The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

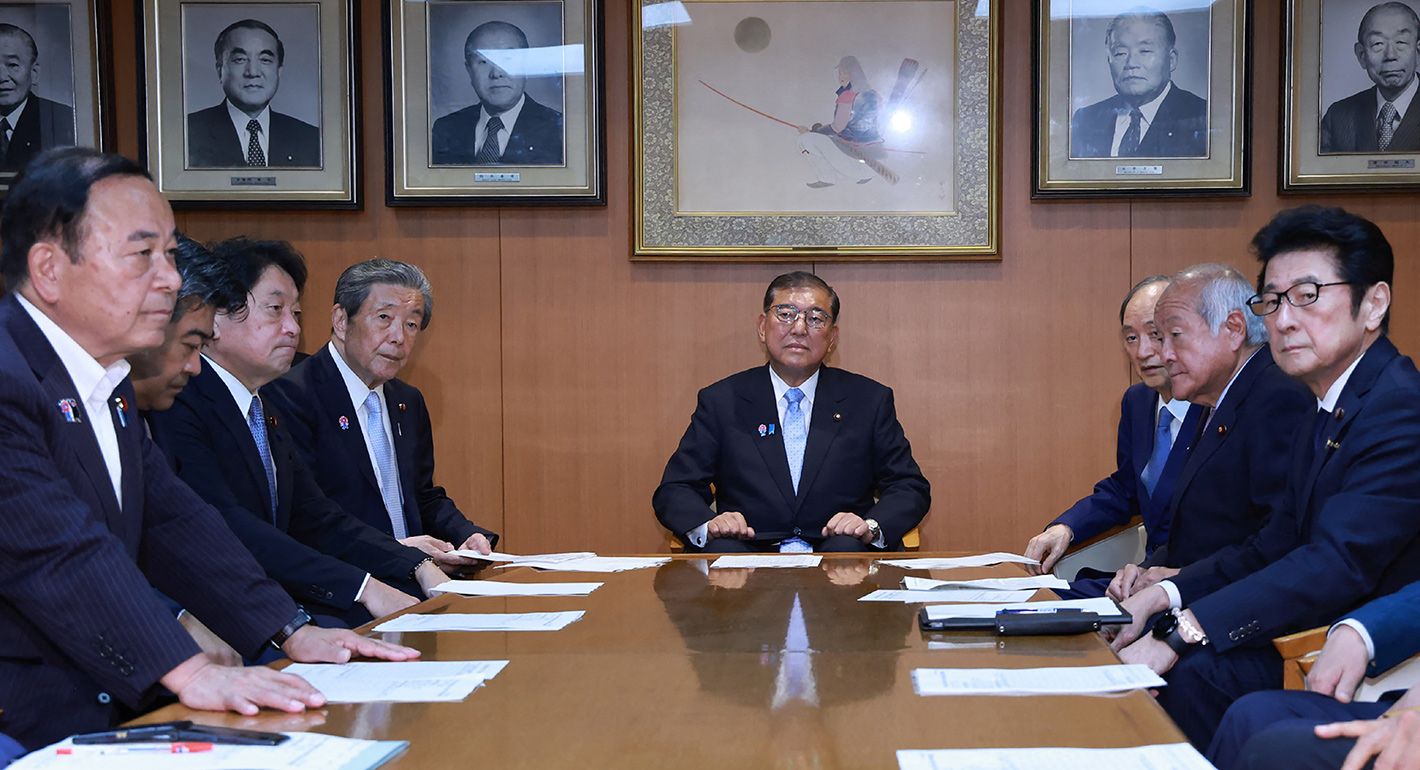

Source: Getty

With the resignation of Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru, Japan’s next leader faces a challenging international and domestic landscape. Reeling from electoral defeats, the LDP must navigate security and economic relationships with the United States and China while addressing domestic economic and social policies.

On September 7, 2025, a Sunday, Japan’s Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru announced he would resign, triggering an election within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to choose its next leader. Although the LDP does not have majorities in either the upper or lower houses, the next LDP president is likely to become the next prime minister (barring some extraordinary coalition-building among opposition parties that have so far refused to cooperate).

The election will take place on October 4. Since Japan will have a new prime minister, now is a good time to review the current state of Japanese policies and the trajectories that have led to the events about to unfold. The international challenges Japan faces are difficult, but relatively easy to understand. Ishiba and his predecessor, Kishida, had been navigating them well. The domestic challenges, however, are far more difficult—both to understand and to navigate.

Geopolitically and economically, Japan is sandwiched between major powers whose intentions are uncertain and whose next moves are unpredictable. Japan has explicitly identified China as a primary security threat, but its economy is deeply linked to China through supply chains and as a destination market. In fact, between 2020 and 2022, Japan’s export value to China was slightly greater than that to the United States. (We will see what happens with U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs in the next months and years: while exports to the United States may decline somewhat, a sizable portion of Japan’s exports to China then made their way to the United States, making the relative effects of tariffs difficult to predict.)

At the same time, Japan relies on the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance for defense. Critically, the alliance includes the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Positioning itself as America’s strongest ally in the Pacific, Japan followed U.S. sanctions on China in areas such as semiconductor-related equipment, as well as U.S. sanctions on Russia, Iran, and elsewhere. Japan is sandwiched between China as a security threat and the United States as the security provider, with its own economy deeply intertwined and reliant on both. While occasional frictions arise to varying degrees with China, which tend to be aggravated when Japan’s leadership swings right, this has been a relatively stable situation despite continued unease over Taiwan.

This overwrought situation is changing dramatically under the second Trump administration. After threatening NATO and the United States’ neighboring allies Canada and Mexico, Trump is openly criticizing the terms of the U.S.-Japan alliance as “one sided” and “unfair,” obligating the United States to defend Japan but not vice versa. He said similar things during his first term, but then prime minister Abe Shinzo managed to cultivate an unusually friendly personal relationship with Trump, seeming to succeed in keeping deeper U.S. criticism and substantive action against Japan at bay. However, in Trump’s second term, with Abe having been assassinated in 2022, and Trump’s threats toward NATO and its allies more explicit than ever before, high levels of uncertainty now surround the U.S.-Japan relationship.

A question at the forefront for many Japanese leaders, as well as the general public, is whether the United States will defend Japan in the event of a Taiwan contingency that spills over into Japanese territory. This is a major issue facing the next prime minister.

The challenging security environment facing Japan’s next prime minister was demonstrated in highly visible fashion with the enormous parade in Beijing on September 3rd commemorating the end of World War II (Victory Day or often referred to as Victory over Japan Day in China). The parade that brought Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un as front row participants was a stark reminder to Japan of its security vulnerabilities. From Japan’s perspective, the spectacle of nuclear missiles, long-range and short-range artillery, all manner of air and seafaring drones, various autonomous weapons, and a large portion of equipment seemingly aimed at showing off China’s capability of invading Taiwan, was appropriately threatening. Beyond China, Russia, and North Korea, leaders from countries including Myanmar, Iran, Pakistan, Malaysia, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Belarus, and others also participated in the parade, symbolizing Beijing’s efforts in organizing countries outside the U.S. and European alliance.

Yet, even as Beijing made a strong show of its military might, Japan was being shaken down economically by U.S. trade negotiations. So-called reciprocal tariffs on Japan were not at the punitive levels as Vietnam, China or Taiwan, but the economic pain was deep and hit just as the Japanese public was already reeling from their first real experience with inflation in decades. The United States enjoyed a strong negotiating position vis-à-vis Japan, since many major Japanese industries, including its largest, the automobile industry, are highly dependent on the United States. By threatening extremely high tariffs and making no exception or special treatment just because Japan was an ally, Japan was placed into the difficult position of hoping to promise enough in investments, purchase agreements, and market access in order to avoid economically catastrophic punitive tariff rates. All the while, the Trump administration exerted extra leverage on Japan by questioning the security relationship and strongly signaling the link between the two issues.

The trade agreement reached in July lowers most tariffs to 15 percent, including automobiles, but Japan was forced to promise approximately $550 billion in investments in the United States, to projects and target areas selected by the Trump administration. The United States would keep 90 percent of the profit beyond recouping the initial investment. If Japan refuses to make any investment, the United States can respond by increasing tariff rates. While some ambiguity remains in the language of the agreement, and the very legal basis for the Trump administration’s non-sector specific tariffs are being challenged in the courts, Japan had little leverage in the negotiations.

In the all-important relationship with the United States, Ishiba’s visit to the White House in February 2025, shortly after the Trump administration came into power, went surprisingly smoothly. Many in Japan were concerned how Ishiba would get along with Trump, since the former’s style was quite different from the personable and smiley posture that Abe took toward Trump to build a personal relationship. It was only later into Trump’s tenure that the “Zelensky moment” of open conflict occurred, and Japan was relieved that Ishiba’s relationship with Trump started on cordial terms. Managing the relationship with Trump and his administration will be a key, high stakes challenge for Japan’s new prime minister.

Ishiba, also like his predecessor Kishida, was dovish on China and South Korea. Ishiba met with Xi on the sidelines of APEC in November 2024. Neither side explicitly raised contentious issues such as disputed islands. In June the following year, relations improved further when China resumed importing Japanese seafood after a blanket two-year ban following Japan’s release of treated water from the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power plant. China also did not explicitly name Japan in the Eightieth Victory Day celebration.

With South Korea, Ishiba immediately formed a constructive and forward-looking relationship with President Lee Jae Myung when the latter visited Tokyo before meeting Trump at the White House in August. Shortly after this meeting, Ishiba made a big show of hosting Indian Prime Minister Modi, taking him on a bullet train ride and touring a semiconductor plant in an attempt to deepen economic ties.

Like his predecessor Kishida, Ishiba has been navigating a challenging external environment for Japan reasonably well given the cards he was dealt. The formula has been to stay unwaveringly loyal to the United States while maintaining as cordial relations as possible with China and simultaneously strengthening all other bilateral and regional relationships such as with India, Southeast Asian countries, the EU, NATO, and actively engaging with various frameworks such as APEC, ASEAN, the QUAD, and others.

If the next LDP leader takes hawkish stances or hardline views against China, South Korea, or any other, Japan is likely to feel far deeper pain from its current status sandwiched between major powers.

In Ishiba’s resignation announcement, he contended that his main rationale for resigning was to prevent an “irreparable division” in the party. Ishiba’s resignation announcement preempted a meeting within his party scheduled for the following day in which LDP parliamentarians would gather signatures for a motion to hold an emergency party presidential election. Only a simple majority would be needed, and many observers predicted that the motion would pass. When the party leadership announced that those who signed the motion would have their names made public, possibly as a deterrent measure, it triggered a large number of social media postings by LDP politicians publicly announcing their position to call for new leadership. This was quite a visible fissure in the LDP. These fissures predated Ishiba, but the LDP’s electoral losses since Ishiba took power exacerbated them.

The LDP is in a weak electoral position. However, its electoral defeats were not landslides, and it remains strong enough to avoid being replaced by a coalition of opposition parties or a single rising alternative party.

Under Ishiba, the LDP and its coalition partner Komeito, lost their majorities in both the lower house and upper house. But compared to when the LDP lost power in 2009 through a landslide defeat, the LDP coalition just barely lost the majority. The LDP is therefore strong enough to become preoccupied with internal political power struggles, since it is not in such dire straits that members must put aside their differences for the sake of the party’s survival. Ironically, it was this strength that led Ishiba to worry about the party splitting if the LDP called for signatures to hold a party presidential election.

A deeper dive into Japan’s electoral dynamics will follow in another piece, but it is worth taking a snapshot view of the LDP’s electoral position in the National Diet of Japan. Japan’s parliament has a lower house, which is relatively more powerful, with the prime minister holding the ability to call for an election at any point. The smaller upper house has half of its members elected every three years.

Upon becoming prime minister on October 1, 2024, Ishiba immediately called for lower house elections. In this election, the LDP lost sixty-eight seats, ending up with 191 of the 465 lower house seats (233 is needed for a majority). With its coalition partner the Komeito, the LDP coalition had 215 seats. While they were eight seats short of a majority, the opposition parties were smaller and unwilling to join in a grand coalition to dislodge the LDP coalition, leaving it in power.

