I. Introduction

South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) was the marquee announcement to come from the Twenty-Sixth Conference of Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2021. Touted at the time as an innovation in climate finance, JETPs were introduced as a model of international cooperation and climate finance designed to help middle- and lower-income countries shift their energy systems away from fossil fuel reliance while emphasizing issues of justice and equity. The announcement in 2021 of the first JETP was agreed to by the governments of South Africa and the International Partners Group (IPG), composed initially of France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union. The Political Declaration on the Just Energy Transition in South Africa, which announced the parties’ intention to form the JETP, entailed the mobilization of about $8.5 billion from the IPG to accelerate South Africa’s decarbonization journey, with a particular emphasis on winding down the country’s reliance on coal-fired power plants (CFPPs).1 Leaders were quick to laud the ingenuity and potential of the framework as a “model of support for climate action from developed to developing countries,” in the words of South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.2 Three other countries have since followed South Africa in signing JETPs: Indonesia (at COP27 in November 20223), Vietnam (in December 20224), and Senegal (in June 20235). There were also discussions with India, but these discussions failed to result in a deal.6

In the years since the signing of the various JETPs, implementation has been slower than initially hoped. Yet many analysts urged patience given the challenges inherent to reform of the energy sector in any context, noting reasons for at least cautious optimism.7 Then Donald Trump returned to the White House. On January 20, 2025, Trump withdrew the United States for the second time from the Paris Agreement, and on March 5, he rescinded the United States’ commitments to South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam (the United States did not participate in the Senegal JETP).8 Given the U.S. withdrawal and somewhat laggard progress, it is reasonable to doubt that the once promising model will be able to achieve its ambitions. However, neither of these challenges fully captures the fundamental question facing JETPs at this juncture. Beyond navigating the U.S. withdrawal and accelerating implementation, sponsors and signatories are faced with deeper questions regarding the scope and ambitions of the platform.

Broadly speaking, there are two possible directions along which JETPs can continue to evolve. Along one path is a dedication to energy emissions reduction as the alpha and omega of the JETPs. This means narrowing the focus of the agreements to decommissioning CFPPs or closely related issues—measuring success through plant closures and reduction in carbon intensity of energy generation. Along the other path is a much broader conception of JETPs as vehicles for catalyzing broad economic transformation toward green energy and low-carbon industrial ecosystems. Success for this path would be measured in jobs created, additional capacity installed, and reliability of grid systems.

Financing requirements for planned objectives far outstrip available funds—even before the U.S. withdrawal—and the economic and humanitarian consequences of increasingly severe climate events continue to accelerate.

Elements from each of these branches are present to varying degrees across each of the four existing JETP arrangements, but in no instance does either option function as a paramount organizing principle. This is a challenge not because the specific objectives implied by each principle are always necessarily mutually exclusive, but because the varying ambitions for JETPs reflect deeper tensions between core constituents of the agreements. Given unlimited time and resources, both objectives could be pursued in tandem, but resources are scarce and implementation timelines are short. Financing requirements for planned objectives far outstrip available funds—even before the U.S. withdrawal—and the economic and humanitarian consequences of increasingly severe climate events continue to accelerate. If JETPs are to be successful, the relevant parties must come to a sharper understanding of what “success” entails. This requires confronting the questions of why IPG members are providing financing and what host countries can hope to achieve through these deals.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section II provides background and basic summary information. This includes a brief discussion of the origins of JETPs as a concept and a high-level presentation of the financing packages and priorities of the specific agreements. Section III identifies two sets of fundamental tensions at the heart of the overall JETP framework. These tensions reflect familiar discrepancies between the motivations and aspirations of IPG and host countries as well as country-specific implementation challenges. Left unaddressed, these tensions risk undermining the effectiveness of the agreements moving forward. Section IV develops the two broad pathways along which JETPs may continue to move forward. One option is a singular focus on decarbonization; the other is an expansive program of generalized economic transformation. Section V concludes with a brief summary and discussion.

II. Origins and Summary Information

The origins of JETPs as a model are found in South Africa. Although the concept of “just transition”—as used to express dual concerns regarding social justice and the environment—is generally considered to have arisen out of labor movements in North America during the mid-to-late twentieth century, South Africa has a deep history of engagement with the concept.9 In particular, labor representatives like the Congress of South African Trade Unions supported the just transition framing in linking efforts to combat climate change with the rights of the working class: “A ‘just transition’ means changes that do not disadvantage the working class worldwide, that do not disadvantage developing countries, and where the industrialised countries pay for the damage their development has done to the earth’s atmosphere.”10

More specifically, it was a South African think tank––Meridian Economics––that in 2018 developed the structure that would become the JETPs.11 Originally named the “Just Energy Transition Transaction,” Meridian’s proposal turned on their modeling work, which showed it was possible to remove a gigaton of carbon from the global budget at a rate below the market price of carbon.12 In September of 2019, Ramaphosa publicly introduced the Just Energy Transition Transaction concept at the United Nations secretary-general’s Climate Summit.13 The emergence of this proposal coincided with reforms at the South African state power utility, Eskom; the development of the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC); and South Africa’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) planning ahead of COP26.

Moreover, influential research on early retirement of coal assets produced by U.S. think tanks and financial institutions around 2020 also made the case that phasing out the global coal fleet could be done at a surprisingly cheap—or even net socially positive—rate in a relatively short time period.14 Much of their work focused on the United States and other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, but it also included discussion of emerging economies—including South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India—and the types of financial supports development financiers and multilaterals could provide to help expedite efficient coal decommissioning. This research received attention among policymakers in IPG countries and functioned as a complement to Meridian’s work in South Africa.

Both the specifics of the just energy partnership idea and the undergirding conceptual basis had deep historical roots in South Africa.

This is only a brief sketch of a much richer history, but the core takeaway is that both the specifics of the just energy partnership idea and the undergirding conceptual basis had deep historical roots in South Africa. Although the arguments for cost-effective coal decommissioning have gained traction within IPG countries, the JETP itself was not an idea developed by IPG members from scratch and then exported. South Africa emerged as the first JETP country in large part because of the nature of its CFPP fleet. At an average age of about forty years, South Africa’s CFPP fleet was far older than those of most countries outside of Europe and the United States (Indonesia’s figure is closer to ten years, for example).15 This lowered the cost of asset retirement in South Africa and made the financing scheme more viable.

Policymakers involved in the deal hoped that the agreement with South Africa could serve as a pilot for an innovative international climate finance program that could be scaled up and replicated across other middle-income countries. Indonesia, Vietnam, and Senegal signed during the initial flurry, but discussions of continued expansion into other countries have slowed to a halt. Although the specifics of the four JETPs vary markedly, the twin aims of efficient global abatement and management of transition impacts on vulnerable communities nonetheless remain a shared staple. Before outlining the details of the deals themselves, we first discuss the actors on the other side of the arrangements: the IPG.

Composition of the International Partners Group

IPG membership varies by JETP. For instance, in the South Africa deal, the IPG originally comprised the United Kingdom (chair), the European Union, France, Germany, and the United States, but Denmark and the Netherlands joined later and Canada, Spain, and Switzerland made commitments while remaining formally outside the IPG. In Indonesia’s case, the IPG comprised the United States (co-chair), Japan (co-chair), Canada, Denmark, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, and the United Kingdom. For the Vietnam JETP, the European Union (chair), Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States constitute the IPG; and in Senegal’s case, the IPG includes France (chair), Germany, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Canada (see table 1).

In addition to the countries, the other important financing actor—in the case of Indonesia and Vietnam specifically—is the private sector, represented by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). While crowding in private capital is not unique to the JETP plans of Indonesia and Vietnam, what distinguishes the role of GFANZ in these cases is the intention for the alliance to provide half of the headline funding amounts. The following sections outline the scale and nature of these commitments, and explore the implications of GFANZ involvement given the evolution of political dynamics since the signing of the various originating declarations.

Finally, the World Bank Group and other multilateral development banks (MDBs) play a key role in directing financing from IPG members and facilitating project implementation. One-fifth of IPG funding to Indonesia is packaged as guarantees for World Bank loans. The Climate Investment Funds (CIF)—an umbrella organization for two World Bank financial intermediary funds (FIFs), the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) and the Strategic Climate Fund—is the single largest contributor in South Africa’s Investment Plan. CIF funding is earmarked under the Accelerated Coal Transition platform (CIF-ACT), which was established in 2022 to distribute funding for early retirement efforts in six countries with pronounced coal dependence.16 Along with the Asian Development Bank and other World Bank FIFs, CIF-ACT is a major funder of Indonesia’s Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM), which oversees more than $2.5 billion for accelerated coal-fired power retirements.17

Significant contributions from the United States, Canada, and Denmark, among other IPG members, were channeled through the CIF-ACT platform and thus not reflected in individual country commitments. Former U.S. president Joe Biden’s administration, for instance, directed a $950 million, first-of-a-kind Treasury loan to the CTF in 2022, and Canada contributed $400 million earmarked specifically for CIF-ACT programs.18 The World Bank’s involvement also includes implementation guidance and technical assistance, with MDB officials co-chairing Indonesia’s JETP Secretariat Policy Working Group and sitting on the Technical and Just Transition Working Groups. Each JETP relies heavily on involvement from the World Bank and regional MDBs, underscoring the intermediaries’ roles as both key financiers and implementation partners.

Scale of Financing and Types of Projects

The first major milestone for JETPs following the signing of political declarations is the development of the investment plans meant to define the objectives and intended use of funds. South Africa released its Investment Plan in November 2022 (and one year later its Implementation Plan), followed by Indonesia’s Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan (CIPP) in November 2023 and Vietnam’s Resource Mobilization Plan (RMP) in December 2023 (Senegal, as the latest country to join the JETP, has not yet released a commensurate investment plan).19 The South Africa deal originally carried a headline figure of $8.5 billion, but later additions have brought the total value of international pledges to around $12.8 billion.20 For South Africa, the finance package is varied, but overwhelmingly public, with about 70 percent sourced directly from sovereign bilateral partners and the rest from MDBs. In contrast, private sector contributions from GFANZ constitute half of both Indonesia’s and Vietnam’s $20 and $15.5 billion headline figures. Senegal’s package is modest by comparison, coming in at $2.7 billion.21 Figure 1 summarizes the IPG commitments (not including GFANZ) across South Africa’s, Indonesia’s, and Vietnam’s JETPs as outlined in the CIPP, the RMP, and the most recent data from South Africa’s JET Grants Register.

There are a few considerations to note in figure 1. First, South Africa’s $12.8 billion figure reflects the current total following the United States’ withdrawal. Between the release of the Implementation Plan in 2023 and the most recent Just Energy Transition Funding Platform Data for Q1 2025, the United States withdrew its commitment of just over $1 billion, but Germany increased its commitment by around 50 percent, bringing it to about $1.8 billion (with the greatest composition of grants and concessional finance among funders), and multilateral financiers like the World Bank and African Development Bank (AfDB) similarly scaled up commitments.22 Additionally, the large outlier of Spain’s contribution to South Africa is explained by the provision of export credits valued at $1.89 billion, constituting over 80 percent of Spain’s total contribution.

Secondly, while South Africa and Indonesia’s financing is sourced from a relatively balanced set of partners, Vietnam’s figures lean more heavily on a few contributors. Moreover, while concessional loans make up 50 and 60 percent of South Africa’s and Indonesia’s packages respectively, the corresponding figure is only 33 percent for Vietnam. In no case do grants and technical assistance constitute more than 5 percent of the IPG offer.

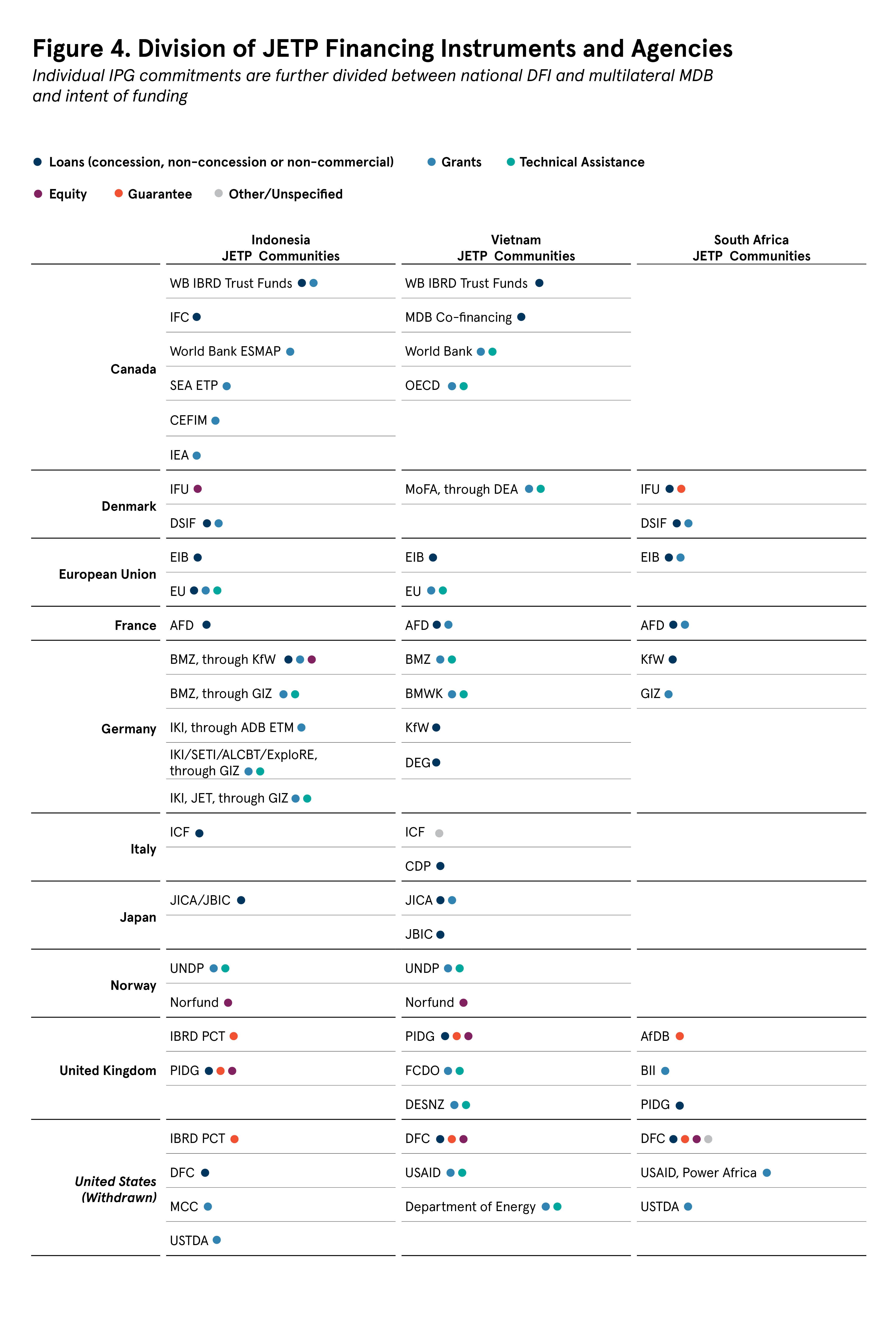

Variation in the nature of financing across deals and between countries reflects the heterogeneity of actors involved. Not only does the IPG not present a syndicated offer as a group, but even individual commitments from donor countries are pledged from a variety of different institutions. For example, in South Africa’s case, France offers both grants and loans through the Agence Française de Développement; Germany offers grants through Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, but concessional loans through Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau; the United Kingdom’s financing is at least partly channeled through a partnership with the AfDB; and the United States offered grants through its Trade and Development Agency, Agency for International Development, and Power Africa, as well as support for private-sector financing from the Development Finance Corporation. Figure 4 (see annex 1) presents a glimpse of the constellation of actors.

Far from the simplicity implied by headline announcements, the landscape of actual financial commitments is an extraordinarily complex assemblage of dozens of actors, each with their own priorities and operating procedures.

Far from the simplicity implied by headline announcements, the landscape of actual financial commitments is an extraordinarily complex assemblage of dozens of actors, each with their own priorities and operating procedures. The CEO of the African Climate Foundation, based in South Africa, identified the transaction costs involved with needing to negotiate separately with IPG members each beholden to their own interests and political mandates as a headwind to progress.23 Another related obstacle is that architects of host country policy planning are frequently forced to navigate funder conditionalities like localization provisions, which themselves differ across financing entities. This challenge is not unique to South Africa: Over half the funds in Indonesia’s package and around 20 percent in Vietnam’s were contingent on particular conditions if not outright earmarked for specific projects.24

Objectives of Country-Specific JETPs

Beyond variation in the sources and composition of financing, the objects of each JETP differ in important ways. Senegal stands out for both its lower headline financing and its narrow aims. Part of the explanation for Senegal’s more modest headline figure is the country’s comparatively low baseline of energy generation, and by extension, carbon emissions. Details are yet to be released, but the main stated aim of the Senegal program is to increase the share of renewable energies in installed capacity to 40 percent of the electricity mix by 2030.25

Planning documents for the other three JETPs are more expansive. In addition to the electricity sector, South Africa’s Investment Plan also places a heavy focus on new energy vehicles, green hydrogen, and municipal development.26 Indonesia’s CIPP identifies five investment focus areas—including transmission expansion and renewable energy supply chain enhancement—and Vietnam’s RMP outlines commitments to technology transfer and energy efficiency (see table 2).

Summing up the first two columns, the objectives of the Implementation Plan and the CIPP are estimated to require at least $98.3 and $97.2 billion in South Africa and Indonesia by 2027 and 2030 respectively. Vietnam’s RMP was developed to support the country’s Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8), which carries a projected financing need of $134.7 billion by 2030.27 Although Vietnam’s JETP and PDP8 projects do not overlap precisely, the estimated requisite additional aid and foreign investment for the energy sector alone is $46.1 billion.28 Therefore, for South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam the total financing package from the IPG represents about 13, 20, and 33 percent respectively of the projected needs outlined in the primary JETP planning documents, and that is counting contributions from GFANZ in the latter two cases. While the JETPs’ architects did not intend for the deals to cover 100 percent of the costs, the large gulf between resources and ambition—and questions concerning the extent to which domestic resource mobilization will be able to fill the gap—remains notable.

Two points arise from table 2 and figure 2. First is the clear discrepancy between the cost of achieving the ambitions laid out in the various planning documents and the headline commitments. The shortfall is clear even before considering issues of disbursement or the uncertain nature of GFANZ funding. In some cases, even the public funding is contingent upon commitments of private capital and is therefore uncertain. Bridging the gaps between ambition and commitments via domestic spending will be difficult given existing debt burdens and competing demands for public finance.29

The second point worthy of highlighting is the relatively small allocation of funding for justice-related projects. The Framework for a Just Transition Report prepared by the PCC cites a need of at least $10 billion for “climate justice outcomes” over the next three decades in South Africa.30 While including only the $0.18 and $0.2 billion amounts for Skills Development and Just Transition in table 2 would be an undercount, it is clear that projects aimed at ensuring justice constitute only a minute share of total spending. The simplest and strongest evidence for this is the small share of grant funding—about 4 percent, 3 percent, and 4 percent of total funding in South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam respectively. Although the relationship between grants and justice programs is not one-to-one, the two are closely linked, and thus the former serves as a proxy for the latter. If anything, grants are likely an overestimate because they may be used for reasons other than transitional justice programs, whereas these programs—which generally do not entail commercial returns—could not be funded by loan mechanisms. A recent academic analysis examining the existing JETPs concludes that South Africa’s financing package “provides insufficient just transition funding” and notes that the CIPP and the RMP “do not outline specific figures for the just parts with the risk of diminishing it to mere performative rhetoric.”31

Justice comprises not just social service and transfer payments but also procedural transparency and the fostering of participation by impacted communities.

National-level energy infrastructure is a big-ticket item, so to be fair, measuring spending relative to that quantum can belie the size of absolute amounts. Moreover, justice comprises not just social service and transfer payments but also procedural transparency and the fostering of participation by impacted communities. On this front, South Africa, through the Presidential Climate Commission, has done a credible job of bringing a wide set of voices to the table and fostering meaningful dialogue, including producing a critical appraisal of the country’s Investment Plan in May of 2023.32 Officials in Indonesia and Vietnam have arguably shown more focus on actualizing the project pipelines identified by their respective JETP Secretariats, rather than implementing associated justice-oriented programming. Indonesia’s CIPP makes mention of justice considerations and outlines some associated actions, but the core investment focus areas exclusively pertain to transmission expansion, coal asset retirement, new renewable energy installations, and supply chain enhancements. Vietnam’s RMP similarly aims to foster new domestic renewable energy industries, with provisions focusing on technology transfer and added manufacturing.

One cannot escape the fact that for a finance deal operating under the moniker just, remarkably little finance is devoted to explicitly justice-focused initiatives.

Overall, one cannot escape the fact that for a finance deal operating under the moniker just, remarkably little finance is devoted to explicitly justice-focused initiatives. In the three years since the launch of South Africa’s JETP, attention has increasingly moved away from the justice focus. The second pillar of the initial Just Energy Transition Transaction proposed by Meridian called for “catalytic financing for a ‘Just Transition Fund’ to support coal workers and affected communities and assist in developing an alternative economy for Mpumalanga coal province.”33 Meridian later suggested that catalytic financing—a moniker for grants and concessional finance—should account for at least one-third of total financing.34 As commitments stand, available catalytic financing from IPG members falls far short of what is needed to achieve the ambitions of host countries as set out in the core planning documents or original just-transition theories. As we examine in the following section, these stylized facts reflect fundamental tensions at the heart of the JETP model.

III. Fundamental Tensions

As highlighted in the introduction, the abstract concept of the JETP model has a compelling internal logic. IPG countries can achieve high abatement impact per dollar while host countries receive financial support to help ease the impacts of a transition to a low-carbon energy system on affected communities. However, in practice, there exist at least two fundamental and closely linked sets of tensions not captured by the abstract logic of the deal. These tensions are rooted in differing conceptions of the responsibilities implied by the legacy of historical emissions, the landscape of contemporary energy consumption and emissions patterns between IPG and host countries, and domestic political economy complexities.

Legacy Tensions: Historical Culpability and the Burden of Transition

Although novel in institutional form, JETPs are still international climate finance, and as such, they are subject to what may be termed “legacy” tensions: perennial, foundational issues and debates that reappear in essentially every instance of climate finance collaboration, regardless of form.

JETP host countries tend to view the provision of finance from IPG states as a means of addressing historical inequities in carbon emissions, whereas IPG states tend to avoid this reparative framing.

The first tension here concerns the salience of historical emissions. JETP host countries tend to view the provision of finance from IPG states as a means of addressing historical inequities in carbon emissions, whereas IPG states tend to avoid this reparative framing.35 While this tension is not unique to South Africa, this framing is particularly salient in that country’s core JETP documents. Definitions of distributive and restorative justice respectively used in South Africa’s Investment Plan include statements that “burden of transition . . . and the costs of adjustment are to be borne by those historically responsible for the problem,” and “historical damages . . . must be addressed with a particular focus on redress.” In his opening message to the Implementation Plan, Ramaphosa called upon the “historic and continuing polluters of the world” to meet their financial commitments.36

The nature of the motivation is relevant for the composition of finance for each JETP. If, as South Africa’s JETP Joint Statement asserts, the purpose of the JETP is at least in part to redress inequities, then the IPG offer ought to comprise largely grants, or at least highly concessional loans. As outlined in Section II, this is clearly not the case, as grants represent under 5 percent of total finance in South Africa’s deal, and slightly less for both Indonesia and Vietnam. The disconnect in expectations led to initial distrust between South Africa and the IPG and ultimately was a contributing factor to the premature collapse of India’s proposed JETP.37

Frustration arising from delayed finance and its commercial packaging illustrates a core asymmetry between IPG funders’ investment strategy and host countries’ reparative expectations. The majority share of commercial financing in the IPG offer implies an investment calculus that is distinct from the provision of no- or low-return grant funding or concessional finance. In other words, the IPG packages are focused on mobilizing forward-looking financing rather than providing no-strings-attached funding to remedy historical culpability. IPG members clearly did not envision JETPs as platforms for reparation (a function they likely reserved for the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage). This contrasts clearly with the expectations espoused by South Africa, but less so in the cases of Indonesia and Vietnam where the emphasis on restorative justice was far less explicit.

Indonesia’s Joint Statement, for example, underscores a core IPG goal to “enable the accelerated decarbonization of Indonesia’s power sector to achieve the most ambitious emissions cuts possible.”38 The statement also calls for new emissions reductions targets, emphasizes the domestic ban on new on-grid coal-fired capacity (Perpres 112/2022), and calls for restrictions on new off-grid coal-fired capacity. While these policies are well-intentioned, they are largely prescriptive and impose restrictive conditions on available financing, an approach that runs contrary to the idea that JETP funding is reparative. Based on the composition and allocation of funds between focus areas, IPG members view JETP platforms as a vehicle to aggregate private investments in coal decommissioning, new renewable energy, and associated infrastructure.

Ultimately, the question of whether JETPs are a means of rectifying historical inequities or of accelerating the buildout of renewable energy systems translates into whether the purpose of the financing package is to provide grants and concessional loans or to find inroads for capital from IPG countries. Either is possible, and both can be useful ambitions, but their parallel existence under an imprecisely defined umbrella will lead to continued frustration and lackluster progress.

The second, perhaps more volatile, legacy tension relates to the emissions intensity of participating countries’ energy systems—host and donor alike. South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam emerged as natural targets for JETP arrangements because of their relatively high-emitting energy sectors, a function of heavy reliance on coal power for electricity generation. South Africa is the continent’s largest CO2 emitter and the world’s eighteenth-largest overall, while Indonesia is the world’s sixth-largest emitter, with energy sector emissions growing faster than energy demand over the past decade.39 Meanwhile, coal-fired power represents 43 percent of Vietnam’s total energy mix, and emissions have increased 548 percent since 2000.40 And yet when it comes to reliance on fossil fuels, JETP host countries are comparable to IPG members, and total per capita emissions are generally lower in host than in IPG countries (see figure 3).

In 2022, South Africa had the highest percentage of fossil fuels in total energy supply among the countries plotted in figure 3 (93 percent), but this was not considerably more than Japan (87 percent), the Netherlands (83 percent) or the United States (81 percent).41 Moreover, on a per capita basis, Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, Germany, and Japan were each higher emitters than any host country, and Vietnam and Senegal were the two lowest on this metric among the group overall.42

To some, JETPs presented an agile alternative to large multilateral bodies often bogged down with debates over emissions inequities.43 A minilateral model with self-selecting donors and recipients could, in theory, cut through the bureaucracy of organizations like the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to rapidly identify projects and mobilize funding. And yet, the original JETP document—South Africa’s Joint Statement—puts emissions issues front and center. The basic fact that the emphasis on transitioning falls on host countries despite IPG members’ own high greenhouse gas emissions contributes to the second unavoidable tension underlying the framework.

Developed nations cannot entirely skirt the reality that they benefit from centuries of coal-driven industrialization. And this reality gives rise to the criticism that the energy transition is being foisted upon host countries by those who are themselves still reliant on fossil fuels.

Even factoring in Europe’s rapid coal retirement—led by Germany’s accelerated phase-out goal and the United Kingdom’s complete coal drawdown—developed nations cannot entirely skirt the reality that they benefit from centuries of coal-driven industrialization. And this reality gives rise to the criticism that the energy transition is being foisted upon host countries by those who are themselves still reliant on fossil fuels. For example, in mid-2023, the influential South African Minister of Mineral and Petroleum Resources Gwede Mantashe decried the idea of a just energy transition as a foreign concept and claimed South Africa “cannot work on the basis of a program developed in the Developed North.”44 The potency of the charge of “foreign concept”––despite, as outlined in the preceding section, the JETP model having roots in South Africa—speaks to the challenge inherent in the dynamics of energy consumption and emissions.

This tension is evident in the core planning documents themselves: The third chapter of the CIPP, meant to contextualize Indonesia’s decarbonization journey, opens with figures placing the country’s 2020 per capita carbon emissions in the context of other G20 members as well as comparing cumulative emissions since 1850 among advanced economies.45 This speaks to the drafters’ awareness of both contemporary and historical dynamics of emissions generation globally.

Implementation Tensions: Balancing Priorities and Domestic Political Economy

Beyond the suite of underlying legacy tensions, the challenge of “transitioning” energy systems in host countries is compounded by country-specific conditions like existing infrastructure limitations, rapidly growing demand, and most importantly the dynamics of local political economies.

In South Africa, scheduled power cuts—known as “load-shedding”—began occurring in 2007 and have continued sporadically, though the situation seems to have improved starting around early 2024.46 Load-shedding was particularly acute in 2021 through 2023, especially unplanned outages, with the South Africa Reserve Bank estimating direct negative impact on annual GDP growth to be between 0.7 and 3.2 percentage points.47 The resultant political backlash from power cuts is commonly cited as a key reason the African National Congress failed to win a majority in the country’s 2024 general elections for the first time since the end of apartheid in 1994.48 Ensuring consistent, reliable energy access will be a key benchmark of success against which the coalition Government of National Unity will continue to be assessed.

Additionally, the extended coal value chain provides employment for tens of thousands of South Africans, especially in the Mpumalanga region, which already experiences higher than average unemployment.49 Skepticism toward the transition away from coal is therefore an important political dynamic in the region, especially given the salience of powerful coal unions. The political presence of unions, both in coal value chains and more generally, is likely an important factor in explaining the heavy emphasis on justice and labor concerns in South Africa’s JETP documents relative to the others.

In Indonesia, industrial policy designed to stimulate added-value processing and manufacturing industries for the country’s vast nickel reserves has led to significant increases in energy demand, up about 50 percent in 2023 compared to 2020, when an export ban on raw nickel was reinstated.50 New coal-fired capacity has met the majority of load growth, with annual coal generation increasing from 181 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2020 to 217 TWh in 2023.51 Given Indonesia’s inherently fragmented transmission network and the geographic sprawl of nickel reserves and processing infrastructure, new industrial clusters lack access to the reliable grid connection, leading to fivefold growth in captive CFPP generation from 2.3 gigawatts (GW) in 2014 to 11.2 GW in 2023.52 These installed captive coal assets will remain online until viable interconnection alternatives are made available, a reality that forced the Indonesian JETP Secretariat to exclude captive emissions from reduction targets set in the CIPP. When combined with the country’s data center development strategy, energy demand is set to continue its steep upward trajectory through 2030, despite slow-moving investment in new renewable energy and enabling infrastructure.53

In the midst of dramatic load growth and industrial sprawl, the central role of Indonesia’s state-owned utility and energy developer, Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), appears to be changing. PLN’s latest resource plan—which informs the JETP Secretariat’s project pipeline—outlines a greater role for independent power producers, creating avenues for stronger competition in project development. This is an essential evolution to enable Indonesia’s long-term energy transition, but the effort is complicated by general inefficiency and strong ties between government officials and private industry.

PLN’s common “take-or-pay” contract structure results in Indonesia’s Treasury bearing the costs of excess electricity generation. Indonesia’s grid reserve margin—the measure of excess supply—currently stands at slightly below 50 percent above maximum demand.54 The glut is partially due to a building spree that commenced under the previous administration and continues to complicate efforts to transition away from high-emitting assets. Despite the oversupply of existing capacity, efforts to mothball existing assets or add new renewable capacity to the grid are complicated by the web of connections between Indonesian investors in coal-fired power and siting members of government. For example, the current minister of state-owned enterprises, Erick Thohir, is the brother of the president, director, and CEO of PT Adaro Energy, one of the world’s largest coal miners, which is currently developing a 2 GW coal-fired power plant.55 President Prabowo Subianto also has interests in PT Nusantara Energindo Coal, a developer pursuing projects in North Kalimantan. Given the legacy of state-owned assets and public-private relationships, retirement-focused initiatives will continue to run up against ingrained domestic political economy realities in Indonesia and attempts to install new renewable capacity will struggle.

Questions of which energy sources to pursue and how to manage the attendant trade-offs speak directly to core issues of economic development and ultimately, sovereignty.

More than environmental issues or a techno-scientific constrained optimization problem, questions of which energy sources to pursue and how to manage the attendant trade-offs speak directly to core issues of economic development and ultimately, sovereignty. Reliable energy generation and distribution matter for both individuals’ quality of life and economic activity. Energy is crucial for the development of industry, especially if the aim is to compete internationally.56 Policymakers in host country governments understand the global imperative to move toward a decarbonized future, but they are also beholden more proximately to the national interests of energy security and economic development.

These twin sets of tensions—differing conceptions of historical responsibility and the contemporary landscape of fossil fuel reliance combined with domestic political economy complexities—combine to exert centrifugal pressure at the heart of JETPs. At a moment when the ecosystem of international climate finance is undergoing significant disruption and countries around the world are resorting to energy security orientations, these tensions require direct confrontation.57 The final decision on where to take each JETP resides with the host countries and IPG members, but we argue there are, broadly speaking, two paths forward: a narrowing of remit and ambition to focus solely on decarbonization through decommissioning, or a broadening of the framework as a vehicle for comprehensive economic transformation predicated on energy expansion. Section IV develops each option in turn.

IV. Pathways for Future Partnerships

The tensions described in the preceding section predate Trump’s return to the United States presidency. Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the three JETPs to which it was party is a shock to the system, but ultimately, the United States government was never the center of gravity for these arrangements. As shown in Section II, U.S. commitments constituted only about 10 percent of the total JETP pledges from the IPG, and the composition of U.S. commitments was not particularly high quality––the vast majority was in the form of non-concessional loans and debt guarantees, with slow disbursement being a noted feature.58

Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the three JETPs to which it was party is a shock to the system, but ultimately, the United States government was never the center of gravity for these arrangements.

What is of greater consequence than the U.S. public withdrawal from JETPs is the wider systemic damage to the surrounding structural context. Trump’s return to the White House coincides with a deep backlash across the U.S. Republican party against climate change mitigation and environmental and social governance issues broadly.59 Under direct threat from a politicized U.S. Department of Justice, several leading financial institutions promptly withdrew from the Net Zero Banking Alliance, GFANZ’s internal body responsible for setting climate-aligned standards for lending and investment, for fear of reprisal.60 Whether or not the alliance’s commitments will still materialize is an open question at best. For Indonesia and Vietnam, the collapse of GFANZ threatens to erode half of the committed funding that had served as the basis for careful planning in the CIPP and RMP.

Beyond the highest-level financing commitments, many of the supporting actors involved in implementing the JETPs have been impacted by decisions taken by the Trump administration. The White House’s recent budget proposal entails cutting a $275 million contribution to the Global Environment Facility and the Climate Investment Funds, the latter of which figures into both South Africa and Indonesia’s financing packages.61 Although fears of complete U.S. withdrawal from the World Bank were allayed during Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s speech at the 2025 Spring Meetings, he made it clear that the United States intends for the World Bank to refocus on core principles, of which it is safe to infer energy transition is not one.62

Thus, while the withdrawal of the United States and damage to other supporting institutions is not fatal, this moment nevertheless provides an impetus to reevaluate the JETPs’ ambitions. Confronted with this moment, host countries and IPG partners face two broad pathways forward: narrow focus to CFPP decommissioning, or opening up JETPs as vehicles for generalized energy-based economic transformation. Table 3 presents a high-level comparison of the two options, and we then expand on each in turn.

Option 1: Double Down on Decommissioning

One option is to double down on emissions reduction as the sine qua non of the JETP. This means staying rooted firmly in the United Nations framework, anchoring programming on alignment with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and focusing more or less exclusively on CFPP decommissioning. Taking this route means accepting that the United States and many (though not necessarily all) private financial actors will not be involved at least until 2029, and possibly further into the future.63 At any rate, reengagement by that time would be functionally too late from a mitigation perspective. Taking this path very likely means putting aside other objectives, like the development of a new energy vehicles in South Africa or supporting transmission system expansions in Indonesia, at least under the umbrella of the JETP financing arrangement.

Maintaining a focus on emissions mitigation will entail reliance on public finance from the remaining IPG members.

Maintaining a focus on emissions mitigation will entail reliance on public finance from the remaining IPG members. To their credit, Japan and Germany were quick to signal their intent to co-lead the Indonesia JETP following U.S. withdrawal.64 Yet it would be a mistake for host countries to plan on the remaining IPG countries providing finance on the scale required to substantively move the needle on all of the objectives described in the respective investment plans.

The legacy of Global North–Global South climate finance is not encouraging in general, and IPG countries currently face myriad other demands on their fiscus, from increasing defense spending in Europe to grappling with reverberations from global trade shocks in the wake of ever-changing U.S. tariffs.65 Furthermore, even if IPG countries want to continue and scale up their support for international climate initiatives, the financing needs arising from the vacuum left by the steep decline of U.S. aid and multilateral agencies mean there are many competing demands for financing outside of JETPs. These same basic dynamics are at play for the MDBs and philanthropies that have supported the JETPs thus far.

Within this context of lower overall resources under the JETP arrangement, the objectives will need to be carefully calibrated. Along this pathway, IPG funding would focus primarily on supporting the “just” aspects of transitioning from reliance on coal—job retraining programs, other forms of social support, and continued cultivation of the institutional ecosystem managing dialogue among domestic constituents. Crucially, this finance should be predominantly in the form of grants, or highly concessional loans. For the IPG members, adopting this approach implies leaning into the historical culpability line of argument and constitutes an act of moral redress.

For host countries, taking this path would reflect a strategic choice to silo the ramp-down of their coal fleets from wider energy and economic development priorities, relegating collaboration with the IPG only to the former. The upside of this trajectory would be access to additional fiscal space to manage the disruption effects of impacted coal communities while maintaining total flexibility of decisionmaking on all other aspects of the programs outlined in various national planning documents, like the Renewable Energy Masterplan in the case of South Africa.66 The downside would be loss of built-in access to larger-scale public and private finance. However, relevant organs of the JETP institutional infrastructure developed to support large-scale project development—like the Just Energy Transition Funding Platform in South Africa—could be retained, but should shift focus from JETP finance to other sources, like domestic capital markets.67

Option 2: Energy Expansion and Economic Transformation

The alternative option is for JETPs to evolve into a program of international engagement for energy expansion, rather than direct emissions reduction. This would entail shifting the principal focus away from CFPP decommissioning and NDC targets, and placing energy access, renewable capacity expansion, and system reliability at the core, as well as retaining the broader green industrial aspirations. IPG financing could be more flexible on innovative energy and industrial investment opportunities—supporting next-generation geothermal, nuclear, and long-duration storage energy projects alongside novel low-emissions material processing and manufacturing facilities. Depending on interest and institutional capacity in host nations, tandem programs could solidify project pipelines for transmission and distribution infrastructure with grid enhancement technologies. The aim of these focus areas should be to establish an investment environment wherein clean energy technologies are able to outcompete legacy thermal assets—eroding the viability of CFPPs without focusing directly on early retirement.

Focusing on the growth opportunities—energy or otherwise—outlined in the investment plans rather than solely scale-down and transition management offers the potential of attracting finance on the scale required to fulfill the ambitions outlined.

Focusing on the growth opportunities—energy or otherwise—outlined in the investment plans rather than solely scale-down and transition management offers the potential of attracting finance on the scale required to fulfill the ambitions outlined across the various planning documents. Non-concessional finance from the private sector can be useful for host countries when it is invested in productive activity that generates sufficient economic returns. Access to international capital markets is often a challenge for lower-income countries, especially African countries, because of risk perceptions or insufficient pipelines of “bankable” projects.68 The institutions that have emerged in host countries around JETP—secretariats, inter-ministerial committees, civil society engagement fora—offer a mechanism for overcoming some of these challenges. In addition to technical project pipelines, the JETP ecosystem can also play (and has played) a critical role in addressing the domestic political economy challenges that will inevitably arise.

Beyond private markets, prioritizing flexible energy generation aligns with emergent World Bank positioning, with implications for both finance and technical assistance.69 There is even the possibility that this pivot would result in reengagement by the United States. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright has emphatically noted his openness to engagement with African countries on expanding their energy systems.70 The White House’s recent draft language for reauthorization of the Development Finance Corporation advocates for investments in energy security abroad, and the State Department committed to fulfilling the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s power sector contracts. Shedding JETPs’ sole focus on coal retirement could induce reengagement from U.S.-based financial actors looking for commercial returns.71

For host countries, the benefits of this path are obvious: access to capital at scale—complemented by technology transfer—for the purpose of transforming their economies on the basis of a firm energy foundation. But there are also risks and trade-offs inherent to such an expansive partnership. Transaction costs of engagement with a wide set of actors would remain high, and some degree of compromise would likely be inevitable in liaising with public and especially private financiers at scale. Though less acutely and overtly, communities tied to legacy assets would still face disruption over the medium term, and these challenges would need to be addressed, principally through domestic spending.

For IPG countries, even the prospect of moving away from direct emissions reduction via coal retirement may initially strike some as a betrayal of the foundation of the JETP itself. If done well, this need not be the case, however. For one, an expansionist agenda is not necessarily incongruent with a mitigation imperative, as in most cases, the underlying economics favor renewables.72 This economic logic will only be further strengthened by the implementation of schemes like the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.73 Crowding investment into next-generation technology like nuclear and geothermal at scale in some of the fastest-growing countries on the planet—and supporting local innovation clusters through technology transfer—is arguably a more stable strategy for reducing emissions over the long term than a first-order focus on reducing legacy assets. Additionally, host country governments and communities are not unaware of the damages that arise from emissions, either economic or ecological. But when the choice is between being able to power one’s own home (or factory) or not, the generation source will always be a secondary priority.

V. Conclusion

The future of JETPs is uncertain. They arose as the product of creative policy innovation coupled with the priorities of high-level pronouncements coincident with the United Nations–led paradigm of net zero targets and sustainable development goals. Early growing pains related to building up institutions and coordinating across dozens of organizations made progress slower than anticipated, but ultimately these are surmountable challenges against which significant progress has been made. Beneath the surface, however, fundamental normative tensions pertaining to the spirit of the arrangement have never truly been resolved. These tensions predate Trump, but the effects of his return have brought them to the fore. The withdrawal of United States from the IPG is not as impactful as the withering of GFANZ resulting from fears among U.S.-based financial firms of backlash from administration and other Republican officials. Similarly, the ability of other supporting actors, from MDBs to philanthropies, has been constrained, either directly or as a result of their need to fill gaps elsewhere.

Beneath the surface, . . . fundamental normative tensions pertaining to the spirit of the arrangement have never truly been resolved.

Confronted by these challenges, the JETP project faces a crossroads. Along one path is a narrowed focus on CFPP decommissioning. Taking this choice means acknowledging that the United States, and much of the financial world, will not be involved. Acknowledging historical culpability, the remaining IPG members can reaffirm their commitment to decarbonization along the NDC-governed pathway as the principal and sole purpose of the JETP. To do so, they must align programming accordingly, providing grants or highly concessional financing along with technical assistance as needed to help soften the socioeconomic impacts of this decommissioning, as a means for redressing asymmetries in historical carbon emissions. This should be done openly as the stated purpose of the program, not an implicit underpinning. Host countries would benefit from support in managing the political and economic disruptions of transition away from coal while retaining full autonomy over other aspects of their energy and industrial priorities at the expense of streamlined access to large-scale capital.

Alternatively, JETPs could evolve from energy conversion to energy expansion programs. Embarking along this pathway would mirror a broader global evolution of the energy paradigm toward one of security rather than one of transition. Instead of the speed by which coal plants are brought offline, success would be measured by clean energy generation and access metrics, as well as achievement of the ancillary green industry objectives evinced across the investment plans. Under this frame, there is some reason to believe that the United States may reengage, but more importantly there is hope for greater involvement from the financial sector. Rather than navigating the delicate issue of energy-rich countries asking energy-poorer ones to take capacity offline, an expansionary agenda allows all parties to engage under a common objective. In the longer term, accelerated renewable generation and green industry still aim to support emissions reduction, but through a broader set of additive, development-oriented objectives.

The latter approach allows for greater flexibility and, most importantly, national agency in energy and industrial development. It fits well within the broader “country platform” model that is gaining traction following recent announcements from Bangladesh, Barbados, Brazil, Egypt, and Colombia, among others.74 Recent research and analysis on the potential of the country platform model abounds, but the throughline between most findings is the need for national ownership over planning and project identification.75 Rather than the top-down imposition of retirement goals and emissions reduction targets, a more flexible approach wherein national planning agencies develop investment plans in support of broader developmental objectives could help to resolve the fundamental tensions at the heart of JETPs. Allowing the varied forces of domestic political economies to set the objectives of investment removes the potential for (or perception of) international overreach.

The evolution of the JETP model has already begun to trend toward the “energy expansion” or “country platform” approach.

In many ways, the evolution of the JETP model has already begun to trend toward the “energy expansion” or “country platform” approach. While South Africa’s JETP included specific justice-oriented language intended to remain a core consideration throughout implementation phases, Indonesia and Vietnam are quickly diverging toward nationally determined commercial investment models. In each of the latter cases, JETP project pipelines are increasingly aligned with state-owned utility resource plans—in Indonesia’s case, PLN’s RUPTL, and PDP8 for Vietnam.76 In this sense, each JETP Secretariat acts as an interlocutor and clearinghouse between international financiers and domestic authorities.

Ultimately, the decision of which path to follow lies with the JETP members themselves. Those who are actually seated in the secretariats and ministerial committees, and the IPG negotiators, are the ones who know truly how effective the JETP architecture is, and the potential it has. Whatever the choice—which may differ by country—it is crucial that all parties are fully bought in to the path forward. The success of JETPs is essential not only for their participating countries, but for their value as precedent, particularly for stand-alone country platforms. Either a modest but accomplished agenda or a broadly-defined, open-ended process that defies discretization is preferable to a disjointed combination of the two that leads to yet another disappointment in the annals of international climate finance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Zainab Usman and Leonardo Martinez-Diaz for their invaluable guidance. We would also like to thank Katie Auth for her excellent feedback on an earlier draft.

Annex 1: Figure 4

Notes

1“Political Declaration on the Just Energy Transition in South Africa,” Federal Government of Germany, November 1, 2021, https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/1974538/b2264555c87d8cbdd97bd1eb8b16387a/political-declaration-on-the-just-energy-transition-in-south-africa-data.pdf?download=1.

2“Joint Statement: International Just Energy Transition Partnership,” Government of the United Kingdom, November 2, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/joint-statement-international-just-energy-transition-partnership.

3“Joint Statement by the Government of the Republic of Indonesia (GOI) and the Governments of Japan, the United States of America, Canada, Denmark, the European Union, the Federal Republic of Germany, the French Republic, Norway, the Republic of Italy, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (together the “International Partners Group” or IPG),” Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany, December 15, 2022, https://www.bmz.de/resource/blob/239126/jetp-joint-statement-indonesia.pdf.

4“Political Declaration on Establishing the Just Energy Transition Partnership with Vietnam,” European Commission, December 13, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_22_7724.

5“Just Energy Transition Partnership with Senegal,” Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany, June 22, 2023, https://www.bmz.de/resource/blob/239128/jetp-political-declaration-senegal.pdf.

6Roli Srivastava and Julian Wettengel, “India, Donor Countries Give Up on Just Energy Transition Partnership – German Official,” Clean Energy Wire, November 20, 2024, https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/india-donor-countries-give-just-energy-transition-partnership-german-official.

7Jan Vanheukelom, “Two Years into South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership: How Real Is the Deal?,” ecdpm, November 27, 2023, https://ecdpm.org/work/two-years-south-africas-just-energy-transition-partnership-how-real-deal; and “Taking the JETP Path: Pushing for Change. Strategic Reflections from the JETP Learning and Knowledge Exchange Summit,” African Climate Foundation, September 2022, https://africanclimatefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/800723-ACF-JETP-Knowledge-exchange-06.pdf.

8“Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/putting-america-first-in-international-environmental-agreements/; and Tim Cocks, Francesco Guarascio, and Fransiska Nangoy, “Exclusive: US Withdraws from Plan to Help Major Global Polluters Move from Coal,” Reuters, March 6, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/us-withdrawing-plan-help-major-polluters-move-coal-sources-2025-03-05/.

9Béla Galgóczi, “Just Transition on the Ground: Challenges and Opportunities for Social Dialogue,” European Journal of Industrial Relations 26, no.4 (2020): 367–382, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0959680120951704; Patrick Schröder, “Promoting a Just Transition to an Inclusive Circular Economy,” Chatham House, April 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-04-01-inclusive-circular-economy-schroder.pdf; and Muhammed Patel, “Towards a Just Transition: A Review of Local and International Policy Debates,” Pretoria: Presidential Climate Commission, September 2021, https://pccommissionflo.imgix.net/uploads/images/PCC_Status-Quo-Report_Version-5_Low-2.pdf.

10“A Just Transition to a Low-Carbon and Climate Resilient Economy,” COSATU, August 2022, https://justtransitionforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Naledi_A-just-transition-to-a-climate-resilient-economy.pdf.

11Saliem Fakir, “South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership: A Novel Approach Transforming the International Landscape on Delivering NDC Financial Goals at Scale,” South African Journal of International Affairs 30, no. 2 (2023): 297–312, https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2023.2233006.

12Fakir, “South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership.”

13“Statement by H.E. President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa to the United Nations Secretary-General’s Climate Summit,” Department of International Relations and Cooperation, Republic of South Africa, September 23, 2019, https://dirco.gov.za/statement-by-h-e-president-cyril-ramaphosa-of-south-africa-to-the-united-nations-secretary-generals-climate-summit-23-september-2019/.

14Paul Bodnar et al., “How to Retire Early: Making Accelerated Coal Phaseout Feasible and Just,” Rocky Mountain Institute, 2020, https://rmi.org/insight/how-to-retire-early.

15“Carbon Tracker Initiative Country Profiles – Power and Utilities,” Republic of South Africa, last updated October 2023, https://countryprofiles.carbontracker.org/SouthAfricaCoal; and “Flexible Power Plant Operation to Enable High Renewable Energy Penetration,” Institute for Essential Services Reform, June 15, 2022, https://iesr.or.id/en/flexible-power-plant-operation-to-enable-high-renewable-energy-penetration/.

16“Project Profile: Climate Investment Funds, Accelerating Coal Transition Investment Program (CIF-ACT),” Government of Canada, accessed September 26, 2025, https://w05.international.gc.ca/projectbrowser-banqueprojets/project-projet/details/P010807001.

17“Just Energy Transition Partnership Indonesia: Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan 2023,” Government of Indonesia JETP Secretariat, November 21, 2023, 149, https://jetp-id.org/storage/official-jetp-cipp-2023-vshare_f_en-1700532655.pdf.

18“CIF Secures a Major New Contribution to the Clean Energy Transition,” Climate Investment Funds, October 27, 2022, https://www.cif.org/news/cif-secures-major-new-contribution-clean-energy-transition; and “International Climate Financing,” Government of Canada, accessed September 26, 2025, https://climate-change.canada.ca/finance/details.aspx?id=2668.

19“South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan,” Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, November 3, 2022, https://www.climatecommission.org.za/south-africas-jet-ip; “Just Energy Transition Implementation Plan 2023–2027,” Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, November 2023, https://www.stateofthenation.gov.za/assets/downloads/JET%20Implementation%20Plan%202023-2027.pdf; Government of Indonesia JETP Secretariat, “Just Energy Transition Partnership Indonesia”; and “Resource Mobilization Plan: Implementing Vietnam’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP),” Socialist Republic of Vietnam JETP Secretariat, November 2023, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-12/RMP_Viet%20Nam_Eng_%28Final%20to%20publication%29.pdf.

20“Joint Statement from the International Partners Group on the US Withdrawal from the Just Energy Transition Partnership in South Africa,” European Commission, March 19, 2025, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/news-your-voice/news/joint-statement-international-partners-group-us-withdrawal-just-energy-transition-partnership-south-2025-03-19_en.

21“Senegal Secures $2.7 Billion JETP Funding,” African Climate Foundation, May 16, 2025, https://africanclimatefoundation.org/blog/senegal-secures-2-7bn-jetp-funding/.

22“JET Grants Register,” Government of South Africa JETP Secretariat, accessed August 22, 2025, https://justenergytransition.co.za/jet-grants-register.

23Fakir, “South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership.”

24Grant Hauber, “Financing the JETP: Making Sense of the Package,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, December 22, 2023, https://ieefa.org/resources/financing-jetp-making-sense-packages.

25African Climate Foundation, “Senegal Secures $2.7 Billion JETP Funding.”

26Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, “South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP).”

27Julian Bocobza et al., “Vietnam Approves Power Development Plan for Cleaner Fuels,” White & Case, May 29, 2023. https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/vietnam-approves-power-development-plan-cleaner-fuels; and “Vietnam’s Eighth National Power Development Plan (PDP VIII),” PricewaterhouseCoopers, August 2023, https://www.pwc.com/vn/en/publications/2023/230803-pdp8-insights.pdf.

28Socialist Republic of Vietnam JETP Secretariat, “Resource Mobilization Plan: Implementing Vietnam’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP),” 44.

29Erica Hogan, “Why Debt Relief Matters to the Wealthy West,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 17, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/01/why-debt-relief-matters-to-the-wealthy-west?lang=en.

30“A Framework for a Just Transition in South Africa,” Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, June 2022, https://pccommissionflo.imgix.net/uploads/images/22_PAPER_Framework-for-a-Just-Transition_revised_242.pdf.

31Aljoscha Karg, Joyeeta Gupta, and Yang Chen, “Just Energy Transition Partnership: An Inclusive Climate Finance Approach?,” Energy Research & Social Science 125, (2025): 104103, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629625001847?fr=RR-9&ref=pdf_download&rr=95eae53c39cc4207

32“A Critical Appraisal of South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan,” Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, May 2023, https://climatecommission.imgix.net/uploads/images/PCC-analysis-and-recommenations-on-the-JET-IP-May-2023.pdf.

33Emily Tyler, Celeste Renaud, and Lonwabo Mgoduso, “Financial Support Needs for Mpumalanga’s Economic Transition: A Scoping Study,” Meridian Economics, March 9, 2021. https://meridianeconomics.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Financial-support-needs-for-MP-Just-Transition_final_2.pdf.

34Celeste Renaud, Emily Tyler, and Lonwabo Mgoduso, “The Just Transaction: Motivating Climate Finance Support for Accelerated Coal Phase Down,” Meridian Economics, May 2021, https://meridianeconomics.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/JTT-Motivating-climate-finance-for-accelerated-coal-phase-down.pdf.

35Gautam Jain and Ganis Bustami, “Realizing the Potential of Just Energy Transition Partnerships in the Current Geopolitical Environment,” Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, March 3, 2025, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/realizing-the-potential-of-just-energy-transition-partnerships-in-the-current-geopolitical-environment/.

36Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, “South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan,” 146–148; and Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, “Just Energy Transition Implementation Plan 2023–2027,” 16.

37David Pilling, “The Cost of Getting South Africa to Stop Using Coal,” Financial Times, November 2, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/3c64950c-2154-4757-bf25-d93c7850be8f; and Srivastava and Wettengel, “India, Donor Countries Give Up.”

38Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany, “Joint Statement by the Government of the Republic of Indonesia (GOI) and the Governments of Japan, the United States of America, Canada, Denmark, the European Union, the Federal Republic of Germany, the French Republic, Norway, the Republic of Italy, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.”

39“GHG Emissions of All World Countries,” European Commission, 2024, https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/report_2024.

40“Vietnam,” International Energy Agency, accessed August 22, 2025, https://www.iea.org/countries/viet-nam.

41“World Development Indicators,” World Bank, accessed July 28, 2025, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

42World Bank, “World Development Indicators.”

43“Just Energy Transition Partnerships: Toward a Collective Assessment,” United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, December 2023, https://cdn.unrisd.org/assets/library/briefs/pdf-files/2023/rpb-41-jetp.pdf.

44Shaun Jacobs, “Just Energy Transition a Foreign Concept – Mantashe,” Daily Investor, July 4, 2023, https://dailyinvestor.com/energy/22177/just-energy-transition-a-foreign-concept-mantashe/.

45Government of Indonesia JETP Secretariat,

“Just Energy Transition Partnership Indonesia,” 16–17.46Patrick Jowett, “Load Shedding Returns to South Africa,” PV Magazine, February 3, 2025, https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/02/03/load-shedding-returns-to-south-africa/.

47Chris Loewald, “South African Reserve Bank Occasional Bulletin of Economic Notes OBEN/23/01,” South African Reserve Bank, June 2023, https://www.resbank.co.za/content/dam/sarb/publications/occasional-bulletin-of-economic-notes/2023/reflections-on-load-shedding-and-potential-gdp-june-2023.pdf.

48Mary McColm, “Power-Hungry: The Influence of South Africa’s Electricity Crisis on National Elections.” Harvard International Review, March 26, 2025, https://hir.harvard.edu/power-hungry-the-influence-of-south-africas-electricity-crisis-on-national-elections/.

49Genesis Analytics, “Short-Term, Private Sector-Leg Employment Strategy for Mpumalanga,” Government of South Africa Presidential Climate Commission, August 2024, https://pccommissionflo.imgix.net/uploads/images/FINAL-Employment-Strat-Report-2608202437.pdf.

50“Primary Energy, Indonesia,” U.S. Energy Information Agency, accessed August 22, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/total-energy-consumption?pd=44&p=000000001&u=2&f=A&v=mapbubble&a=-&i=none&vo=value&t=C&g=none&l=249--104&s=315532800000&e=1672531200000.

51“Electricity Data Explorer,” Ember, accessed August 22, 2025, https://ember-energy.org/data/electricity-data-explorer/?entity=Indonesia.

52Jobit Parapat and Katherine Hasan, “Emerging Captive Coal Power: Dark Clouds on Indonesia’s Clean Energy Horizon,” Global Energy Monitor, September 2023, https://globalenergymonitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/CREA_GEM_Indonesia-Captive_2023.pdf; and Dody Setiawan, “Captive Coal Expansion Plans Could Undermine Indonesia’s Climate Goals,” Ember, February 20, 2025, https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/captive-coal-expansion-plan-could-undermine-indonesias-climate-goals/.

53“Why Indonesia Needs Datacenters for an AI-Powered Future,” Microsoft, January 22, 2025, https://news.microsoft.com/source/asia/2025/01/22/why-indonesia-needs-datacenters-for-an-ai-powered-future/; and Mutya Yustika, “Unlocking Indonesia’s Renewable Energy Investment Potential,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, July 23, 2024, https://ieefa.org/resources/unlocking-indonesias-renewable-energy-investment-potential.

54Ernst Kuneman et al., “Electricity Market Designs in Southeast Asia,” Clean, Affordable, and Secure Energy for Southeast Asia, 2024, https://caseforsea.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/EN-Electricity-Market-Designs-in-Southeast-Asia.pdf.

55Hans Nicholas Jong and Jeff Hutton, “As Indonesia, US Back Away from Climate Goals, Hopes Fade to Retire Coal Plants Early,” Mongabay, February 20, 2025, https://news.mongabay.com/2025/02/as-indonesia-us-back-away-from-climate-goals-hopes-fade-to-retire-coal-plants-early/.

56Mirzat Ullah et al., “The Connection Between Disaggregate Energy Use and Export Sophistication: New Insights from OECD with Robust Panel Estimations,” Energy 306 (2024): 132282, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360544224020565.

57Zainab Usman, “How African Countries Can Harness the Global Policy Reframe from Energy Transition to Energy Security,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 21, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/05/africa-energy-security-transition?lang=en.

58Nick Simpson, Archie Gilmour, and Michael Jacobs, “Taking Stock of Just Energy Transition Partnerships,” Overseas Development Institute, December 2, 2023, https://odi.org/en/publications/taking-stock-of-just-energy-transition-partnerships/.

59Dharna Noor, “‘Project 2025’: Plan to Dismantle US Climate Policy for Next Republican President,” Guardian, July 27, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jul/27/project-2025-dismantle-us-climate-policy-next-republican-president; and Robinson Meyer and Jesse D. Jenkins, “Climate Policy in America: Where Do We Go From Here?” Heatmap, July 16, 2025, https://heatmap.news/podcast/shift-key-s2-e48-obbba-debrief.

60Karin Rives, “With JP Morgan Gone, All Major U.S. Banks Have Now Left Global Climate Alliance,” S&P Global, January 7, 2025, https://www.spglobal.com/market-intelligence/en/news-insights/articles/2025/1/with-jpmorgan-gone-all-major-us-banks-have-now-left-global-climate-alliance-85961423; and “Why Big Banks Are Leaving the Net Zero Banking Alliance,” Asuene, July 15, 2025, https://asuene.com/us/blog/why-big-banks-are-leaving-the-net-zero-banking-alliance.

61“Presidential Recommendations on Discretionary Funding Levels for Fiscal Year 2026,” Executive Office of the President of the United States, Office of Management and Budget, May 2, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Fiscal-Year-2026-Discretionary-Budget-Request.pdf.

62“Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent Remarks Before the Institute of International Finance,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, April 23, 2025, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0094.

63“Our Updated Sustainable Finance Targets,” Standard Bank, April 7, 2025, https://www.standardbank.com/sbg/standard-bank-group/newsroom/news-and-insights/our-updated-sustainable-finance-targets.

64Erica Yokoyama, “Japan, Germany Step Up on Indonesia Climate Deal as US Exits,” Bloomberg, March 7, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-07/japan-and-germany-partner-on-indonesia-climate-deal-as-us-exits?embedded-checkout=true.

65Nicholas R. Micinski, “Why the ‘Finance COP’ in Baku Missed the Mark,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 28, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/01/cop29-climate-finance-scale-logistics?lang=en; and David G. Victor, “COP28 and the Ghosts of Copenhagen,” Brookings Institution, December 7, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/cop28-and-the-ghosts-of-copenhagen/.

66“South African Renewable Energy Masterplan,” Government of South Africa Department of Electricity and Energy, April 2, 2025, https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202506/south-african-renewable-energy-masterplan.pdf.

67“About the JET Funding Platform,” Government of South Africa JETP Secretariat, 2025, https://justenergytransition.co.za/jet-funding-platform.

68Sunday Jerome Salami, “Attracting Climate Finance to Africa Through the Development of Bankable Project Pipelines,” United Nations Development Program Sustainable Finance Hub, November 11, 2024, https://sdgfinance.undp.org/news-events/attracting-climate-finance-africa-through-development-bankable-project-pipelines.

69Vijaya Ramachandran, “The World Bank’s ‘All of the Above’ Approach to Energy in Poor Countries Is a Welcome Change,” Center on Global Development, April 18, 2025, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/world-banks-all-above-approach-energy-poor-countries-welcome-change.

70“US Energy Secretary Says Washington ‘Wants to Partner with African Countries,’” Voice of America, March 7, 2025, https://www.voaafrica.com/a/us-energy-secretary-says-washington-wants-to-partner-with-african-countries-/8002752.html.

71Executive Office of the President of the United States, “Presidential Recommendations.””

72David Timmons, Jonathan M. Harris, and Brian Roach, “The Economics of Renewable Energy,” Boston University Global Development Policy Center, 2024, https://www.bu.edu/eci/files/2024/03/renewable-energy-econ-module-final.pdf; and Laura Cozzi et al., “Clean Energy is Boosting Economic Growth,” International Energy Agency, April 18, 2024, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/clean-energy-is-boosting-economic-growth.

73“Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism,” European Commission, 2025, https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en.