Dmitri Trenin

{

"authors": [

"Dmitri Trenin"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [

"China’s Foreign Relations"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"East Asia",

"China",

"Russia",

"Eastern Europe",

"Western Europe"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Foreign Policy",

"Security"

]

}

Source: Getty

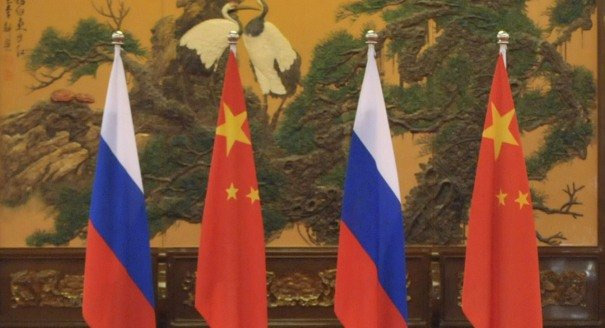

China’s Victory in Ukraine

China will study U.S. strategy toward Russia and draw its own conclusions. Its interests are in keeping Russia as its stable strategic hinterland and a natural-resource base.

Source: Project Syndicate

For a generation, relations between the United States and Russia were essentially about history. Since the Cold War’s end, Russia had become increasingly peripheral to the US and much of the rest of the world, its international importance and power seemingly consigned to the past. That era has now ended.

To be sure, the current conflict between the US and Russia over Ukraine is a mismatch, given the disparity in power between the two sides. Russia is not, and cannot even pretend to be, a contender for world domination. Unlike the Soviet Union, it is not driven by some universal ideology, does not lead a bloc of states ruled by the same ideology, and has few formal allies (all of which are small). Yet the US-Russia conflict matters to the rest of the world.

It obviously matters most to Ukraine, part of which has become a battlefield. The future of Europe’s largest country – its shape, political order, and foreign relations – depends very much on how the US-Russian struggle plays out.It may well be that Ukraine becomes internally united, genuinely democratic, and firmly tied to European and Atlantic institutions; that it is generously helped by these institutions and prospers as a result; and that it evolves into an example for Russians across the border to follow. It may also be that at the end of the day, several Ukraines emerge, heading in different directions.

Ukraine’s fate, in turn, matters to other countries in Eastern Europe, particularly Moldova and Georgia. Both, like Ukraine, have signed association agreements with the European Union; and both will have to walk a fine line to avoid becoming battleground states between Russia and the West. Similarly, Russia’s nominal partners in its Eurasian Union project – Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan – will need to balance carefully between Russia, their nominal “strategic” ally, and the US, which holds the keys to the international political and economic system.

What happens to Ukraine matters to Western and Central Europe, too. Even though an enduring military standoff along NATO’s eastern border with Russia would pale in comparison to the Cold War confrontation with the Warsaw Pact, Europe’s military security can no longer be taken for granted.

And as security worries on the continent rise, EU-Russia trade will fall. As a result of US pressure, the EU will eventually buy less gas and oil from Russia, and the Russians will buy fewer manufactured goods from their neighbors. Distrust between Russia and Europe will become pervasive. The idea of a common space from Lisbon to Vladivostok will be buried. Instead, the EU and the US will be aligned even more closely, both within a reinvigorated NATO and by means of the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.

Japan has a stake as well: its decision to join the US-led sanctions against Russia means foregoing plans to build a solid relationship with the Kremlin to balance China in Asia. The US-Japan alliance will be reaffirmed, as will Japan’s position in that alliance. In a somewhat similar way, South Korea will need to bow before US demands to limit its trade with Russia, potentially eliciting a less cooperative Kremlin stance on the divided Korean Peninsula.

As a result, the US-Russia conflict will probably lead to a strengthening of America’s position vis-à-vis its European and Asian allies, and a much less friendly environment for Russia anywhere in Eurasia. Even Russia’s nominal allies will have to look over their shoulder to the US, and its forays into Latin America and enclaves of influence in the Middle East will be of little importance.

There is only one exception to this pattern of heightened US influence: China. The sharp reduction of Russia’s economic ties with the advanced countries leaves China as the only major economy outside of the US-led sanctions regime. This increases China’s significance to Russia, promising to enable the Chinese to gain wider access to Russian energy, other natural resources, and military technology.

China will study US strategy toward Russia and draw its own conclusions. But China has no interest in Russia succumbing to US pressure, breaking apart, or becoming a global power. Its interests are in keeping Russia as its stable strategic hinterland and a natural-resource base.

Chinese support for Russia to stand up to the US would be a novelty in world affairs. Many do not view it as a realistic scenario; Russia, after all, would find an alliance with China too heavy to bear, and, whatever their ideology or whoever their leaders, Russians remain European.

That may be true. Yet it is also true that one of the most revered Russian heroes from medieval history, Prince St. Alexander Nevsky, successfully fought Western invaders while remaining loyal to the Mongol khans.

There is no question that Russia will pay a price for its actions in Ukraine. The question for the US and its allies is whether exacting that price will come with a price of its own.

About the Author

Former Director, Carnegie Moscow Center

Trenin was director of the Carnegie Moscow Center from 2008 to early 2022.

- Mapping Russia’s New Approach to the Post-Soviet SpaceCommentary

- What a Week of Talks Between Russia and the West RevealedCommentary

Dmitri Trenin

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Duqm at the Crossroads: Oman’s Strategic Port and Its Role in Vision 2040Commentary

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Governing Aging Economies: South Korea and the Politics of Care, Safety, and WorkPaper

South Korea’s rapid demographic transition previews governance challenges many advanced and middle-income economies will face. This paper argues that aging is not only a care issue but a structural governance challenge—reshaping welfare, productivity, and fiscal sustainability, and reorganizing responsibilities across the state, private sector, and society.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares