- +18

James M. Acton, Saskia Brechenmacher, Cecily Brewer, …

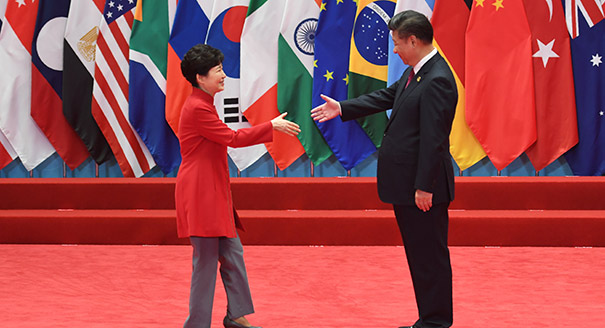

Source: Getty

China and South Korea’s Path to Consensus on THAAD

China and South Korea should delve deeper into the technical and operational aspects of THAAD to find a cooperative solution.

In July 2016, the United States and South Korea agreed to deploy the Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in the southeastern county of Seongju. Both countries believe THAAD is a necessary response to North Korea’s continued development and testing of nuclear weapons and ballistic missile technology. However, Chinese observers have repeatedly questioned the utility and security implications of introducing THAAD, claiming that it would “destabilize the security balance in the region.” Since the deployment was announced, their arguments have intensified, posing an increasing threat to China-South Korea relations. Both sides must reach a consensus on the technical aspects of the system and identify ways to address China’s security concerns.

Differences in Opinion

Despite considerable debate, including at the September 2016 G20 summit, China and South Korea continue to maintain their contrasting positions. China’s leaders assert that while the THAAD interceptors will not provide any real protection for South Korea, the system’s powerful X-band radar will effectively be able to look deep into Chinese territory. Thus, they conclude that the United States must be pressuring South Korea to deploy THAAD as part of a broader U.S. security strategy to contain China. On the other hand, South Korea’s leaders allege that THAAD will not only intercept North Korean medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles, but also the short-range ballistic missiles that pose the greatest threat.

It is true that the system would be unable to protect Seoul, even if it was deployed farther north than Seongju. However, the interception tests conducted against short-range missiles have demonstrated that THAAD can effectively protect large areas of South Korea’s central and southern regions. These missiles, with ranges exceeding 300 kilometers (about 186 miles), can reach maximum altitudes of more than 40 kilometers and, therefore, would pass through the system’s interception altitude range of 40 to 150 kilometers. Inarguably, with North Korea repeatedly threatening South Korea with total nuclear destruction, South Korea desires to first safeguard as much territory as possible and then take additional measures to shield the remaining areas. Such measures could comprise, for example, the deployment of several low-altitude missile defense systems in the country’s northern region, including Seoul.

South Korea does not consider its existing, low-altitude Patriot missile defense system capable of intercepting all of North Korea’s potential nuclear missiles. In contrast to conventional missiles, which explode upon striking the ground, nuclear warheads can be programmed to detonate at higher altitudes, which the Patriot interceptors cannot reach. Additionally, by using a lofted flight trajectory, North Korea could use medium-range and intermediate-range missiles to strike South Korean targets over shorter distances by firing them at higher angles. For example, on June 22, 2016, North Korea was able to limit the distance of the intermediate-range Musudan missile to around 400 kilometers (from a normal distance of more than 3,000 kilometers) by using this lofting method. In this scenario, the warhead is traveling at a high velocity by the end of its trajectory, thereby undermining the effectiveness of the Patriot missile system.

Given that only one nuclear warhead would be needed to inflict massive damage in South Korea, the nation feels greatly threatened by its neighbor’s nuclear posturing. South Korean leaders expect that THAAD will complement its Patriot system, giving its nation and citizens a real sense of security. Therefore, they reject the notion that THAAD’s deployment is solely the result of coercion by the United States.

The Risk to China-South Korea Relations

Counterintuitively, China’s level of investment in applying diplomatic and public opinion pressure shows that its relationship with South Korea is actually quite close. A few years ago, Japan deployed a similar defense system, but China’s reaction was far less intense. One reason for this, of course, is that Japan is located farther away from China, and therefore its systems pose less of a threat to China’s security. However, another reason could be China’s distant relationship with Japan in recent years, which may have led Chinese policymakers to conclude that they would have little influence over Japan and its deployment decision. When it comes to South Korea, however, Beijing and Seoul were experiencing a period of remarkable cooperation before the THAAD issue was raised. From China’s perspective, South Korea is more likely to address China’s concerns and adjust its plans for deployment.

However, applying forceful pressure will not necessarily lead to beneficial policy adjustments, as demonstrated by the United States’ lack of success in applying coercive measures against North Korea. Given that South Korea strongly believes THAAD is vital to its national security, the country could grow more defiant, and feelings of resentment and hostility toward China could grow. Many security experts in South Korea profess that submitting to Chinese pressure would encourage China to take even more forceful measures on similar issues.

Threats of economic sanctions are part of coercive diplomacy, but they may not be useful in addressing the THAAD issue. Adopting such punitive measures, which reportedly limit bilateral economic and cultural exchanges, would negatively impact the good relationship established between the Chinese and South Korean peoples. The relationship could be easily damaged, but difficult to repair. The newly established ties between the two nations will be essential in addressing future security concerns.

Having been subjected to severe economic sanctions during the Cold War, China has long opposed using them unilaterally. However, with its economic strength growing, China has relaxed its stance slightly, implementing small-scale, unilateral economic sanctions against several countries over the last few years. But, to what degree have these measures brought real diplomatic gains for the country? Do these gains, if any, outweigh the damage to China’s diplomatic credibility? These questions need to be thoroughly analyzed. In addition to economic sanctions, some analysts and media reporters have called for China to flex its military muscle toward South Korea.

However, neither approach will address these differences in opinion. Instead of convincing South Korea to adjust its policies in China’s favor, these forceful measures would likely be seen as a sign of disrespect and a direct threat to South Korea’s interests—which could ultimately push South Korea to bolster its military alliance with the United States.

South Korea feels that it has been treated unfairly on the THAAD issue and will not yield to strong pressure from China. But if China was to show greater empathy for its situation, and a willingness to talk and listen, it could become easier to influence South Korea’s attitude and policies.

A Path to Consensus

The two nations must engage in an honest, in-depth discussion regarding how THAAD will be used to improve South Korea’s national security and whether adjustments could be made to address the security concerns on both sides. This will be the only way to reach a consensus and identify a cooperative solution to the dispute.

The focus should not be on whether THAAD should be deployed—the deployment decision is unlikely to be reversed given the increasing North Korean threat—but rather on what middle ground can be explored to address the central issues of concern. For example, will THAAD be deployed on a temporary or permanent basis? South Korea’s own high-altitude missile defense system is still under development and currently unable to meet the threat posed by North Korea’s newest missiles; will South Korea continue to develop its system? If so, perhaps this new system could replace THAAD in a few years, making the latter’s deployment an interim solution that would be more acceptable to China. In discussing these questions, China needs to tread carefully; applying intense pressure could aggravate South Korea and cause it to fully dedicate itself to the U.S. missile defense system.

There are also other similar questions to reasonably explore. Can South Korea ensure that THAAD’s radar will be fixed in the direction of North Korea and that it will not turn to the southwest toward northern and eastern China? To what degree will the THAAD command, control, and communication functions be interlinked with the U.S. local and global missile defense network? Will data obtained from the THAAD radar be shared with Japan? Would it be possible to share the data to a certain degree with China? Although THAAD is a U.S.-supplied system, its deployment in South Korea still requires Washington to obtain Seoul’s approval of and consent to specific operational plans; therefore, if South Korea is willing to carefully consider China’s interests and concerns when deciding on these plans, it would be possible to at least reduce the potential threat to China.

Further, scholars both within China and abroad have suggested technical changes to reduce or even eliminate the negative effect THAAD would have on China’s security. For example, some scholars have recommended that South Korea replace THAAD’s X-band radar with the Green Pine radar it has already purchased from Israel. However, the benefits and feasibility of this change would have to be assessed. Use of the Green Pine radar would probably require Israel to share the underlying algorithms of the radar with the United States and maybe South Korea. The countries would also need to jointly research the compatibility between the Green Pine radar and the THAAD command and control system. In doing the feasibility assessment and research, it will be necessary for technical experts from both sides to talk directly with each other. Well-informed judgments cannot be made by policy officials or media commentators.

Moving Beyond Commitments

Following bilateral meetings at the recent G20 summit in Hangzhou, South Korean President Park Geun-hye reaffirmed her commitment to maintaining close contact with Beijing on THAAD, and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi expressed his support for holding bilateral consultations to find a mutually acceptable solution. Given their declared commitment, this is an opportune time to initiate more substantive discussions on THAAD’s central technical issues. Operational experts from both sides could jointly identify feasible alternatives and compromises, and the collaboration could foster mutual trust and understanding. A stable and friendly bilateral relationship with South Korea will be essential if China hopes to influence policymaking in Seoul—not only on THAAD but also on other security issues emerging in the Peninsula.

About the Author

Senior Fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China

Tong Zhao is a senior fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China, Carnegie’s East Asia-based research center on contemporary China. Formerly based in Beijing, he now conducts research in Washington on strategic security issues.

- Unpacking Trump’s National Security StrategyOther

- The U.S. Venezuela Operation Will Harden China’s Security CalculationCommentary

Tong Zhao

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Turkey Has Two Key Interests in the Iran ConflictCommentary

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

- Bombing Campaigns Do Not Bring About Democracy. Nor Does Regime Change Without a Plan.Commentary

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher

- How Trump’s Wars Are Boosting Russian Oil ExportsCommentary

The interventions in Iran and Venezuela are in keeping with Trump’s strategy of containing China, but also strengthen Russia’s position.

Mikhail Korostikov

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber