In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

{

"authors": [

"Maged Mandour"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Sada",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Israel",

"North Africa",

"Egypt",

"Levant"

],

"topics": [

"Security"

]

}

Source: Getty

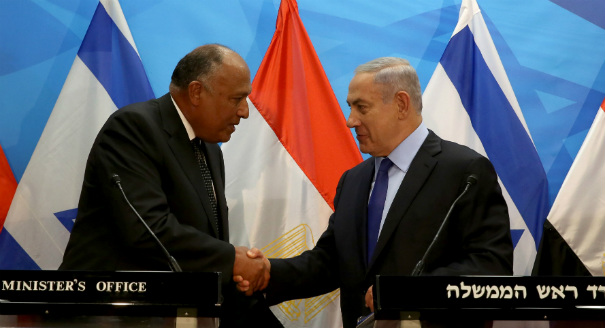

Growing cooperation between Egypt and Israel will have direct implications on Cairo’s ability to play its traditional role as a mediator in the Palestinian peace process.

On February 19, the private Egyptian firm Dolphinus Holdings announced a deal to import $15 billion worth of natural gas from Israel over a period of ten years. This firm is one of the first to take advantage of a new natural gas law passed in August 2017 that ended the state’s monopoly on storing and trading natural gas using the national grid, part of a series of reforms aimed at addressing Egypt’s persistent natural gas shortage. Although rumors spread that the imported gas might be possibly re-exported to Europe in order to accumulate foreign currency reserves instead, the agreement to import from Israel is also indicative of nascent economic ties between the two neighbors. Egypt’s changing relationship with Israel will have direct implications on Cairo’s ability to play its traditional role as a mediator in the Palestinian peace process.

This not the first a gas deal between Egypt and Israel. A deal to export Egyptian gas to Israel—signed in 2005, when Egypt was producing more natural gas and domestic demand was lower—collapsed in 2012 amid Egypt’s energy crisis and after several attacks by insurgents on the export pipeline in Sinai. In May 2017, a Swiss arbitration court ordered Egypt to pay $3 billion in fines to Israel for halting these exports. The General Intelligence Services (GIS) played a direct role in establishing the companies used to export to Israel under the 2005 gas deal, prompting popular speculation that Dolphinus Holdings, which signed the new gas deal, is also connected the security services—especially given the large scale economic expansion of the military over the past few years. Similarly, an Israeli trade delegation visited Cairo in April 2016 for the first time in ten years to discuss a possible expansion to the Qualifying Industrial Zone (QIZ) agreement originally signed in December 2004. Although no updates were made to the QIZ agreement, this visit was another sign of potential economic ties.

In recent years, Egypt’s security cooperation with Israel has also grown. Israel has reportedly conducted more than 100 airstrikes in Sinai since July 2015 in support of Egyptian efforts to counter the growing insurgency in the peninsula. The Egyptian military denies that they had approved these strikes. However, in January 2017 a top Israeli defense official confirmed there was close cooperation with Egypt in Sinai, including Israel’s quick approval for the Egyptian military’s requests to build up its forces there—for which Israeli approval is required under the Camp David accords and which Israel had in the past viewed with caution. In addition, in April 2014, in part due to Israeli pressure, the United States released the delivery of ten Apache helicopters that had been withheld when military aid to Egypt was suspended following the 2013 coup, citing the need to maintain both Egyptian and Israeli security.

Egypt’s position on the Trump administration’s decision to move the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem also reflects growing political ties. Even though Egypt drafted the UN Security Council resolution condemning the move, which was vetoed by the United States, a member of the GIS is heard on leaked tapes instructing a number of TV show hosts to build public support for the transfer and convince their viewers that the Palestinians should accept Ramallah as their future capital. Furthermore, Egypt has been pushing for the peace process to resume. In a speech at the UN in September 2017, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi called on both Israelis and Palestinians to take advantage of a “historic” opportunity to make peace. This reiterated his May 2016 declaration of support for the French push to revive the peace process, during which he indicated his willingness to do whatever is necessary to ensure the success of the talks, promising “warmer” relations with Israel if the Palestinian issue were resolved—a stance that was publicly welcomed by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. According to a report published by Haaretz, Sisi, Netanyahu, and Isaac Herzog (the head of the Zionist Union and leader of the opposition in the Knesset) held a secret meeting in Cairo in February 2016 to discuss the push for peace talks, including the possibility of creating a coalition Israeli government that would be able to make peace.

The increased security cooperation between the two countries—and the gas deal’s potential to expand their economic ties—compromises Egypt’s traditional role as a mediator. This is compounded by broader regional realignments, particularly Saudi Arabia’s shift toward viewing Israel as a possible ally in its struggle against Iran. Saudi Arabia and Israel have increased their military cooperation to fight terrorism, as stated by outgoing CIA director Mike Pompeo in December 2017. Saudi Arabia has also shown an interest in purchasing Israeli weaponry, namely tanks and missile defense systems. This shift has partially uncoupled Saudi–Egyptian–Israeli relations from the Palestinian issue, allowing Arab states to pursue closer relations with Israel. However, the continued occupation of the Palestinian territories and the Egyptian and Saudi fear of a public backlash obstruct closer cooperation between the three countries, including possible normalization of relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel. The desire for such cooperation thus makes settling the Palestinian issue more pressing.

These regional conditions mean the Palestinian issue is less likely to be settled in a manner that satisfies the Palestinians’ minimum demands. For example, based on a leaked Saudi plan for a two-state solution that Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman presented to Mahmoud Abbas during a meeting in Riyadh in November 2017, the Palestinians would give up East Jerusalem as the capital of their future state, refugees and their descendants would not be allowed to return, the Israeli settlements in the West Bank would remain, and the future Palestinian state would have a non-contiguous territory with limited sovereignty. These conditions are almost impossible for any Palestinian leadership to accept.

Egyptian foreign policy is now primarily dictated by the regime’s concerns for survival. As such, the main goal of Egyptian foreign policy has become to secure allies who can help suppress possible domestic disturbances or prop up the regime. Both Saudi Arabia, through financial aid and investment, and Israel, through security cooperation and lobbying in Washington, have helped Sisi strengthen his position. Yet the shift in Egyptian foreign policy goals has effectively ended its ability to act as a mediator in any potential peace process, thereby worsening the already dire position of the Palestinians.

Maged Mandour is a political analyst and writes the “Chronicles of the Arab Revolt” column for Open Democracy. Follow him on Twitter @MagedMandour.

Maged Mandour

Maged Mandour is a political analyst who is a regular contributor to the Arab Digest, Middle East Eye, and Open Democracy and author of an upcoming book entitled “Egypt Under Sisi.”

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

Iraq’s foreign policy is being shaped by its own internal battles—fractured elites, competing militias, and a state struggling to speak with one voice. The article asks: How do these divisions affect Iraq’s ability to balance between the U.S. and Iran? Can Baghdad use its “good neighbor” approach to reduce regional tensions? And what will it take for Iraq to turn regional investments into real stability at home? It explores potential solutions, including strengthening state institutions, curbing rogue militias, improving governance, and using regional partnerships to address core economic and security weaknesses so Iraq can finally build a unified and sustainable foreign policy.

Mike Fleet

How can Saudi Arabia turn its booming e-commerce sector into a real engine of economic empowerment for women amid persistent gaps in capital access, digital training, and workplace inclusion? This piece explores the policy fixes, from data-center integration to gender-responsive regulation, that could unlock women’s full potential in the kingdom’s digital economy.

Hannan Hussain

Hate speech has spread across Sudan and become a key factor in worsening the war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces. The article provides expert analysis and historical background to show how hateful rhetoric has fueled violence, justified atrocities, and weakened national unity, while also suggesting ways to counter it through justice, education, and promoting a culture of peace.

Samar Sulaiman