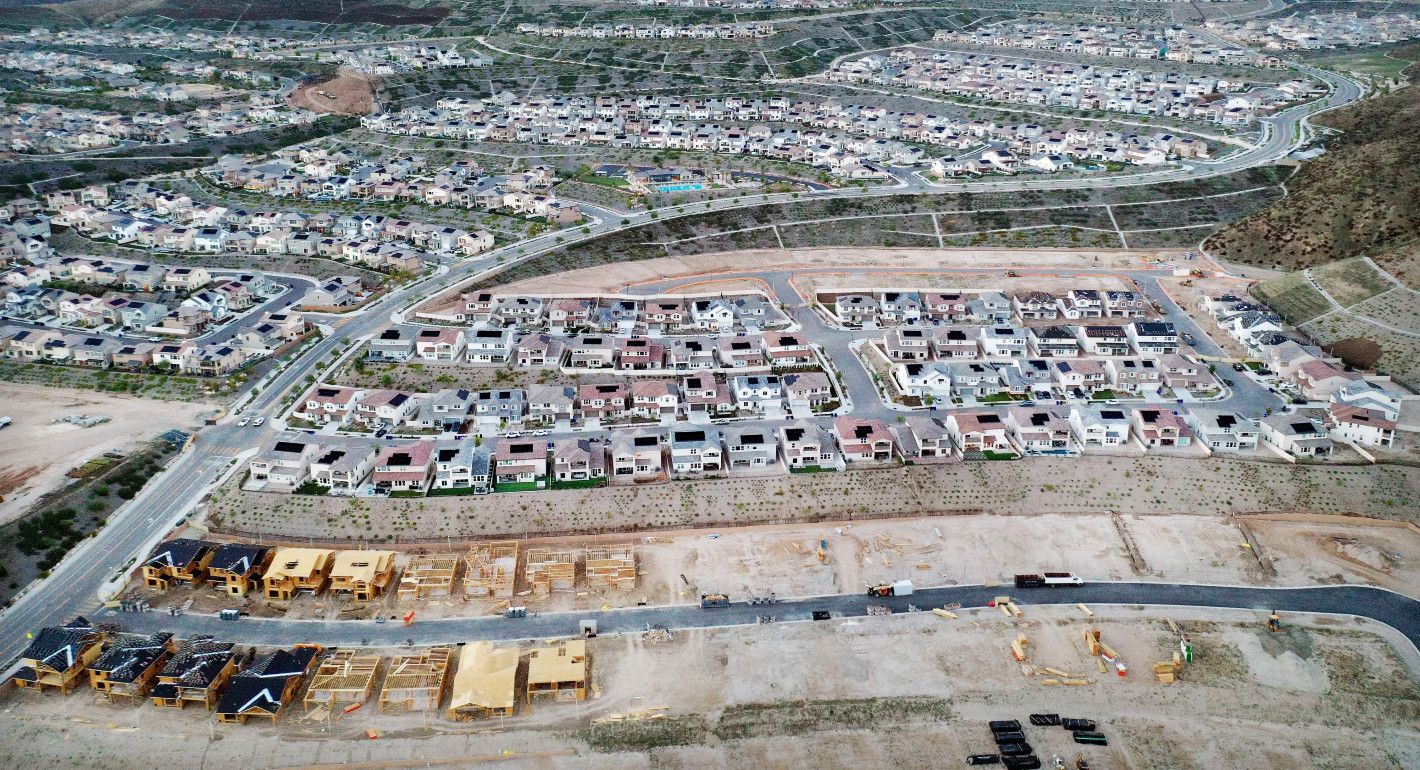

A housing development in Santa Clarita, California. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Politics and housing have myriad connections in the Golden State.

Housing is a critical issue for voters, whether at the local, state, or national level. In California, with affordability at an all-time low and homelessness rates increasing, counties such as Santa Clara, San Francisco, Orange, and San Diego are hard-pressed to find workable, affordable solutions. The crisis also has the potential to impact the ballot box in the upcoming election: according to a February study by the real estate company Redfin, over half of the 3,000 surveyed families stated housing affordability will play a role in their decisions about how they vote for president in November.

The crisis in California in particular has reached a boiling point. An April report by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office found that the price of a bottom-tier home in California is 33 percent higher than the price of a midtier home in the rest of the country. Even more extreme, a mid-tier California home is 221 percent of the price of an average home in the United States. Average hourly wages are nowhere near keeping pace: wage rates rose a paltry 18 percent while monthly mortgage payments went up by 86 percent from January 2020 to March 2024. Not surprisingly, homeownership rates have stalled for working-class families. Overcrowding has surged, while the number of people without housing continues to trend upward. According to the 2023 point-in-time count, California maintains its decade-long position as the state with the greatest number of unhoused people. Over 70 percent of the nation’s unsheltered population lived in five major cities, and those five cities were all in California.

The housing crisis is a public health, safety, and equity issue, but it also ties directly to the health of California’s democracy. Historically, political leaders have believed since at least the 1930s that homeownership rates shape political beliefs. During the Cold War, American foreign policy experts and programs nurtured mass homeownership abroad as part of a broader campaign to persuade postwar, transitional, and postcolonial regimes to align themselves with the United States and not the Soviet Union. While no national government’s political ideology or realpolitik can be attributed to a single factor, certainly in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, mass homeownership folded in with a development agenda that blended capitalism with political liberalism.

Every country’s version of this story is particular. For example, Singapore’s 1964 Home Ownership for the People Scheme promoted homeownership of “public” Housing and Development Board flats. Singaporean leaders explicitly built a homeowning society for the twin goals of building a pool of savings from which economic development might be financed, and eliminating politically active neighborhoods and fostering the literal buy-in of residents to a newly created nation by 1965. The Philippines’ 1978 Pag-IBIG Fund and National Home Mortgage Finance Corporation explicitly mimicked some of the structure of the Singaporean program by nurturing savings for national development by promoting homeownership. Mexico’s INFONAVIT, a federal institute created in 1972, has dramatically jump-started the developer-built housing industry by making affordable mortgages more widely available. Today, 70 percent of all Mexican housing loans are issued by INFONAVIT. All of this attention to homeownership at the global scale showcases the way politicians have seen increasing homeownership as a path to economic growth and political legitimacy.

Today, the connection between housing and politics can be seen in myriad ways in California. Citizens’ engagement with—and willingness to contribute to—a polity depends on their material well-being. The government must show it is actively doing something to improve life for everyday Californians or suffer the consequences of low voter turnout, ennui with the state’s referendum system, and open political rebuke. At the same time, lawmakers must address major crises like the housing shortage and affordability crisis without making existing homeowners feel their wealth is being reduced in any way. As Mark Baldassare has discussed, both red and blue Californians lean conservative when it comes to the state budget. Housing is a political requirement loaded with land mines.

Both local and state leaders understand the political significance of housing. Beginning in 2018, the state set up the Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention Program to build city shelters, permanent housing, and affordable housing. Governor Gavin Newsom put his full weight behind Proposition 1, with voters barely passing the initiative in March of this year. Starting last year, San Deigo Mayor Todd Gloria has led a California Big City Mayors group to push for more state funding, but it is struggling to justify its funding demands in the face of state budget deficits. Housing will undoubtedly show up again in bond measures this fall, pushing up against rising state debt, voter unwillingness to reallocate state funds, and general middle- and upper-class fatigue with the ongoing crisis.

Too often, Californians perceive the housing crisis to be a recent one, when the shortage has been many years in the making. During the Cold War, white homeowners mobilized a property rights movement to protect their housing values against what they perceived to be the financial costs of racial integration. Today’s housing crisis can be characterized as a lack of consensus about how much the government should do to address housing inequities broadly—a disagreement expressed more along ideological lines than along demographic or geographic ones. This so-called values-based segmentation is only exacerbated by political party alignments and specific feelings about the racial dimensions of housing inequality.

Hidden in both the property rights movement and the current concerns over social provision are the many ways that federal and local initiatives have historically opened the door to decent shelter for some and not others. In a way, the debate over homeownership connects with a larger set of beliefs about how much each household, taxpayer, or state resident ought to help right the wrongs of history. There is the longer reach of racially differentiated access to Veterans Affairs loans and Federal Housing Administration support, of redlining, and of restrictive covenants. There is the multigenerational impact of tax benefits.

Scholars and journalists have helped build a growing public awareness of the historical roots of inequality, but there is no general agreement that homeowners owe their prosperity today to historical policies. Many homeowners see the state’s housing crisis as a problem of visible poverty and blight rather than of historic inequality. This explains fluctuating voter interest in earmarking public money for affordable housing initiatives.

Structural changes have also guaranteed that affordable housing will continue to rely on the ballot box: when the California Supreme Court supported the dismantling of state-funded redevelopment agencies in 2011, affordable housing programs became even more reliant on funding through an unpredictable bond measure system and state budget. No surprise, then, that the state’s and nation’s housing crises continue to snowball into ever more daunting and complex sets of challenges. Without sustained commitments to affordable housing over profitable housing development and a broader conversation about inequitable access to housing equity, it will be difficult to turn around a crisis decades in the making. And leaving housing access to individual ballot box decisions has had decidedly undemocratic impacts on Californians’ access to decent shelter.

Former Nonresident Scholar, Carnegie California

Nancy Kwak is an associate professor in the departments of History and Urban Studies & Planning at UC San Diego. She has published books and articles on housing affordability, homeownership, gentrification, urban renewal, and transnational urban planning.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

The speech addressed Iran but said little about Ukraine, China, Gaza, or other global sources of tension.

Aaron David Miller

New thinking is needed on how global civil society can be protected. In an era of major-power rivalry, competitive geopolitics, and security primacy, civil society is in danger of getting squeezed – in some countries, almost entirely out of existence.

Richard Youngs, ed., Elene Panchulidze, ed.

Because of this, the costs and risks of an attack merit far more public scrutiny than they are receiving.

Nicole Grajewski