Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Baunov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Russia",

"Western Europe"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Democracy",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

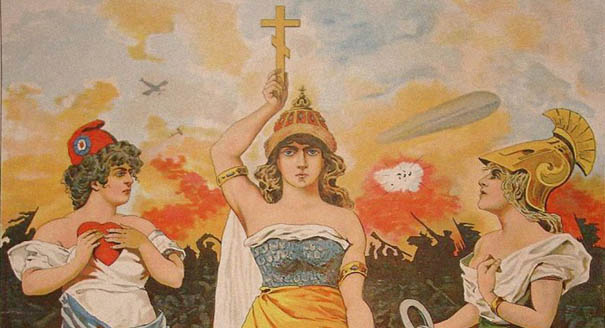

Source: Getty

Why the St. Petersburg Summit of the Kremlin’s Friends Failed

Putin and his policy attract sympathizers in Europe from both far left and far right. However, Russian ideologists have such a poor idea of who supports them overseas that they failed to assemble and present a convincing contingent of supporters, only embarrassing themselves in the end.

The Russian leadership likes to say that it only has problems with European politicians, not European nations. There is perfect mutual understanding on that front, since all people basically think in the same fashion—they like their own and familiar things and dislike everything foreign and new, which makes them similar to the Russian people, in the way they are presented by the Kremlin in the last few years.

The St. Petersburg summit of conservative sympathizers with Russia has morphed into a gathering of fringe elements that are considered fascists even among the West’s extreme right. It turned out that Russian ideologists have a poor idea of what kind of support they attract overseas. They failed to assemble and present a convincing contingent of supporters, only embarrassing themselves in the end.

For Russia, But Against Each Other

Indeed, President Putin has quite a sizable fan club in Europe that extends beyond the fringes. Just read the comments relating to any article on Russia in any European newspaper. And despite our pledged commitment to traditional values, which Europeans have compromised, the members of the club are roughly evenly split between the right and the left. In her many interviews, the head of the French National Front, Marine Le Pen, talks about restoring a sense of pride to a great nation, while the Marxist-leaning Greek Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, calls for lifting the anti-Russian sanctions and tackling the problem of rising fascism in Ukraine.Since our traditional values are also comprised of both right- and left-wing legacies, and we are now against revolutions but for the Soviet Union, we can find common ground with both camps. Our ideologists would probably want to organize a parade of all our supporters, but we can’t get all of them together: our left-wing Greek friend Syriza is fighting tooth and nail with the Golden Dawn Party, our right-wing Greek friend. In fact, the Golden Dawn parliament members are now on trial for the murder of a left-wing activist. So, the extreme right and the extreme left won’t sit at the same table.

We would have a hard time sitting alongside the European left as well. True, they oppose the United States and its Ukrainian puppets—eight Spaniards were just arrested back home for fighting under the red banner for the Donetsk People’s Republic. They came all the way to Donbas to give the coal mines back to the miners, which conjures up the images of the Soviet Union assisting the Spanish Republicans during the Spanish civil war in the 1930s. But the same groups from the European left support same-sex marriage and modern art that has been known to offend our sensibilities.

Therefore, the unreliable left was put on the backburner in favor of the right, but the right let us down too. It is hard to call this gathering the right-wing international, though. It wasn’t cobbled together on the basis of its members’ right-wing views; the only criterion for joining was the support for Russia’s recent initiatives–—from its struggle for the one and only proper sexual orientation to the independence of Donbas. Were it not for this criterion, the forum could have attracted the Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, and Ukrainian extreme right, but they were nowhere to be found.

It wasn’t quite clear what is to come out of this gathering; therefore, it was decided that the Rodina (Motherland) party, which is not even represented in the parliament, would sponsor it. Rodina would then take the fall in case things don’t work out. Of course, not every political party that has no representation in the parliament would have sufficient funds to host a conference in the Holiday Inn; nor would any political party be allowed to organize an international forum. St. Petersburg authorities disrupted a modest lecture by a political analyst, Stanislav Belkovsky, around the same time. It is also hard to imagine that this is a completely independent initiative in light of the fact that the Rodina party called itself “the president’s special force” during the 2013 regional elections, and its head, Alexei Zhuravlev, who was elected leader of the revamped Rodina, remained a member of the United Russia faction in the Duma.

A Recipe for Failure

The outcome was quite depressing, though. No matter how much they wanted to organize a parade of the European pro-Russian conservative forces, they have failed to do so. They got the participants together, but the forum failed miserably.

One of the reasons behind the failure is that many among the European right can’t stand Putin, and many of these people also can’t stand one another. For instance, Farage of the United Kingdom Independence Party doesn’t like Le Pen, and she answers in kind. It is understandable that the nationalist international doesn’t work that well in general, since its goal is separation, not unity. What unites the nationalists, however, is the awareness of their historic mission. These are not the people who want to win the election, fulfill their election promises, and quietly hand the power over to their successors. The stakes are higher here. They believe Europe is on the wrong track, and they have to set it straight. This messianic zeal brings them closer to Putin and raises their self-esteem quite high. But it doesn’t elevate their status in the diplomatic protocol.

The right-wing international could get together anywhere in Europe, but they had to be invited by someone of a higher rank than the stooges from the Rodina party. Respectable arch-conservatives could have responded to Putin’s personal invitation or an invitation sent by someone from his close circle. After all, some of them see themselves as his associates in helping to bring about the conservative tide in Europe.

However, it’s beneath Putin as a head of a great power to call the leaders of opposition movements. He can do that once they win. But when the host of the party invites his guests over, he shouldn’t send his friends and associates invitations through his porter. Only those who don’t care would answer the porter’s call—or in this case, the call of a party that is not even represented in the federal parliament. Take Roberto Fiore, for instance. The Italian politician, who openly praises fascism, was patiently listening to how the speakers at the St. Petersburg forum curse Ukraine’s fascist junta, just after returning from Kiev, where he went to build bridges with his Ukrainian counterpart, Svoboda.

The European far right also has tiers. Some of its adherents have long been participating in elections; they are represented in parliaments and occasionally join coalition governments. If the organizers had played their cards right, a more decent sampling of the European right could have come to St. Petersburg: Marine Le Pen’s National Front, the Flemish Block, the Austrian Freedom party, and maybe even the Swedish democrats or the Norwegians from the Progress party.

The low-level invitation was not the only reason why the representatives of these movements didn’t visit St. Petersburg. They were increasingly less likely to appear in Russia’s second capital as more and more fringe groups put their names on the guest list. The German National Democratic Party, the Greek Golden Dawn, the Italian New Force, the British National Party, or Nathan Smith of the Texas independence movement are not the groups or individuals that the more mainstream conservative organizations want to associate themselves with. The same goes for the Russian participants: Marine Le Pen would visit the Russian leaders, but not the leaders of the Russian Imperial Movement. The guest list and their appearance scared the obedient Russian politicians so much that even the Rodina head himself didn’t show up at the conference.

While the organizers have real supporters and sympathizers in Europe, they failed to present them in St. Petersburg. Apparently, it is not enough to have a vague idea that one has allies; one should also know who they are and how to invite them properly. However, the state created the atmosphere in which not only opposite political views, but also the mere knowledge of how the outside world really works, presents a problem and obstructs one’s political career; it therefore should come as no surprise that those entrusted with rallying Russia’s friends will inevitably attract friends of the same ilk.

This publication originally appeared in Russian.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Baunov is a senior fellow and editor-in-chief at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

- Could Russia Agree to the Latest Ukraine Peace Plan?Commentary

Alexander Baunov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- What Does War in the Middle East Mean for Russia–Iran Ties?Commentary

If the regime in Tehran survives, it could be obliged to hand Moscow significant political influence in exchange for supplies of weapons and humanitarian aid.

Nikita Smagin

- Bombing Campaigns Do Not Bring About Democracy. Nor Does Regime Change Without a Plan.Commentary

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher

- Global Instability Makes Europe More Attractive, Not LessCommentary

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

- How Trump’s Wars Are Boosting Russian Oil ExportsCommentary

The interventions in Iran and Venezuela are in keeping with Trump’s strategy of containing China, but also strengthen Russia’s position.

Mikhail Korostikov

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont