As the United States and China careen toward intensified economic decoupling and geopolitical rivalry, trends in the semiconductor and minerals sectors will define their strategic competition. Both great powers aim to consolidate competitive advantages by hampering the other’s technological development and hammering their trading partners. Both are doing so using increasingly damaging measures—but from opposite ends of tech supply chains. The American position remains strongest in advanced technologies, an edge that the Joe Biden administration sought to preserve and extend through an unprecedented series of export controls. China, meanwhile, is just beginning to implement a parallel export control regime that leverages its dominant market share in critical minerals as well as niche but strategic industries. The efficacy of both strategies will depend not only on each party’s execution, but also on their ability to sway middle countries toward cooperation.

Recent tit-for-tat actions mark a troubling new level of severity in this escalating struggle for technological advantage. On December 3, 2024,the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) imposed its first outright ban on the export of certain “dual-use” critical minerals to the United States. This export control went into force for germanium, gallium, superhard minerals like synthetic diamonds, and imposed additional licensing restrictions on graphite exports. In adopting this ambitious new measure, China was retaliating against U.S. semiconductor chip and manufacturing equipment export controls unveiled only the day prior. On February 4, 2025, in response to new U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods, MOFCOM announced restrictions on additional minerals including tungsten, tellurium, bismuth, indium, and products that include molybdenum. In initiating these outright bans, Beijing has aimed to mirror U.S. long-arm jurisdiction by, likewise, seeking to enforce its export controls extraterritorially in third countries, which could re-export the restricted goods to America.

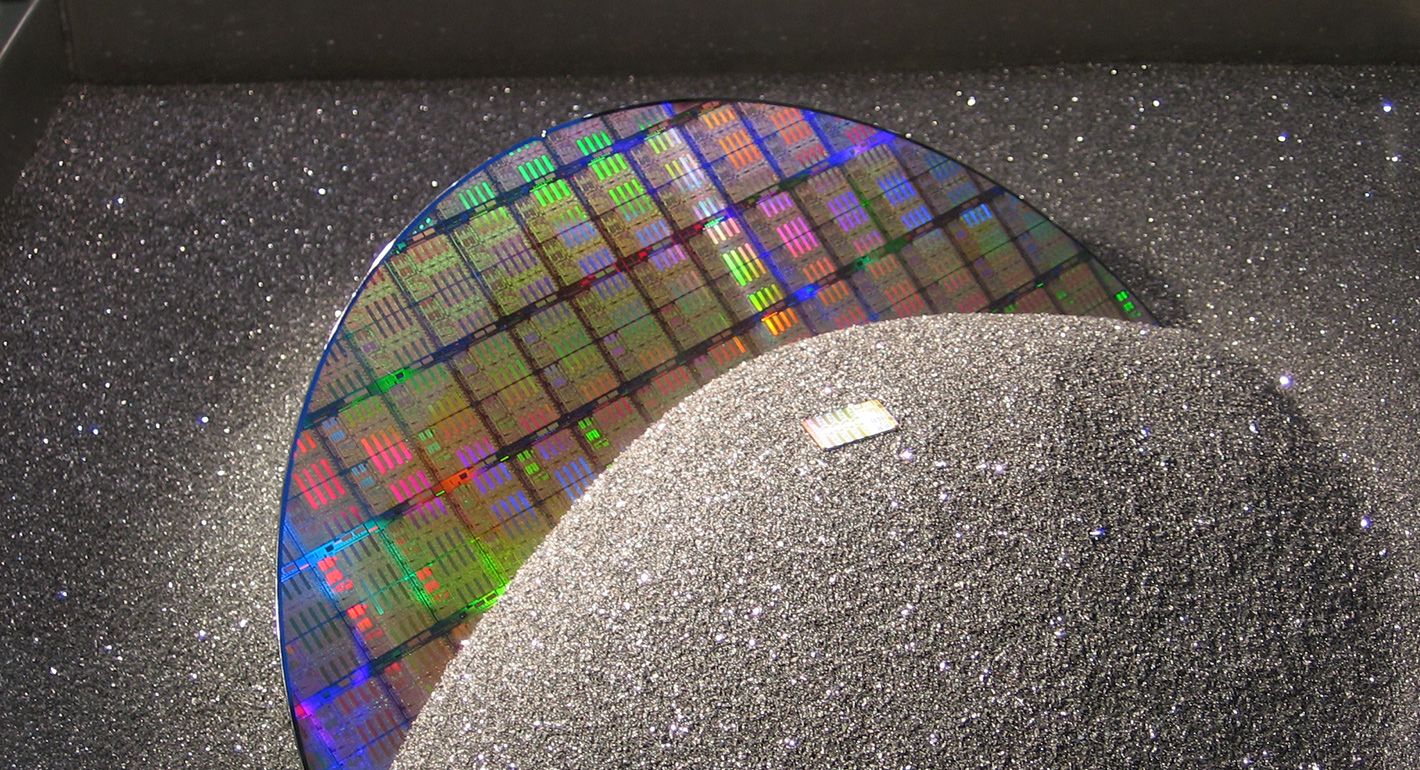

Juxtaposing “chips” and “rocks” reveals a basic asymmetry between each party’s points of strategic leverage. Beijing is building a dam upstream, threatening to choke off the flow of raw materials and intermediate goods required to produce certain advanced technologies—including semiconductor chips, high-capacity batteries, and a range of defense and aerospace products. Washington’s fortress is further downstream and depends heavily on guarding the intellectual property of American and allied firms employing the technical capabilities of a network of allies and industrial partners. This position has enabled U.S. government efforts to restrict Chinese entities’ access to the latest semiconductors and delay, but not halt, their development of cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities.

But where does the balance of leverage lie over the short- and long-term—in upstream control over critical minerals, or in downstream control over emerging technologies? Which critical minerals is Beijing most likely to restrict in the future, and what can Washington do to mitigate those impacts? What is the role of third countries in the effectiveness of targeted export controls? We address these questions first by placing this latest tit-for-tat of export controls into strategic context; second, we analyze Beijing’s objectives in developing its mineral leverage through domestic law and policy over several decades; then we assess the relative effectiveness of upstream and downstream controls, and consider the robust support that diversified trade and technology partners can provide; finally, we offer some signposts for anticipating further developments in the escalating bilateral competition for technological and military advantage.

Why China’s Mounting Mineral Restrictions are Important for Government and Industry

During the previous era of great power competition, this type of economic warfare was unthinkable. The U.S. and the Soviet Union began their Cold War contest already decoupled from one another and remained that way. Little leverage could be gained or lost through measures like mounting export controls up and down global supply chains. In the contemporary system, however, China and the U.S. remain deeply interdependent—even in spite of accelerating efforts across two U.S. administrations to reverse this reality. The grim prospect of “mutually assured disruption” now looms over both great powers as they unwind their economic ties.

China’s new export bans will not provoke the large-scale market disruptions that some fear, but they are already yielding complications for some U.S. industries, as observed in the defense sector. Regardless of immediate reactions, they are a clear signal that further weaponization of the PRC’sdominant position in strategic mineral supply chains is the direction of travel. By selecting bans on niche but strategic metals, the moves indicate that Beijing’s intent is not to disrupt global commodity markets or try to yield macroeconomic damage to the U.S.—as some have suggested—but to target acute points of pain for strategic industries. Going forward, the United States should anticipate additional PRC restrictions on critical minerals, likely including graphite, rare earths, and strategic metals related to defense and high-tech applications. Each successive salvo is likely to be more damaging and difficult to offset. Chinese actions in this space leverage its colossal market share asproducer, refiner, and supplier of most of the critical minerals required to make chips, clean energy technologies, and many defense and aerospace products.

China’s substantial control over upstream and midstream chokepoints in critical mineral supply chains is the product ofBeijing’s long-term strategy to build “self-reliance.” Chinese leaders since Deng Xiaoping have taken incremental steps to establish central control over China’s domestic mining, mineral processing, and export industries. Over decades of concerted industrial policy and regulation, China has made observable progress toward securing and indigenizing its mineral supply chains—and in the process, building extraordinary leverage over advanced economies for which these goods are critical inputs.

Meanwhile, the U.S. began employing its advantages at the other end of the international technology supply chains in earnest only in 2020. These efforts depend on America’s innovative tech ecosystem and cooperative network of advanced industrial partners to build leverage. How these distinct types of leverage will net out is uncertain and should prompt critical thinking about whether “rocks” or “chips” are the more valuable assets in long-term strategic competition.

As the supplier of key mineral inputs necessary for global production across vital industries, China wields a potent—but potentially eroding—edge in the bilateral trade and technology competition. The PRC supplies more than 50 percent of U.S. demand for twenty-four critical minerals, including more than 90 percent of demand for rare earth elements. American policymakers have shownincreasingalarm across administrations about this glaring vulnerability, but have not yet meaningfully mitigated it. Meanwhile, China has taken concerted actions to extend and secure its advantaged position, amassing economic and political leverage from its concentrations of mineral processing and export capacity.

But having finally shown its willingness to use this mineral weapon, China set in motion processes that could gradually diminish its leverage—and may even make it obsolete over time. Beijing will need to strike a cautious balance of banning materials that do not trigger a significant burden to its domestic producers and markets, nor generate the opportunity for affected parties to rapidly and collectively diversify. China’s actions could cause acute pain,already evident in the automotive sector and likely to cascade through chip and defense sectors. Mineral markets will inevitably adjust to China’s choice to act as achokepoint. By exploiting its dominant position in mineral supply chains to harm its trading partners, Beijing creates strategic pressures for other countries—particularly Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, South Korea, and the United States—to accept short-term costs in order to diversify their critical mineral trade networks. Developed and implemented in concert, these policies would dilute China’s advantages in the long term.

More extensive cooperation between government and industry will also be necessary to restore strategic balance. The outgoing Biden administration employed bothdomestic andmultilateral tools to bend the curve of mineral production away from China. However, amid elevated interest rates and a slump across multiple mineral prices, many new non-Chinese mines and refineries havestruggled to reachprojected targets. Wrangling mineral purchasers in the U.S. and elsewhere into line with Washington’s national security priorities has proven a tall order. None of the measures adopted so far has adequately diversified American critical mineral supply chains. Further rounds of painful and costly disruption are all but certain—whether imposed by Beijing’s mounting supply-side restrictions or by Washington’s lurch toward ever more extreme tariff schedules (or more likely, both). The Donald Trump administration’s aspirations for “mineral dominance” will not come without such tectonic geoeconomic movement. Over time, these developments will catalyze what looks like an inevitable shift towards parallel and competing trade and technology networks.

Background on the Dueling Export Restrictions

Washington’s “Technology Blockade”

With the slow realization that U.S. technologies were vulnerable to disruption, both the Trump and then Biden administrations oversaw accelerating efforts along two tracks. The first and most logical of them has been to make U.S. mineral supply chains more resilient, beginning with Executive Order 13817 in 2017 that recognized the United States’ “strategic vulnerability for both its economy and military to adverse foreign government action.” Both the Trump and Biden administrations continued efforts in this vein, employing measures as varied as tariffs, emergency authorities, legislation (including the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, and 2022 Defense Production Act). Both administrations also rolled out an array of subsidies, tax credits, and loans for domestic producers—albeit still falling short of activating the necessary investments and viable projects.

Alongside these efforts to shore up mineral supply chains, American policymakers have also pursued a second tack: a series of measures intended to degrade Chinese access to advanced semiconductors and the equipment and tools needed for chip production. Beginning with the short-lived ban on U.S. exports to the Chinese telecom firm ZTE in 2018, the first Trump administration continued with (evidently counterproductive) campaigns against Huawei. With a succession of amendments to the Foreign Direct Product Rule and a continually growing Department of Commerce Entity List, Trump and then Biden gradually expanded an embargo on major PRC technology firms and (some of) their subsidiaries. These actions amounted to what Chinese observers came to regard as a “technology blockade.”

In late 2022, the Biden administration further upped the stakes, passing the CHIPS and Science Act to onshore chip fabrication, and then enacting new Department of Commerce rules expressly designed to set back China’s chip industry and maintain a permanent U.S. technological advantage. Through periodicupdates—including the recent flurry of activity to tighten up what has proven to be an imperfect export control regime—U.S. policymakers have tried to build a high fence around advanced technologies.

Yet in seeking to strike a comprehensive blow to China’s tech ecosystem, America telegraphed its dire intentions without corresponding urgency in implementation. Policymakers put China on notice, but implemented export control measures in piecemeal, permitting them to be riddled with workarounds and loopholes due in no small part to relentless and effective industry lobbying. Watching this process unfold, Chinese leaders have been able to stockpile embargoed products before controls go into effect, create shell companies that circumvent the entity list, redouble efforts to indigenize its technology supply chains, and generally take urgent steps to upgrade its domestic innovative capacity. The recent release of ultra-efficient large language models from Chinese companies implies that workarounds are bearing fruit. Future American efforts should take stock of the hard lessons from this experience and apply any future measures swiftly in cooperation with allies and partners whose resource wealth, technological capacity, and markets are necessary for success.

China’s Asymmetric Export Restrictions

China’s latest salvo of export controls leverages its weight as the world’s largest trading nation and commanding position astride global production networks. Until 2023, Beijing’s primary use of economic leverage against its trading partners came in the form of undeclared restrictions on imports. China has long employed its market power as the leading commodities importer to retaliate against foreign exporters. For example, China’s huge import volumes of agriculture allowed the imposition of undeclared import bans to punish Norway (in 2010, with salmon), the Philippines (in 2012, with bananas), Canada (in 2019, with canola), and Australia (in 2021, with barley and wine). Beijing’s use of export controls was largely confined to military items, including missile systems, and chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear technologies.

However, China’s technical capacity and political impulse to restrict exports of critical minerals have been under development since at least 1986. That year, China adopted the PRC Mineral Resources Law, codifying state ownership of all mineral resources in China and signaling Beijing’s intention to more closely manage and supervise the industry. This banner legislation began a series of regulatory, administrative, and fiscal measures that have incrementally established the export control regime unveiled in 2024.

Rare earth elements (REE) have been a focal point in China’s evolving critical minerals policy. As early as 1992, China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping, declared, “the Middle East has oil; China has rare earths.” Throughout the 1990s, Chinese law and regulation gradually established a taxation, licensing, and quota system for mining, refining, exporting, and investing in REEs and other minerals considered to be “the ‘vitamins’ of strategic industries.” The upshot of these policies has been to establish a dominant upstream position in each of the seventeen REEs, in part by flooding global markets and undercutting foreign competition.

By 2009, China became an “effective monopoly producer of rare earths,” and signaled its capacity to throttle disfavored trading partners with a short-lived export ban on rare earths to Japan in 2010. This purported “ace in Beijing’s hand” was not immediately effective, however, and China was the subject of an adverse WTO ruling in 2014 that challenged its export restrictions and increased its focus on regulating domestic REE. By 2016, China’s lead industrial planning organ, the National Development and Reform Commission, unveiled a National Mineral Resource Plan for the period between 2016-2020 that created a list of “strategic minerals” (战略性款产). Among these, a sub-category of “advantageous minerals” (又是矿产) in which China controls a surplus supply includes REEs, tungsten, germanium, gallium, antimony, and graphite. This plan tasked leading research institutes to “improve its global allocation of strategic mineral resources.” Read in the context of China’s broader push for “dual circulation”—which aims to decrease PRC dependence on international markets and boost domestic consumption while increasing international dependence on China—these efforts reflect Beijing’s assessment that higher levels of autarky and enhanced coercive leverage are necessary to meet Washington’s supposed efforts at “containment.”

In line with this priority, the PRC’s State Council initiated a public consultation on an Export Control Law (ECL) drafted by MOFCOM in 2017, envisioned as a mechanism for combating the U.S. as it began to impose new tariffs and export controls on China. After several rounds of revision, the ECL was adopted as national legislation in October 2020, imposing order on a fragmented export control regime, dramatically expanding its scope, and enhancing Chinese authorities’ control and enforcement powers. In particular, the law authorizes extraterritorial enforcement (Art. 44) and “countermeasures”—that is, retaliatory actions—“where any country or region endangers the national security or interest of the People's Republic of China by abusing export control measures” (Art. 48).

The ECL’s invocation of national security in China’s export control regime tracks the overall securitization of China’s economic policy under the government of Xi Jinping. Xi’s “comprehensive national security outlook” was announced in 2014 and then swiftly extended to cover nearly every facet of Chinese governance. Each of the five chapters of the ECL refers to national security, a total of eleven mentions. The ensuing Fourteenth Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) further describes an effort to guarantee “strategic mineral resources security,” a concept that reflects Chinese leaders’ sense of vulnerability to the interdiction of raw materials required for its manufacturing sector to thrive.

These mounting “geopolitical risks for the security of China’s critical mineral supply chains” have ushered in a new set of political priorities. According to Wang Guanghua, the PRC Minister of National Resources, China faces the challenge of “a high degree of external dependence on some important mineral resources,” and therefore must “prepare for a rainy day and ensure domestic resource security under special circumstances.” That “rainy day” has evidently arrived, inspiring China to make more intensive use of its “triple advantage,” which according to researchers from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, consists of China’s resource base, production capacity, and market size. These advantages, they reason, “provide strategic space and policy tools for China to cope with geopolitical competition.”

Those policy tools began to take shape in the ensuing years. In 2022, MOFCOM published a list of technologies and products it was considering for export restrictions, including machinery to produce solar photovoltaic components, LiDAR (advanced, radar-like detection technology), and CRISPR, a biological gene editing system (much of which has not been enforced). The situation became more material as the U.S. pursued further decoupling measures and Beijing began to act, cautiously at the outset, on restrictions of minerals and adjacent products. Starting in the summer of 2023, MOFCOM mandated new licensing requirements to export gallium and germanium required for high-tech applications (like chips and circuits). By October, the list was expanded to include graphite, the largest per-mass component of lithium-ion batteries. In September 2024, similar licensing restrictions were applied to antinomy, an essential metal used across a range of military applications. These measures did not stop the flow of exports (although some importers reported difficulty in obtaining licenses); they were instead used by Chinese policymakers as mapping tools to measure outflows and impact on industry.

Perhaps the most underappreciated step in recent years was Beijing’s increasing protection of its world-leading rare earth industry, an essential phylum of minerals for national security as well as Beijing’s greatest point of mineral and industrial leverage. In December 2023, MOFCOM banned machinery required to manufacture rare earth magnets—essential components in everything from drones and F-35s to EVs. The move was, conceptually, not unlike the U.S.-backed restrictions on machines used to produce high-tech semiconductors. In the REE space, Beijing is working to preserve its “indigenous innovation,” a core tenet of China’s drive for self-reliance and even autarky in certain value chains. Given Chinese industry’s sustained dominance in rare earth refining and magnet production and the relative lack of fungibility compared to other minerals, the move was a stark signifier of where and how this dynamic could escalate.

The stage was set for the latest and most decisive salvo of Chinese export controls with the December 2024 release of new implementing regulations on the ECL. These administrative measures unified various lists of dual-use items and prohibited end-users; most importantly, they gave teeth to the extraterritorial provisions of the vague ECL, authorizing MOFCOM to take action in cases where third countries permit the transit, transshipment, and re-export of supposed dual-use items (see Arts. 48 and 49). These regulations went into effect on December 1, 2024, and served as the basis for the implementation of outright bans on gallium, germanium, antimony, and superhard metals that were enacted only two days later on December third.

The evolving export control regime summarized here is, in many respects, inspired by and modeled on American efforts. Chinese analysts have taken stock of Washington’s “consistent use of domestic law to shape geopolitical relations;” in response, Chinese leaders have gradually built up a “foreign-related law” regime that empowers its government agencies to apply PRC law extraterritorially and, perhaps more urgently, to better surveil and control its firms’ commercial interactions with foreign entities. However, it should be cautioned that the relative nascency of this institutional muscle does not guarantee its success in monitoring and restricting how firms operate abroad. America has a legacy system of extraterritorial sanctions in place, supercharged with new and bolder efforts against Russia after its invasion of Ukraine. China’s capacity to mirror such a robust network is likely quite limited in the short run, but an area to monitor closely in the coming months and years.

Potential Impact of Restrictions and Opportunities for Supply Diversification

China’s export bans on gallium, germanium, and antimony from December triggered economic ripples, but their immediate effects remain modest. Initial licensing requirements in 2023 sharply curtailed flows of these minerals and signaled MOFCOM’s capacity for further restrictions. Rather than provoke a severe disruption to U.S. industries, they preemptively triggered stockpiling. Minerals such as gallium and germanium, vital for semiconductors and high-tech circuits, have seen price spikes, but the controls have likely been circumvented by transshipment or re-export. However, the niche nature of these minerals complicates supply chain diversification. Gallium is highly concentrated in Chinese production and poses particular challenges due to its limited fungibility and critical applications in military technology. Germanium, in contrast, offers clearer pathways for alternative production in areas like Canada and the U.S., where the Pentagon is already supporting development efforts.

Restrictions on antimony, a key input for defense hardware such as night-vision goggles and ammunition, have highlighted the fragility of U.S. supply chains. Antimony prices grew 40 percent following the ban, underscoring the urgency for domestic and allied production. The U.S. is home to only one smelter, and efforts to onshore extraction remain slow, as evidenced by the $1.8 billion in government financing sought for an Idaho project. The longer-term impact could incentivize diversification to allied geographies such as Canada and Australia, though immediate gaps in supply could strain defense production, especially given the lengthy and challenging pathways to scale commercial mining.

The most recent restrictions from February fourth have yielded similar results, but with notable concern regarding tungsten. Similar to antimony in both application and geographical concentration of production, tungsten is required across aerospace and defense applications—and 80 percent of it is produced in China (this jumps to nearly 90 percent when including production from Russia and North Korea). Further, tungsten is an ultra-niche mineral with small production volumes, implying that alternative sourcing is notably limited. Upon the news of the export restrictions, Chinese tungsten producers rallied in the equity markets while Western manufacturers were in “disbelief” as they scrambled to diversify supplies. While there are a myriad of tungsten deposits across the United States, no mines are currently ready to scale alternative supplies. Other metals banned on February fourth like tellurium, bismuth, and indium also share about an 80 percent production concentration in China as well as a range of strategic and high-tech applications.

Looking ahead, China’s potential restrictions on graphite and present restrictions on superhard materials carry broader implications for U.S. manufacturing and advanced technology. Graphite, essential for lithium-ion batteries, represents a critical vulnerability for the United States, which is in the midst of a $70 billion domestic manufacturing boom in the battery sector. While diversification efforts are underway, including projects in Mozambique and Quebec, the United States remains ill-equipped to address a sudden supply shutoff. Similarly, bans on superhard materials, integral to high-tech manufacturing and defense, could disrupt access to capital equipment stock, complicating efforts to onshore advanced industrial capabilities. Whether Western allies like Japan or emerging partners like India can fill these gaps remains uncertain, underscoring the strategic pressure created by Beijing’s targeted restrictions.

For China, U.S. export controls on advanced semiconductors and chip-making equipment have created a chokepoint for China’s technological ambitions—but with notable examples of innovative workarounds beginning to materialize. These restrictions, reinforced by alliances with Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea, have sought to block access to key tools like extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines, which are required to produce high-performance graphic processing units (GPUs), leaving Chinese firms struggling to compete at advanced nodes. With over 90 percent of China’s advanced chips coming from Taiwan, Beijing faces a supply chain vulnerability, especially amid U.S. efforts to reduce the supply of advanced Taiwanese chips into mainland China.

In response, China has intensified efforts to bolster its domestic semiconductor industry. State-led initiatives and subsidies have enabled firms to achieve progress in memory chip production, while tech giants are developing efficient AI chips that rely on mature node semiconductors. Additionally, Chinese AI developers are adapting by focusing on less resource-intensive models, which mitigate reliance on cutting-edge chips. These strategies, combined with continued imports of lower-grade semiconductors, sustain technological progress in areas like consumer electronics and AI development.

Despite these adaptive measures, China’s reliance on foreign technology and materials remains a continual challenge. Structural inefficiencies, talent shortages, and limited access to critical inputs hinder its path to immediate self-sufficiency. Whether and how Beijing can overcome these obstacles will determine the resilience of its semiconductor industry and its ability to compete in an increasingly restrictive global landscape. In the interim, China will continue to double down on advancing indigenous AI and chip innovation. In the wake of recent U.S. restrictions, state-backed investors began an $8.2 billion investment fund to help backstop domestic companies.

Implications for Competition and Questions of Industrial Power

The critical question emerging amid these tensions concerns who holds the greatest levels of leverage and industrial power: the entity producing the inputs for sensitive, security-related products or the entity withholding the intellectual property to produce cutting-edge AI? Assessing this competitive balance requires gauging the potential for the respective American and Chinese institutions to rigorously enforce their desired restrictions. For example, supposedly banned AI chips, tools, and equipment have found their way into the Chinese market, contrary to Washington’s stated policy objectives. Similar outflows of banned minerals could leak into the U.S. from third countries and commodity traders despite efforts from Chinese officials to create a monitoring and surveillance system. Enforcing compliance is a daunting task on either side, especially for the Chinese given the existing U.S. instinct to rely on its sanctions regime.

A second metric for consideration is time. Thus far, both sides have largely operated with clarity about their direction of travel and have done so on timelines that allow domestic industries to adjust accordingly. In fact, the most recent PRC ban in December marks a noticeable shift in previous cadence where, for the first time, one party responded to the other’s action with an immediate, day-after reaction. Granted, these measures covered items already outlined as targets, but the swift action nonetheless indicates a shift in timescales. If this dynamic becomes more erratic and escalatory, more severe measures could unlock points of varying and unexpected hardship. Beijing is currently testing and experimenting with the limited tools it has developed thus far, with considerable uncertainty about the nature and scale of miscalculation that could emerge in a tit-for-tat battle.

Under these conditions, the U.S. will need to accelerate domestic and allied mining efforts while tightening enforcement on chip exports through global cooperation. This will be a challenging task given mounting international resistance to the Trump administration’s potential trade policies. Meanwhile, China seeks to rapidly indigenize its advanced chip industry while exploiting gaps in U.S.-led enforcement to maintain chip imports. The willingness of trade partners to comply with U.S. restrictions will be a decisive factor for both sides in achieving their objectives. But it is unclear if either country has the capacity to genuinely enforce these measures. Even if the U.S. is able to contain the flow of chips into China, Chinese firms could continue to procure greater quantities of lower-end semiconductors and take on higher costs to yield similar compute results. All the while, Beijing is killing time until higher-end production can be indigenized. Similarly, it is likely that China’s export ban on minerals could, at best, trigger inflationary spikes for U.S. industries and will not yet yield mass market disruptions. Circumvention and re-routing are more likely to result in market inefficiencies than they are to produce true industrial chaos.

Ultimately, the extent to which these efforts succeed may be the result of how well middle countries choose to follow what Washington or Beijing dictate. The recent export ban could be viewed as a signal to U.S.-allied semiconductor producers like Japan or the Netherlands that MOFCOM is willing to weaponize its mineral exports to them, as well—especially if they are circumventing flows into the U.S. market. While extraterritorial enforcement of this ban is likely beyond MOFCOM’s practical capabilities at present, foreign surveillance and shaming of non-compliant entities are imminent. Similarly, on the U.S. side, the extent to which mineral-producing allies can step up to fill the gaps created by banned Chinese minerals will be an important long-term variable. Of particular interest are the commodity producers within Five Eyes, Canada and Australia, which are well endowed with a myriad of resources and legacy extractive sectors.

Signposts and Potential Avenues Going Forward

An extension of the current export ban to other minerals could pose a blow to U.S. industries and national security interests. If the Trump administration escalates another tariff war with China while imposing even more severe containment measures across the chip supply chain, countermeasures would be guaranteed. Beijing’s recent actions signal that it would be inclined to further weaponize bans. Graphite would be a logical next step given China’s global dominance in the supply chain and that it has already stated this as a high-risk commodity. Doing so could trigger price spikes across the automobile and industrial sectors. Other potential metals could include titanium, a notable point of Chinese dominance with essential applications for the U.S. military industrial base.

Since December’s ban, MOFCOM has issued an industry commentary discussing whether it should prevent the export of a specialized and cost-effective battery technology that is gaining increasing market share and cannot yet be produced by Korean or Japanese competitors. While restricting technology transfers of this intellectual property (IP) could impact the aspirations of American and European automakers, it has limited, if any, security risk. But what it does illustrate is that China is keen to protect the IP of sectors where competition is futile and lowering restrictions would perversely benefit foreign actors who can produce alternatives.

The sum of this fear is rare earth magnets. Some have asserted that rare earths and their related supply chain could be where Beijing moves next—and doing so could cause prolonged industrial and security challenges. Rare earth elements are an ultra-niche group of specialized metals generally used to produce specialized magnetic motors in everything from EVs and consumer electronics to essential military technologies. Certain individual rare earths also are fundamental to advanced medical equipment, lasers, night vision goggles, and—most notably—AI chips. While the Pentagon has been proactive in diversifying rare earth magnet production, the supply chain is immensely complex and Chinese corporations retain a stronghold as well. Despite some scattered facilities between Estonia, Brazil, and Texas, there is no rare earth magnet supply chain outside of China capable of filling the immediate gap driven by a unilateral ban.

Going forward, the U.S. will need to act quickly to advance domestic and allied mineral production through quicker permitting and better access to financing. While the Trump administration will be inclined to promote production at home, they will confront limited domestic reserves, local opposition, and state-level permitting requirements that will show the value of bilateral and multilateral mineral policy. In the long-term, the administration should also prioritizenew technologies that depend less on the specific minerals subject to China’s stranglehold. Until these strategies bear fruit, however, American efforts to restrict China’s access to leading-edge technologies will face asymmetric retaliation from Beijing. Throttling U.S. access to critical minerals could bring pain to domestic industry and U.S. trade and technology partners. How long it lasts will depend on international cooperation to diversify and “de-risk”—urgent priorities for U.S. industrial and foreign policy that should be augmented in the years ahead.