While the LDP was substantially weakened, the trajectory of its defeat was quite different from the runup to the 2009 election when it lost power altogether to a single opposition party, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). The DPJ had surged in seat numbers over several election cycles to offer a real alternative to the LDP. In the 2009 landslide, the DPJ gained 195 seats to secure 308 out of the 480 lower house seats (241 needed for majority), while the LDP lost 177 seats to end up with 119. This is what a major landslide defeat of the LDP looked like. Compared to then, the 2024 LDP losses were serious but not immediately catastrophic.

In the upper house, where half of the 248 seats are up for election every three years, the recent election took place on July 20, 2025. Here too, the LDP and Komeito lost, ending up with 122 seats–just three shy of a majority. Yet, this was by no means a landslide. Its base mostly held, and the opposition parties are still fragmented to the point that they are very unlikely to create a large party that can get a majority of seats.

Under most circumstances, losses in both chambers would be enough to immediately sink a prime minister with calls from within the party to resign. However, Ishiba insisted that he needed to remain in power until trade negotiations with the United States were settled. His trade negotiator, Cabinet Minister Ryosei Akazawa, visited Washington eight times by the eve of the July 20 upper house election since Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs were imposed in April.

However, in a development that surprised most observers, Akazawa and his team reached a tariff agreement on the day after the LDP’s upper house election loss. This seemed to have sealed the fate of Ishiba in the eyes of many party members, who began mobilizing more aggressively to call for his resignation. There were still a few remaining glitches with the trade deal that needed to be ironed out, including some tariff levels that were erroneously added on top of one another, which Akazawa and his team were able to get the United States to correct in another trip. Finally, the U.S. and Japanese sides had claimed quite different obligations in the July 21 trade agreement, but there had been no written agreement. Akazawa took his tenth trip to the U.S. and produced a written agreement about the conditions for Japan’s tariffs. At this point, Ishiba no longer had U.S. tariff negotiations as a bulwark against calls for his resignation.

Japan’s new prime minister will have to deal with an enormous $550 billion dollar investment commitment, which is roughly equivalent to Japan’s annual tax intake, into areas stipulated by the Trump administration. Domestic opposition parties could easily criticize the LDP for reaching a costly deal, but Japan’s new prime minister will be in a difficult position: taking criticism for a costly deal versus the possibility of higher tariffs if Japan does not comply, which would be both economically and politically painful.

Ishiba’s approval ratings had tanked by the July upper house elections. The writing was on the wall for his replacement following a clear pattern of LDP prime ministers being replaced after disapproval ratings exceed approval ratings for an extended time. This was the case for five of the last seven LDP prime ministers preceding Ishiba, with the exceptions being former popular prime ministers Koizumi Junichiro (2001–06) and Abe Shinzo (2006–07, 2013–20). Koizumi had promised earlier that he would resign after five years, which he did. Abe resigned in his first stint as prime minister due to illness, and in his second term, he ended up becoming Japan’s longest serving prime minister.

When Ishiba’s disapproval rates far exceeded his approval ratings, with his disapproval rate peaking just before the July Upper House election at 31 percent approval and 42 percent disapproval, his time was limited.

Interestingly, his popularity actually improved after the LDP’s upper house loss, possibly because of the tariff agreements and the unexpected rise of a far right party that made Ishiba’s centrist approach more palatable to a large portion of the general public. However, this was not enough to save him from the strong moves from within his party to call for new leadership.

Much of Ishiba’s electoral malaise was a product of how he was elected. How the LDP elects its leader matters because it can potentially make the crucial difference between electing a reformer or a far right conservative. It could put Japan on a path of economic reform and good relations with its neighbors or focus Japan on more economic redistribution with strained relations with neighbors—or a combination of these positions. The LDP has two ways to call for an election: an abbreviated version that includes only LDP parliamentarians, or a “full spec” election that includes both LDP parliamentarians and general LDP party members who pay annual dues.

In 2024, when Ishiba was elected, an unprecedented nine candidates ran for the presidency. This was caused by a partial breakdown in the LDP’s internal mechanism of coordinating and compromising between internal factions. The LDP was historically organized into groups of intraparty mini-parties, who had leaders, semi-independent fundraising budgets, and internal allocations of financial resources. Factions developed because under Japan’s old system of elections until 1993, multiple candidates from the same party could run and LDP factions made sure that LDP candidates did not accidentally split the vote and end up all losing. Factions remained even after the electoral system changed, and faction leaders negotiated who would run for party president, with some factions pledging support to one candidate or another. As a result, historically, far smaller numbers of LDP presidential candidates battled one another as proxies for coalitions of factions jostling to gain power to defeat other factions.

The era of factions dominating the LDP came to an end in 2024, when a series of political funding scandals that eventually brought down the Kishida administration led to most of the factions dissolving. Any LDP member who can gather twenty signatures from LDP parliamentarians can run for the LDP presidency, and historically, power-broker faction leaders mediated and coordinated among groups of LDP members. Without the factions, an astonishingly large number of members calculated that they should declare candidacy.

The unpredictability of this LDP election dynamic led to unexpected results. A broad range of candidates from far right to center-left positions, older and younger generations, male and female, economic reformers and conservatives dispersed much of the vote. No one achieved a majority. Following party procedures, the two candidates with the most votes then competed in a runoff election. They ended up being moderate Ishiba Shigeru and far right candidate Takaichi Sanae.

The type of LDP presidential election—whether abbreviated or full spec—matters because had the LDP used an abbreviated election, the result would have been quite different. The full spec election included both LDP parliamentarians and general LDP members, but there was a major gap between how these two groups voted. Among LDP parliamentarians, the young economic reformer Koizumi Shinjiro, son of the former popular prime minister Koizumi Junichiro, was the most popular candidate. (The elder Koizumi took conservative postures on Japan’s foreign policy, but advocated deep economic reform.) Therefore, had only the LDP parliamentarians voted in an abbreviated election, the two runoff candidates would have been Takaichi and Koizumi. However, despite his popularity among LDP parliamentarians, Koizumi was far less popular among general LDP members than either Takaichi or Ishiba.

Who are the general LDP members? While the LDP does not publicly release detailed data on its members, they are generally considered to be more conservative than the general voting public. The LDP’s core organizational support comes from sectors such as agriculture, construction, small- and medium-size firms, doctors, and rural areas; the LDP does better electorally in rural areas than urban ones, and among older people rather than younger people. Becoming an LDP member entails paying a modest 4,000 yen (approximately $27) annual fee, with two years’ membership typically enabling members to vote.

The LDP general party members likely rejected Koizumi because he advocated economic reforms that included labor reforms and introducing greater competition into the economy. (His father had done the same.) Koizumi the reformer therefore probably threatened conservative, rural, and relatively domestic-oriented, globally uncompetitive sectors that depend on government regulatory and financial protection. They feared reform might be their undoing. Therefore, the moderate Ishiba, who promised rural and regional economic revitalization and a rebalancing away from urban-centered economic development, gained support, propelling him over Koizumi to be the runoff candidate.

LDP parliamentarians, however, overwhelmingly preferred Koizumi over Ishiba. Many calculated that the general public would likely prefer the young, telegenic, and energetic Koizumi promising bold economic reforms rather than Ishiba, a sixty-seven-year-old, less telegenic long-time politician promising regional economic redistribution. Simultaneously, LDP members were positioning themselves according to their relative proximity to each candidate with an eye toward their own positions within the party in the near and mid-term future.

General LDP member votes are not included in a runoff, with results determined by only LDP parliamentarians and one vote per prefectural LDP organization. Both the LDP parliamentarians and prefectures voted for Ishiba, giving him the LDP presidency, and thus, the prime ministership.

Ishiba’s win, however, was not a blowout. Takaichi is running again and will likely be a strong contender in the upcoming LDP election. Koizumi decided to run as well.

In the past, when the prime minister resigns, there have been times that the LDP chooses to run the abbreviated presidential election. The most recent was when Abe stepped down after nine years as prime minister. Abbreviated elections can happen faster, leaving less time to the LDP’s internal debates and power broker maneuvering that are widely covered in the media—often framed as “politics as usual.” Had the LDP held an abbreviated election when Kishida stepped down, Koizumi and Takaichi would likely have been in the runoff, and there would have been no way for Ishiba to become prime minister.

Had either the economic reformer Koizumi or far right Takaichi become prime minster, the LDP might have attracted younger voters, held onto some of its far right supporters, and potentially made a difference to the LDP’s fortunes in the lower and upper house elections.

This time, the LDP again decided to run a “full spec” election, including LDP members. A calculus for the LDP is that when it is losing members—as it has been recently—having greater engagement through general member voters can help party members’ morale. Too many abbreviated LDP elections may beg the question of why one should become a paying member if they have little to no voice in the party?

In this 2025 LDP election, there may again be many candidates, although with the LDP having fewer seats in the Diet, it is harder to gather the twenty Diet LDP member votes to run as a presidential candidate. However, the dynamics outlined here should be kept in mind when plotting the likely trajectories of Japanese politics based on various polls, surveys, and machinations among LDP politicians.

Is Koizumi at a disadvantage again, since the LDP will use a full spec election? A major difference between last year is that Koizumi was brought in suddenly as minister of agriculture to shake up the status quo of Japan’s rice production, regulatory, and institutional apparatus.

Frustrations with the cost of living topped most surveys of voters’ concerns, and rice was a central concern of much media coverage of Japan’s rising costs. A compounding set of causes affected both the demand and supply of rice, leading to the price doubling in a year. Rising rice prices make for good news, since rice is a staple in most households. There was also an attractive media angle, since the seeming failings of the government, Japan’s agricultural cooperatives, and overall policies to limit rice production to keep prices high enough for farmers to make a living came to represent a visible manifestation of how Japan’s traditional way of doing things was failing the general public.

After a baffling gaffe, in which the previous minister of agriculture joked to his constituents that he never had to buy rice and could even sell some, the minister was forced to resign and Ishiba installed Koizumi to enact rapid efforts to combat rising prices. Koizumi accelerated efforts to release the government’s emergency supplies of rice. Koizumi’s decisive pronouncements and drastic actions ruffled the feathers of the LDP’s agriculture-oriented Diet members, but these moves were widely appreciated among the general public, and Koizumi received enormous amounts of media coverage. While rice prices did not decrease instantaneously, news coverage included retailers thanking Koizumi for moving quickly, and some rice farmers themselves feared that soaring rice prices could drive people away from rice consumption and hurt them in the longer run. How will the general LDP members who rejected Koizumi in favor of Takaichi and Ishiba vote this time? This very well may be the lynchpin in this election.

Japan’s new prime minister will face Japanese voters’ frustrations with the LDP that fueled its loss in the upper house elections. Voters were unhappy with the LDP for not addressing the core economic challenges they faced—both in the long term and in their immediate pocketbooks. A poll conducted by NHK, Japan’s national broadcaster, just before the July upper house election, shows that 29 percent of voters identified society security and declining birthrate as key issues they were focused on in the election, followed by 28 percent for measures to deal with rising prices. The other issues were in the single digits: dealing with the U.S. tariffs (8 percent), money and politics (8 percent), foreign affairs and security (7 percent), policies relating to foreigners (7 percent), name selection upon marriage (1 percent) and other (1 percent).

Other polls paint a similar picture. An exit poll taken during the election by Nippon TV found that the most important issues for voters were dealing with rising costs and economic policy (45.2 percent), social security and social safety nets (14.3 percent), policies around declining birthrates and supporting children (12 percent), followed by policies regarding foreigners (10.4 percent), political reform (6.6 percent), diplomacy and security (5.7 percent), and rice prices and agriculture (1.7 percent).

In the upper house election, the LDP was unable to effectively address these concerns. The rise of far right rhetoric focusing on anti-foreign sentiment which had been rising as a fringe movement in Japan was propelled into center stage as the far right party Sanseito both rode and amplified it. These dynamics will be explored further elsewhere, but they were not a major frustration that appeared in the polling just before the election or a major exit poll.

In the runup to the election, rather than providing a strong economic growth vision, Ishiba got caught up in policy discussions led by opposition parties promising handouts and subsidies to combat rising living costs. However, as the party responsible for Japan’s fiscal health, Ishiba could not promise drastic tax cuts, cash handouts, or subsidies at the levels that opposition parties promised. Instead, he was left with the worst of all worlds: no major proactive economic vision, small cash handouts that did not meaningfully address living cost increases, and a seemingly half-hearted effort to maintain fiscal austerity since he caved on an attempt to increase elder healthcare expense caps in the name of fiscal austerity. The Ministry of Finance, with authority to approve government budgets, remains an important force that the party in power needs to contend with; the ministry takes its job to protect Japan’s fiscal health seriously, and can run interference with normal budgetary processes, restraining the LDP from extravagant promises in exchange for passing some of its key budget items. Given these dynamics, the LDP was caught explaining the need for fiscal responsibility while also promising handouts, but at such low amounts that very few voters would consider them to be actual relief from rising living costs.

It didn’t have to be this way. As some observers point out, Ishiba did proclaim several proactive visions for regional economic revitalization in early 2025. Strangely, these visions disappeared almost entirely in the election campaign, perhaps out of concerns that they would alienate urban voters.

Japan’s new prime minister will face pressure to articulate an economic growth strategy that goes beyond piecemeal and half-hearted subsidies, cash handouts, and tax breaks. In periods of short-term prime ministership, Japan has a poor track record of being able to articulate and execute economic reform strategies; its boldest, most long-reaching reforms came at moments when the LDP just returned to power, as was the case of the Hashimoto Ryutaro administration in the late 1990s and the second Abe administration in 2012. Another reformer, Koizumi Junichiro, came to power when his predecessor, Mori Yoshiro, faced single digit approval rates and over 70 percent disapproval. Koizumi promised to break the LDP of its old way of doing things, expelling members who opposed his reforms. Koizumi ended up saving the LDP by promising to break it. Will the younger Koizumi be up to the task? Will the more conservative or far right LDP candidates?

Part of the difficulty facing Japan is that there is no easy economic answer to deal with the population’s frustrations. An extremely weak yen raises the price of imports. U.S. tariffs threaten large swaths of jobs, particularly in small and medium suppliers. Chinese goods, facing U.S. tariffs, are flowing into global markets, particularly in Asia, undercutting Japanese exports. Weaker economies around the world are reducing demand for Japanese goods and services. Japan’s fiscal deficit remains over 200 percent of its GDP. Its population is aging and shrinking rapidly. There are opportunities for Japan’s demographic trajectory, its rapidly maturing startup ecosystem is providing much needed flexibility and dynamism into its economy and labor force, and large companies are far more innovative and global than commonly understood. The challenge facing the next prime minister is enormous.

In the 2025 election, the big winners were new parties. The Sanseito, founded in 2020, gained the most, from one seat to fifteen. The Democratic Party for the People, initially founded in 2018 but which solidified in its current form in 2020, continued its trajectory of winning seats in the 2024 lower house election to win more seats in the 2025 upper house election. These new parties were conservative, with the Sanseito on the far right and the DPP on the conservative side. Their gains were primarily from younger voters.

One interpretation is that the LDP, which was rarely the party of choice for young voters to begin with, has lost its right-wing and very conservative voters to these new parties. Older opposition parties, in particular the Constitutional Democratic Party, joined the LDP in losing seats to the new, young, and conservative parties.

Returning to the LDP presidential elections, the runoff candidate Takaichi was the furthest right of all nine LDP candidates. One hypothesis is that if she wins this time, the LDP might recover some of its far right support. The far right Sanseito has hinted that it is open to a coalition with the LDP.

However, from an international perspective, a far right LDP or a coalition adding a far right party would likely come at the cost of Japan’s good relations with its neighbors. South Korea’s President Lee is facing likely domestic backlash against the United States due to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid of South Korean nationals in a Georgia factory, if he is pulled further left—a position that he maintained in the past that includes criticizing closer ties with Japan. A far right LDP Prime Minister is likely to increase tensions by asserting ownership and control over disputed islands and taking a far less apologetic stance on historical issues. Japan-China relations may suffer as well for similar issues of a more assertive stance on disputed islands, assertions of Japanese defense capabilities, and history issues.

Correction: The data in the “Beginning” column of Table 3 was incorrectly uploaded. It has been corrected.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan