Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

{

"authors": [

"Tamer Badawi"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Sada",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Iraq",

"Middle East"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Political Reform",

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

Despite Baghdad’s expansionary spending, citizens in the country’s oil-rich south continue to protest. Government reforms need to recognize the interconnectedness of the country’s economic, climatic, and security conundrums.

Since the summer of 2015, oil-rich southern Iraq has been seeing demonstrations protesting poor services. In early June 2024, protesters in Samawah, the capital of the southern province of Muthanna bordering Saudi Arabia, mobilized against corruption.

Protests in Samawah began in 2011 over poor services. Provincial protests continued in 2015 and 2018. In the latter, protests developed into a 20-day sit-in after anti-corruption protests commenced and faced a violent crackdown in neighbouring Basra.[1] In parallel to the Tishreen demonstrations in Baghdad, Samawah’s protesters held local protests from 2019 to 2021.

A key figure in recent protests is Hamid al-Yasiri, the commander of the 44th brigade of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), a government-sanctioned coalition of brigades consisting of Shia armed groups. Al-Yasiri led protests against the newly elected local government following the December 2023 provincial elections and called on Baghdad to appoint a “military governor” to govern the province instead. Before joining the PMF to combat the ‘Islamic State’ group (ISIS), al-Yasiri was the representative of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani—Iraq’s most senior Shia cleric—in Muthanna, making him an influential figure.

The protests swiftly led to a meeting between a provincial delegation he led and Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani. The PM publicly expressed eagerness to address the delegation’s grievances. Al-Yasiri vowed to continue protests unless the six demands are met. Al-Yasiri’s demands essentially seek to unseat the provincial governor and transfer control of provincial affairs to the protest movement’s leaders.

The most politically-sensitive demand is the closure of all “economic bureaus” in the province. For example, political parties with armed wings reportedly imposed royalties across provinces, seeking to benefit from the post-conflict reconstruction spending spree. The Iraqi government officially banned these bureaus in 2019.

A political activist in Samawah’s protests explained that when public funds were allocated from the central government to Muthanna, following the passage of the 2024 budget, al-Yasiri learned of a joint corrupt scheme between the local government and bureaus linked to political parties.[2] Muthanna’s financial allocations in the 2024 budget remain the lowest among the provinces, with a 2.8 percent share, a small increase from 2.4 percent the previous year.

The International Monetary Fund in its 2024 Article IV Consultation report assesses in its that economic growth will increase in 2024, driven by an expansionary three-year budget. Yet, the high spending is mismatched with an anticipated decline in oil price, leading to risks to the country’s economic stability.

Apart from corruption, Hamid al-Yasiri’s mobilization of protesters in June is also indirectly linked to a schism among some of the four PMF brigades associated with the holy shrines in Najaf and Karbala—of which al-Yasiri is part—and some of the PMF brigades run by Iran-allied ‘resistance’ armed groups and the governing Coordination Framework.

Following years of simmering tensions among the four brigades and the pro-resistance segment of the PMF brigades over PMF leadership, the shrine-linked PMF brigades were operationally separated in April 2020 from the PMF Commission and linked directly to the Iraqi General Commander. However, the Shrine-linked brigades in the PMF remain financially connected to the resistance-dominated PMF Commission.

Nevertheless, the separation of the Atabat brigades did not defuse tensions between the two camps. In August 2021, without naming them directly, al-Yasiri accused Iran-allied resistance armed groups, which have significant influence in the PMF, of being “loyalists to foreign powers” and accused them of “treason.” In January 2022, unknown assailants fired on Al-Yasiri’s house.

The endurance of intra-PMF cleavages and corruption triggered Samawah’s recent protests, but the drivers are structural and characteristic of several provinces in Iraq: poverty, poor services, climate change, water scarcity, internal displacement, weak rule of law, and tribal violence.

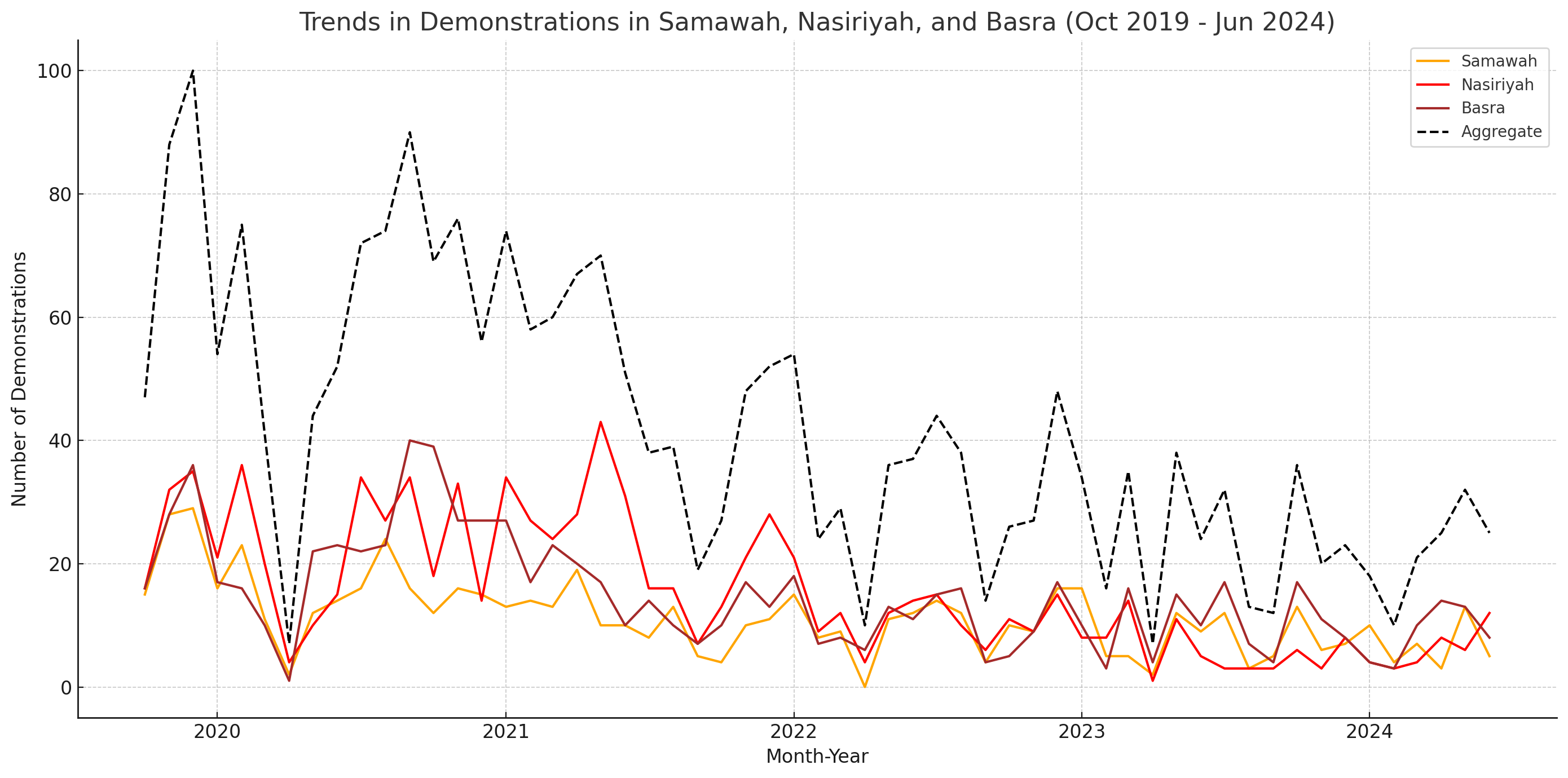

While demonstrations in southern Iraq have significantly decreased compared to 2019 levels, they are roughly similar to 2023 (see figure 1). The success of Samawah protests in pressuring the central government to consider its demands has temporarily stabilized the situation and prevented cross-provincial escalation.

In conclusion, unrest in Muthanna is a stark reminder of Iraq’s unresolved challenges and the cyclical nature of protests. The temporary calm that followed recent protests is unlikely to last long unless the government takes bold and comprehensive actions to tackle corruption, climate change induced problems, and remedy security sector divisions. PM Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani needs to offer clear pathways for reform and change that recognize the interconnectedness of the country’s conundrums.

[1] An interview with a political activist from Muthanna conducted through a messaging app. June 2024.

[2].The previous interview.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

Iraq’s foreign policy is being shaped by its own internal battles—fractured elites, competing militias, and a state struggling to speak with one voice. The article asks: How do these divisions affect Iraq’s ability to balance between the U.S. and Iran? Can Baghdad use its “good neighbor” approach to reduce regional tensions? And what will it take for Iraq to turn regional investments into real stability at home? It explores potential solutions, including strengthening state institutions, curbing rogue militias, improving governance, and using regional partnerships to address core economic and security weaknesses so Iraq can finally build a unified and sustainable foreign policy.

Mike Fleet

How can Saudi Arabia turn its booming e-commerce sector into a real engine of economic empowerment for women amid persistent gaps in capital access, digital training, and workplace inclusion? This piece explores the policy fixes, from data-center integration to gender-responsive regulation, that could unlock women’s full potential in the kingdom’s digital economy.

Hannan Hussain

Hate speech has spread across Sudan and become a key factor in worsening the war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces. The article provides expert analysis and historical background to show how hateful rhetoric has fueled violence, justified atrocities, and weakened national unity, while also suggesting ways to counter it through justice, education, and promoting a culture of peace.

Samar Sulaiman

The August 2025 government decision to restrict weapons to the Lebanese state, starting with Palestinian arms in the camps, marked a major test of Lebanon’s ability to turn a long-standing slogan into practical policy. Yet the experiment quickly exposed political hesitation, social gaps, and factional divisions, raising the question of whether it can become a model for addressing more sensitive files such as Hezbollah’s weapons.

Souhayb Jawhar