Amr Adly, Hamza Meddeb

{

"authors": [

"Amr Adly"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Egypt",

"North Africa"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Political Reform"

]

}

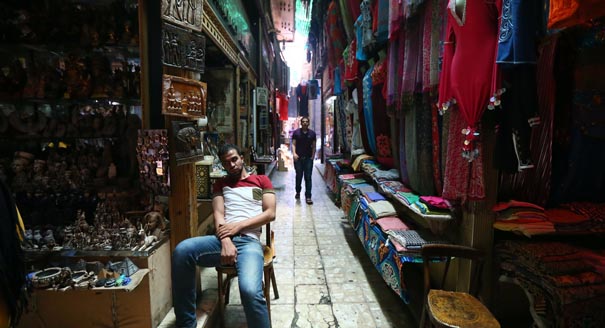

Source: Getty

Analysis: Egypt economy 'entered a vicious circle'

The Egyptian economy continues to stagnate due to a lack of long-term planning and domestic instability.

Source: Al-Jazeera

The Egyptian economy has suffered from a general slowdown since the revolution of January 2011.

Political uncertainty, macroeconomic instability and global economic turmoil since the 2008 crisis have all contributed to Egypt's prolonged recession, soaring unemployment and foreign currency shortages.

Low growth rates led to a sheer drop in state revenue and to an explosion in the budget deficit and public debt.Foreign currency generating sectors such as tourism and foreign direct investment in the energy and property sectors were hard hit by political and security uncertainty, leading to the consistent dwindling of foreign reserves, which dropped from around $35bn in January 2011, to less than $15bn in December 2012.

Ever since, the Egyptian government has been dependent on massive capital inflows in the form of aid and cheap credit from the Gulf countries to fill the ever-widening financial gap.

This has failed to introduce a structural remedy to the country's balance of payment deficit, however, given the general economic slump.

Following the election of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in June 2014, there were hopes that the economy would start showing signs of recovery. The government counted on securing massive foreign investment inflows as its main strategy.

Large inflows would reconcile the seemingly contradictory goals adopted by the government of reducing the budget deficit while relaunching the economy.

The Sharm el-Sheikh conference was held in March 2015, in the hope of translating the international support for Egypt's new regime into investment flows, especially from Gulf region allies and sponsors, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

However, things have not gone as planned. Despite the relative stabilisation in Egypt after four years of turmoil, the regional and global economy entered a new phase of contraction with detrimental effects on Egypt's chances of economic recovery.

The collapse in international oil prices had a negative impact on Egypt's energy exports, which still count for 40 percent of total exports.

Moreover, it has negatively impacted on the capacity of the economy to attract foreign direct investment into the energy sector, which has accounted more than two-thirds of such investment since the 1990s.

The deepening crisis in the eurozone took its toll on non-oil exports, as the European Union remains Egypt's largest export market. Moreover, the slowdown in the Chinese economy has led to a stagnation of the Suez Canal revenue, despite the large investments put into the new canal, which opened in August.

The Russian plane crash in the Sinai dealt a strong blow to the already embattled tourism sector in a way that would add more pressure to already thinning foreign currency earnings.

The Yemen adventure, together with halved oil prices, has also had a negative effect on the capacity of Egypt's allies to maintain their generous aid schemes, which amounted to about $23bn in the past two years.

Foreign currency shortage can be held as the Achilles heal of the Egyptian economy. The central bank's option for defending foreign reserves and the national currency through reducing imports has negatively affected the industrial sector's ability to access necessary production inputs.

Around two-thirds of Egypt's imports are made up of raw material and intermediate and capital goods. Restraints on capital mobility and anticipated devaluations of the pound have also deterred foreign investors from pouring money into the Egyptian economy.

In conclusion, the economy has entered a vicious circle where it is feared that the current dollar shortage would impede economic recovery and thus usher the economy into deeper recession in the coming few months.

The parliamentary elections, held last November, are expected to formally conclude the second transitional period that started with the military takeover of July 2013.

The upcoming parliament is expected to ratify more than 300 pieces of legislation which were issued by the executive since mid-2013. It is unlikely that the centre of power would shift away from the presidency.

However, the parliament might contribute positively to the consolidation of a political regime in Egypt through the provision of institutionalised channels of mediation between state and society.

This, however, is not likely to happen fully given the low turnout and what appears to be widespread public apathy. Moreover, it is not clear how the parliament, as fragmented as it already looks, will operate in the absence of any clear majority block.

Egypt has relatively stabilised in the short term. Unlike the period between 2011 and 2013, no major changes in the structure of political authority are expected in the coming few years.

However, longer-term sources of uncertainty persist. The future of political Islam, and the remnants of the Brotherhood, remains unanswered.

The upcoming parliament does not seem to enjoy wide popular support. Moreover, the combination between economic recession and rising inflation may prove to have negative socio-political repercussions in the medium term, especially on the middle classes and the urban poor.

It is not yet clear whether this will have repercussions on the overall sustainability and stability of the political regime, given the recent crackdown on almost all of the significant opposition groups.

In the immediate term, the Egyptian government does not have many options but to cope with the economic pressures generated by the global economic crisis and regional turmoil.

The Egyptian government needs a more predictable and transparent foreign exchange policy that could combine the seemingly contradictory goals of defending the national currency, rationing imports while at the same time re-launching growth, exports and attracting foreign investors.

Whereas the government may impose foreign currency restraints on some sectors so as to limit the pressure over dwindling reserves, it should nevertheless provide exceptions for sectors that generate dollar earnings such as exports, tourism and FDI-related activities.

This should provide a way out of the spiral of low reserves leading to lower growth and, hence, to lower foreign currency earnings.

In the medium term, Egypt needs to address its more structural problems and go beyond mere crisis-management.

To start with, state finances require serious restructuring. The ratio of tax revenue to gross domestic product is quite low for a low to middle income country such as Egypt. There is a need to expand the tax base to include property and capital holders.

On the expenditure side, the state should expand its role in investing in education, healthcare and infrastructure instead of spending more than 90 percent of its budget on recurrent expenses such as wages, subsidies and debt service.

The restructuring of public finances will require a medium to long-term sociopolitical settlement.There must be a way for the reintegration of different political and societal groups back into the political system.

Moreover, the country is in need of a social dialogue through which the overall model of development can be rethought and redesigned to combine growth-generation and development with social justice and popular legitimacy.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Scholar, Middle East Center

Adly was a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center, where his research centers on political economy, development studies, and economic sociology of the Middle East, with a focus on Egypt.

- Why Painful Economic Reforms Are Less Risky in Tunisia Than EgyptArticle

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Other Global Crisis Stemming From the Strait of Hormuz’s BlockageCommentary

Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Duqm at the Crossroads: Oman’s Strategic Port and Its Role in Vision 2040Commentary

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani