Leaning into a multispeed Europe that includes the UK is the way Europeans don’t get relegated to suffering what they must, while the mighty United States and China do what they want.

Rym Momtaz

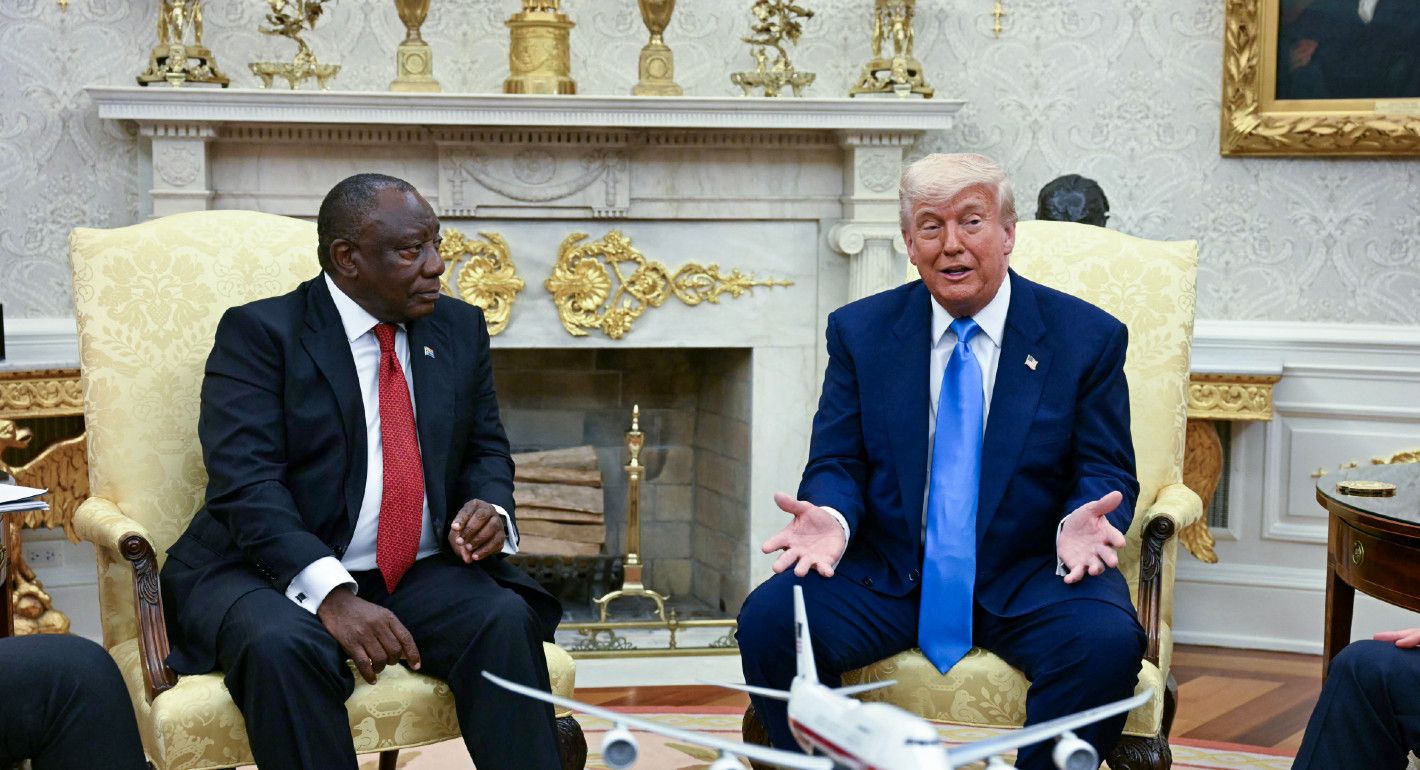

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa listens as U.S. President Donald Trump accuses South Africa of perpetrating a "genocide" against White citizens.

Despite promising not to lecture other countries on “how to live,” the Trump administration is intervening with increasing frequency and force in the political affairs of other countries.

Immediately upon taking power, President Donald Trump and his team set about pulling the United States away from its longtime stance as a supporter of democracy globally. They dismantled U.S. pro-democracy assistance programs, dissolved most of the State Department’s institutional capacity on democracy issues, and disabled most of U.S. global broadcasting, a traditional linchpin of democracy support. Trump put a ribbon on this course change in Riyadh in May when he criticized his predecessors as “interventionists” and declared that the United States would no longer give other countries “lectures on how to live.” Secretary of State Marco Rubio underlined this new policy stance in a cable to U.S. embassies around the world in July, stating that the State Department would sharply restrict commentary on foreign elections.

Yet despite this rhetorical embrace of non-interventionism, the Trump administration has repeatedly involved itself in the domestic affairs of other countries. In some cases, this involves pressuring other countries to change policies in the economic domain, such as on investment into or from the United States, on technology regulation, or on climate change, where the administration is exerting leverage to discourage other countries from moving away from reliance on fossil fuels. But in a growing set of cases, the new U.S. interventionism is directly political, aiming to influence core political-legal processes, like elections; to affect the political fortunes of other countries’ leaders or their main political opponents; or to shape outcomes on major political issues, like disputes over basic political rights.

Despite this rhetorical embrace of non-interventionism, the Trump administration has repeatedly involved itself in the domestic affairs of other countries.

The most common thrust of the administration’s political interventionism is support for politicians or political parties that Trump and his team favor—right-wing, illiberal, or anti-democratic populists, often with ties to the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC). Some of these political actors are in power, like those in Argentina, El Salvador, Hungary, and Israel; some are not, like those in Brazil, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The administration often justifies these actions in terms of protecting democracy, even though the target countries are democracies and many of those the administration goes to bat for are widely viewed internationally as threats to democracy.

In most of these cases, the administration has inserted itself rhetorically, praising the aligned politicians or their parties and criticizing their opponents. But in some instances, the Trump team has gotten far more involved, openly backing favored politicians in elections or even deploying punitive tariffs or sanctions against political or legal authorities who anger them.

This new interventionism is still in its early days—the scope and variety of actions are increasing week by week. But enough of it has occurred to warrant at least a preliminary stocktaking. This article examines some recent examples of the Trump administration’s transnational political interventionism, noting the different modalities used and the politicians or issues supported. Thus far, the administration does not appear to have achieved much through these actions, at least in terms of bolstering the popularity or standing of its favored friends or getting other governments to reverse policies it does not like. But Trump and his team show no signs of reconsidering their new interventionist line in the face of that reality and more of this new U.S. political interventionism almost certainly lies ahead.

Figure 1 presents an overview of ten cases of Trump administration interference in the domestic politics of other countries carried out in the name of defending democracy—not necessarily an exhaustive set but one that covers much of the current ground. Six of these cases are European, reflecting a strong interest on the part of Trump and his team in supporting the European far right and the relatively greater presence of the populist right in Europe compared to other regions. In these ten cases, the political actors receiving backing from the administration are all in opposition, except in Israel. Most countries where Trump-favored leaders are in power, such as Argentina, El Salvador, and Hungary, have not faced legal actions or other sorts of challenges that might trigger Trump administration interventions. One of the cases, that of South Africa, is somewhat different from the others in terms of the issue on which Washington chose to advocate—recent legislation in South Africa relating to land ownership—but it merits inclusion here because of the prominence and multifaceted nature of the Trump administration’s intrusion into the country’s political life.

The absence of criticism by the Trump administration of blatant violations of democratic norms in other countries—such as Türkiye, where opposition leader and Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu was arrested in March 2025, or El Salvador, where the Trump administration has for months actively bolstered President Nayib Bukele, received him in the White House, and rejected international criticism of his removal of presidential term limits—stands in sharp contrast to the administration’s activism on behalf of illiberal right-wing politicians and parties. Three exceptions are Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, authoritarian regimes of which the Trump administration has been highly critical, in line with previous U.S. administrations.

As these cases highlight, several issues have triggered Trump administration interventionism, all of which align with the MAGA right’s broader effort to support partisan allies abroad. At the top of the list are prosecutions of former or current right-wing leaders for abuses of power. In addition to the Bolsonaro and Netanyahu cases, the Trump administration has also thrown its weight behind Colombia’s right-wing former president Álvaro Uribe, who faces up to twelve years in prison on a corruption ruling that Rubio described as a “weaponization of Colombia’s judicial branch by radical judges.” Other right-wing leaders have clearly noticed Trump’s disdain for courts pursuing executive accountability: After a Bosnian appeals court upheld former Republika Srpska president Milorad Dodik’s political ban in August, Dodik immediately vowed to “write a letter to the U.S. administration.”

Culture war battles are a second apparent trigger for American intervention. From South Africa’s land law to France’s response to antisemitism, policy decisions contested along familiar identitarian lines abroad increasingly draw censure from Washington as well. Particularly salient among these culture war trigger points are restrictions on right-wing actors’ political speech. Vance’s aggressive positioning on the AfD firewall and Scotland’s proposed anti–abortion protest regulations suggests that other countries’ domestic politics are indeed a new frontier in the Trump administration’s larger assault on speech norms perceived as left-wing or “woke.” Asked about the Bolsonaro trial, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt commented that “this is a priority for the administration and the president is unafraid to use the economic might, the military might, of the United States to protect free speech around the world.”

A third apparent trigger is the possibility of helping an ideologically aligned party or candidate abroad in a close election get over the line: Trump officials were especially brazen in exerting partisan pressure in the close electoral contests this year in Poland and Romania.

In most cases, the administration’s actions have been high-profile, high-visibility statements of support or criticism related to particular politicians or legal actions. Only in a few cases have they gone further—most notably in Brazil, where the administration has imposed high tariffs, targeted sanctions, and visa cancellations as tools of political influence. It remains too early to assess whether the Trump team will follow the Brazilian pattern in other cases, but the administration’s actions in this case certainly stand as a warning to others. It is not clear why the administration has taken such an aggressive approach to Brazil, but one likely factor is the stark similarity between Trump and Bolsonaro as political disrupters, as embodied in the two men’s refusal to accept electoral defeat and the echo between the January 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol and the January 8, 2023, attacks on Brazilian government institutions.

The administration’s political interventions have angered the leaders of several of the countries affected. Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has rejected U.S. pressure and described it as an attack on his country’s sovereignty. After Vance’s Munich speech, Germany’s then chancellor Olaf Scholz sharply criticized U.S. support for a party that has downplayed Nazi crimes. France’s Prime Minister François Bayrou rejected comments about Le Pen by the Trump administration as “interference.” Ramaphosa took a different approach, calmly pushing back against the accusations Trump made during his Oval Office visit, and then joking about Trump’s tactics a week later in South Africa.

The political, media, and expert classes of the countries in question have also responded with anger. In the UK, Vance’s critical remarks about British policies sparked considerable derision and concern. Even the far-right chair of the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee chided Trump’s interference in Israeli legal proceedings. In Romania, the government's response to the new U.S. visa policy was more subdued, though the Foreign Ministry made clear that the policy complied with all the technical requirements, describing Trump's decision as “political.”

In some electoral settings, the Trump administration’s interventions have caused a rally-round-the-flag effect and may have increased support for parties and politicians opposed to the right-wing agenda championed by the U.S. president. Trump’s fury against Brazil seems to have increased public support for Lula and divided the right. In Romania, the mainstream candidate surged to an unexpectedly large victory in the May presidential election. It is not certain that the Trump administration’s support for the right-wing populist candidate swung many voters against him, but it seems clear that it did not significantly help him.

In some electoral settings, the Trump administration’s interventions have caused a rally-round-the-flag effect and may have increased support for parties and politicians opposed to the right-wing agenda championed by the U.S. president.

In other cases, it is at least possible that Washington’s intervention may have tipped the scales toward its preferred outcome. Given the closeness of the May-June Polish presidential election and the importance of the United States to many Poles, the administration’s intervention in favor of the conservative candidate may have contributed to his narrow victory.

Looking beyond electoral or pre-electoral effects to possible policy effects on the issues that triggered the Trump administration to intervene, it is hard to see much in the way of results. Germany has not dismantled the political “firewall” that Vance criticized. The UK has not changed its laws or regulations relating to protests around abortion clinics. The South African government has not altered its land law that so enraged the Trump administration. Neither the Brazilian government nor the judiciary has backed away from their actions and statements relating to Bolsonaro. Israeli prosecutors have not cancelled the trial of Netanyahu.

Beyond these immediate political outcomes, there is reason to believe that the U.S. interventions under Trump described above may have exacerbated numerous countries’ declining public perceptions of the United States. Polls show that the percentage of Brazilians who hold an unfavorable view of the United States has risen sharply. In Europe, too, the number of those with negative views of the United States has grown, though this is not limited to countries that have seen a U.S. intervention in their domestic politics.

In short, the direct political utility of the Trump administration’s interference in other countries’ domestic politics has thus far ranged from neutral to negative. The administration has empowered and made more popular those it has criticized and not produced any policy reversal in line with its demands. It is possible that Trump and his team view the value of their political interventionism more in symbolic terms: standing up publicly for their foreign political allies. Or they may believe these actions will constrain future measures or developments in other countries that they might not like—in effect using these cases to put governments on notice all around the world of the United States’ newfound willingness to bully fellow democracies on issues important to the Trumpian political worldview. It is also possible that Trump and his team have not stopped to calculate the cost-benefit tradeoff of their foreign interventionism and are just proceeding from case to case, fueled by ideological conviction and the news of the day.

This means that it is difficult to predict the specific course of this new interventionism in the affairs of other democracies. Certain political contests where Trump favorites or their successors are likely to be competing may well attract such attention, like next year’s parliamentary elections in Hungary and presidential elections in Brazil. In other cases, the administration’s focus may be legal developments affecting an out-of-office right-wing political figure or a new culture war issue that gains online prominence. The low practical utility of the administration’s interventions may become more apparent to Trump and his team over time, leading them to start to trim their interventionist sails. Or the early spate of such actions may become a regular stream over the next several years, as assertive cross-border ideological reflexes harden into a well-developed muscle and are applied to a widening range of democracies and issues.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Leaning into a multispeed Europe that includes the UK is the way Europeans don’t get relegated to suffering what they must, while the mighty United States and China do what they want.

Rym Momtaz

As Gaza peace negotiations take center stage, Washington should use the tools that have proven the most effective over the past decades of Middle East mediation.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes, Kathryn Selfe

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

A prophetic Romanian novel about a town at the mouth of the Danube carries a warning: Europe decays when it stops looking outward. In a world of increasing insularity, the EU should heed its warning.

Thomas de Waal

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown