George Perkovich

Source: Getty

How to Assess Nuclear ‘Threats’ in the Twenty-First Century

The less precise our nuclear discourse, the more fear nuclear manipulators can elicit.

The Nautilus Institute and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace thank the Carnegie Corporation of New York for its support of this project and its ongoing support of public-interest work to prevent nuclear conflict.

Introduction

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 and then faced a devastating loss around Kherson that September into October, the salience of nuclear risk rose to a level unknown since the Cuban Missile Crisis sixty years earlier.1 Excellent researchers at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs produced a 257-page index of Russian nuclear threat-related statements and international responses through June 2023.2 The United States’ Voice of America asserted that Russia had made 135 ‘nuclear threats’ between 24 February 2022 and 17 December 2024.3

The menacing nuclear rhetoric is new and bewildering for people who came of age after the Cold War. Some commentators have bemoaned that nuclear threats have deterred the West from helping Ukraine ‘win’ the war—they suggest Russian leaders have been ‘bluffing’.4 Others have worried that inadequate caution could blunder the antagonists into nuclear war.5 A not dissimilar confusion occurred with the May 2025 India-Pakistan conflict. President Donald Trump, after the ceasefire was announced, said, ‘We stopped a nuclear conflict, I think it could have been a bad nuclear war’.6 But new Carnegie papers by outstanding Pakistan and India analysts conclude that neither side made nor perceived the other to make a nuclear threat.7

Presumably, humankind would applaud leaders who recognized when a reported nuclear ‘threat’ was hollow and then refused to do what the issuer wanted. Conversely, when an adversary leader was really willing to use nuclear weapons to avert a big loss, presumably current citizens and future historians would assess whether the value of the territory being fought over was worth the damage and costs of nuclear war. The challenge, or imperative, is to judge correctly in real time whether and when a decisionmaker is really on the verge of ordering nuclear detonations.

Careful analysis shows that Russian leaders between February 2022 and the end of 2024 did not make 135 ‘nuclear threats’ that deserved to be taken seriously, contrary to what Voice of America and other media might have suggested. Most so-called nuclear threats were frightening allusions to Russia’s nuclear strength and the horror of nuclear war, or symbolic gestures unaccompanied by changes in the operational status of nuclear forces. But, at least once, in late September, through to early October 2022, public and secretly collected evidence indicated that Russian military leaders were setting the stage for possibly detonating non-strategic nuclear weapons to stop Ukrainian advances.

In cases like the Ukraine war, and in militarized crises that may arise between India and Pakistan and in northeast Asia, it behoves policymakers, media, scholars, and concerned citizens to decode and assess how leaders manipulate fear of nuclear war to pursue their aims. Usually, the aim is to increase fear that nuclear weapons will be used. Sometimes, however, leaders seek to win political support by relieving fear of nuclear war. In sum, the objectives of nuclear manipulations are to:

- Deter or compel adversaries;

- Reassure allies, home populations, and, on occasion, adversaries;

- Gain political support, at home and in international society; and/or

- Decrease competitors’ political support, at home and in international society.

This paper and other publications of this project aim to help targets of nuclear manipulations analyse and talk about them so that they can better decide when and how to respond.8 Assessing nuclear manipulations—threats or signals—is a subjective task that will not yield certain, readily codable results, for reasons explained below. But a more nuanced framework for such assessments can help avoid self-defeating under- or overestimations of so-called threats.

Discourse that too readily labels leaders’ utterances or gestures as threats can inflate fear and weaken national or alliance resolve to defend against aggression. When threats are inflated and the feared actions do not transpire, people may become inured and stop preparing adequately to respond when the moment is truly dire. Conversely, dismissing, without careful study, menacing nuclear rhetoric and gestures as a bluff may expose states and alliances to grave dangers. More careful analysis can prevent a nuclear bully from getting a cheap win or save a brave defender from a fight it will lose catastrophically.

The Challenges of Ambiguity

Clear and accurate assessments of adversary nuclear intentions are extremely difficult to make because governments tend to cloak their nuclear words and deeds in ambiguity.

For example, in the first armed clashes directly involving nuclear-weapon states—between the Soviet Union and China along their disputed riverine boundary on 2 and 15 March 1969—Soviet leaders raised the alert status of the Strategic Rocket Forces in the Far East for several days. Changes in force posture are undertaken for one or more reasons: to prepare for intended launch; to gesture the gravity of a situation in order to deter or compel the adversary; and/or to make forces more survivable in anticipation of enemy preemptive attack. As the Sino-Soviet crisis continued for months, in September 1969 a Soviet writer with known KGB-connections published an article in the London Evening News declaring there was not ‘a shadow of a doubt that Russian nuclear installations stand aimed at Chinese nuclear facilities’, and ‘the world would only learn about [a Soviet decision to strike] afterwards’. The author, Victor Louis, closed, however, by writing there were ‘no noticeable preparations for war’ in Moscow.9 This hinted that the Soviet alert was more diplomatic compellence than preparation for intended use of nuclear weapons. As Michael Gerson concluded in his admirable study of this conflict, ‘There is no available evidence . . . that Moscow ever seriously contemplated launching a nuclear strike. Rather, it appears that the nuclear threats, including the probes to Washington and elsewhere, were part of Moscow’s coercive diplomacy strategy designed to pressure Beijing into negotiations’.10

Ambiguity clouds nuclear manipulations for many reasons. The most authoritative leaders may not be clear in their own minds about what they intend to do. Top leaders may differ in opinion over what their government should do and want to test various audiences’ reactions to possible moves. (Audiences bring their own uncertainty and confusion, too, as discussed below.) Leaders may feel that ambiguity maximizes adversaries’ fear and retains their own flexibility to act.

These motivations may combine with legal considerations: according to the judge advocate general of the United States Strategic Command (the entity responsible for U.S. nuclear war planning), ‘U.S. policy has always been to avoid making a direct threat to use nuclear weapons . . . because of the controversy associated with nuclear weapons’.11 Instead, the lawyer wrote, ‘The U.S. traditional response to the possibility of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) has been to state that we will “consider all options available to us in response to an attack using WMD”’. Beyond this lawyer’s perspective, ambiguous formulations serve strategic and political interests in avoiding commitment traps and/or loss of reputation and deterrent credibility when a leader does not execute a threat.

Ambiguity grows with the number of audiences being manipulated. In many crises or conflicts, each leadership is trying to manipulate adversary leaders and publics; allies; their own population; powerful countries not directly involved in the conflict; and international society. Such manifold manipulations certainly occurred in the 1969 Sino-Soviet episode quoted above, in all India-Pakistan crises since 1998, and in the Ukraine war. Indeed, by definition, when a conflict involves the United States (along with others) defending a friend threatened by a nuclear-armed opponent, nuclear manipulations will target the attacked state, its supporters, and potential joiners in sanctions against the aggressor.

Underlying it All: Fear of Nuclear War

The use of the term threat to shorthand a wide range of rhetoric and behaviour involving nuclear weapons is problematic. Threat suggests a linear dynamic: actor A will hurt actor B, if B does not accede to A’s demand. But intentions, capabilities, and triggering circumstances for nuclear war are rarely crystal clear for leaders let alone for their potential targets. This is indicated by the fact that since 1945 no one has detonated nuclear weapons against an adversary, despite many reported ‘threats’ to do so. Rather than clear nuclear threats, adversaries tend to issue what could more accurately be called veiled or indirect threats. But less accurate discussions, including in media, tend to drop the adjectives and ‘threat’ remains—as in the report that Russia issued 135 ‘nuclear threats’ between February 2022 and the end of December 2024. This is one reason why I suggest a more nuanced framework and vocabulary, as elaborated below, where nuclear allusion is used to describe invocations of nuclear danger that do not go so far as declaring that state A will use nuclear weapons against B, if B does not comply.12

Thomas Schelling famously summarized nuclear strategy as a manipulation of risk13: manipulations are the things that leaders say or do with regard to nuclear weapons to shape how target audiences perceive the risks of the relevant situation and their options for raising or lowering such risks in response.14 I would amend this insight to reflect unique qualities of nuclear weapons. More than a rational appraisal of risk (the estimated probability of nuclear use multiplied by the estimated consequences), what is being manipulated is the fear of the horror that nuclear war would bring. Such fear may be exploitable in ways not captured by rational-actor risk calculations of probability-times-consequence of nuclear escalation. Put differently, people fear (for good reason) even getting close to what Schelling in his 2005 Nobel Peace Prize lecture called the ‘slippery slope’ of nuclear first use which is the basis of deterrence.15

The slippery slope toward nuclear war makes any serious crisis among nuclear-armed adversaries alarming. This tempts some actors (but not all) to invoke nuclear weapons to turn around an unwelcome situation. The role of government and think tank analysts, scholars, and serious journalists is to carefully assess the level of danger indicated by what is being said and done, and the surrounding circumstances.

Manipulations Run in Multiple Directions: Threatening, Counteracting, Fear-Relieving

Manipulations of nuclear fear are not unidirectional. For each contestant’s bid there is often a counter-manipulation by the opponent(s). Most allusions or threats pointing to possible nuclear use are met by counter-manipulations: warnings of some sort of military reprisal and/or political economic sanction, or in some cases studied silence. For example, two days after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, warning that the ‘consequences’ of resisting Russia ‘will be such as you have never seen in your entire history’, French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian countered ‘that Vladimir Putin must also understand that the Atlantic alliance is a nuclear alliance. That is all I will say about this’.16 Whether they are categorized as offensive or defensive, competing states will manipulate and counter-manipulate nuclear fears in an attempt to achieve bargaining leverage in a crisis or conflict.

Nuclear manipulations are not always hostile or threatening. Words and deeds that relieve the fear of nuclear war can serve contestants’ interests.

As noted above, nuclear manipulations are not always hostile or threatening. Words and deeds that relieve the fear of nuclear war can serve contestants’ interests. When a state reduces the alert levels of its nuclear forces, or offers to negotiate arms control measures and sanctions relief, for example, it seeks to win audiences’ favour by relieving fear. Downplaying an adversary’s or one’s own threatening words or gestures is another form of relieving manipulation. (Offering relief can be seen as risky, too, however. Leaders may worry that their own population or the adversary will think they are weak if they offer a reciprocal way out of a crisis or conflict.)17

When Pakistan tested several nuclear-capable missiles during a May 2002 crisis with India, the Indian foreign ministry de-escalated the situation—and took the high ground—by declaring ‘India is not particularly impressed by these missile antics clearly targeted at the domestic audience in Pakistan’.18 After the world reacted harshly to Putin’s perceived 21 September 2022 nuclear threat, one month later he declared ‘we have never said anything proactively about Russia potentially using nuclear weapons. All we did was hint in response to statements made by Western leaders’.19 NATO leaders also had interests in downplaying Russian manipulations in order to reassure European populations that it was not too dangerous to support Ukraine militarily.

Many Attempted Manipulations Do Not Succeed

It is often difficult to assess whether manipulations have succeeded—whether adversaries have been deterred or compelled by an opponent’s words and deeds, or whether allies have been reassured, and global citizens won over or turned off by a leader’s attempt to raise or reduce fear of nuclear war.20 Governments proclaim that their policies and arsenals deter adversaries or reassure allies, but it is very difficult to measure how and when these policies and arsenals achieve the desired result.21

The perspectives of senders and recipients are important.22 Outcomes of crises or conflicts will depend on the words and deeds of all antagonists, not only the initiator of nuclear manipulations. But targets of nuclear manipulations may interpret them differently than the sender intended. Or, targets may not perceive them at all.

In the 1986–87 India-Pakistan ‘Brasstacks’ crisis, a leader of Pakistan’s nuclear program told a visiting Indian journalist that Pakistan could test an atomic bomb and ‘shall use the bomb if our existence is threatened’—an allusory warning for New Delhi. However, the enterprising journalist spent several weeks seeking a higher bid for publication of this interview, long delaying the intended warning. In 1969, then president Richard Nixon and national security advisor Henry Kissinger orchestrated the infamous ‘Madman Alert’ of U.S. nuclear forces to compel Soviet leaders to pressure Vietnamese leaders to make concessions in Paris talks with South Vietnam and the United States. Neither the Soviet nor Vietnamese governments appeared affected by the U.S. gesture.23

It is much more difficult to code responses to manipulations of nuclear fear than it is to refine how we categorize and understand manipulations themselves. The definitions of manipulations offered here are from the perspective of senders. I do not assess how and when allusions or gestures toward nuclear use have deterred, or are likely to deter, targeted governments, or have reassured the citizens of the state whose leader is making the allusion or gesture.24 The premise here is that we can gain useful insights from studying the intentions and forms of nuclear manipulations without examining in depth how they were perceived and acted upon. More debatably, regardless how targeted audiences perceived and responded to manipulations, we can assess their gravity, as sketched in the next section below.

Defining More Useful Terms

Setting the Context of Imminence

An alternate vocabulary could give officials, journalists, scholars, and citizens a better framework for interpreting how contestants in crises or conflicts are trying to manipulate audiences. If the aim is to avert nuclear war without thereby emboldening future aggressors, how should we think and talk about all this? The objective should be to avoid ‘the boy who cried wolf’ hazard, on one hand, and the Pearl Harbor or Operation Barbarossa hazards on the other.25 If everything is a threat and nothing happens, people become ill-prepared to notice and act when the danger is real. Conversely, if it is assumed that one wouldn’t dare attack, then people may become less likely to discern when adversaries have become desperate enough to take the risk. And, if one’s own state or alliance may need to make a genuine threat against an adversary, it’s credibility will be higher if the term (threat) has not been devalued by applying it to lesser manipulations.

If everything is a threat and nothing happens, people become ill-prepared to notice and act when the danger is real.

We will start with frightening manipulations (as distinct from fear-relieving ones). First, we need to distinguish the context; the topic here centres on crises and conflict, not more general competitions among nuclear-armed states.

Each nuclear-armed state has standard operating procedures for its nuclear forces in non-crisis peacetime. These procedures and capacities provide a background general deterrent of potential adversaries.26 Anyone contemplating major aggression against a nuclear-armed state needs to consider that they could trigger a nuclear response—if not immediately, then after a series actions and reactions.

General deterrence is also meant to reassure allied governments and populations that because they are members of a nuclear-armed alliance no one will dare commit large-scale aggression against them. This sharing of a nuclear umbrella can help reduce pressures for states to acquire nuclear weapons of their own. Yet, these salutary effects of general deterrence can have unintended negative consequences as conveyed by the stability-instability paradox: nuclear deterrence of large-scale war may encourage competitors to undertake lower-intensity aggression in the belief that the opponent will not escalate violence in response, for fear of inviting nuclear exchanges.27

Other effects of basic peacetime nuclear postures include the shaping of adversaries’ nuclear force structures and postures (possibly arms racing) and political-economic-environmental effects of nuclear arsenal production and testing.

More rarely, states may manipulate their potential (latent) possession of nuclear weapons to deter or compel competitors and/or reassure their own populations. Hashemi Rafsanjani, who had been Iran’s president from 1989 to 1997, did this at a conference in Tehran in 2005. Standing on an auditorium stage, he declared that Iran did not seek to build nuclear weapons but instead to master the nuclear fuel-cycle. With this capability, he said, ‘all our neighbors will draw the proper conclusion’.28

As a physical matter, general deterrent forces like those of Russia and the United States, with submarines and land-based missiles operationally deployed, could be launched within minutes without preceding threatening statements or indications. The risk of technical failure or warning-system errors by machines or humans makes such operationally deployed arsenals inherently dangerous.29 But, it is more likely that the transition from background deterrence toward an imminent threat of nuclear use would involve purposeful changes in the physical disposition of delivery systems and warheads—a raising of alert levels to the highest level—and some demand that must be met to avoid nuclear consequences. The pace of conflictual events likely would be accelerating and the slippery slope steepening.

This essay focuses on leaders’ intentional manipulations of nuclear risk in crises or conflicts where the threatened or alluded-to nuclear use might be imminent. It does not address the challenges of accidental nuclear use or nuclear use by suicidal non-state actors who somehow took control of nuclear weapons.

I use the term nuclear manipulation as shorthand to describe changes in speech and action in the lead-up to or during crises or conflicts when authorities in one state foreground nuclear weapons in order to deter, compel, or reassure targeted audiences.30 International crises and conflicts involving nuclear-armed states (directly or via alliance or partnership) are scenarios of ‘immediate deterrence’, as Patrick Morgan coined it. The transition from general to immediate deterrence creates and reflects the impetus to manipulate targets without actually slipping over the edge of a waterfall and plunging into nuclear war. Manipulations and counter-manipulations drive the crisis or conflict up or down the escalation ladder depending on the intentions, perceptions, and decisions of the actors.

Assessing Intentions

This paper focuses primarily on four distinct types of frightening manipulations which are categorized as follows in order of their frequency: words that are 1) allusions or 2) expressed threats, and actions that are 3) gestures or 4) preparations for imminent use of nuclear weapons. All of these manipulations may occur on a spectrum of less-to-more ominous. The combination of words and actions that nuclear-armed leaders project, and the circumstances surrounding them, leads to what I call the assessed threat. As discussed below, assessment shows that the number of credible nuclear threats since 1962 has been much lower than leaders’ allusions and gestures suggest.

Actors’ intentions are largely what drives movement along the spectrum. But, to repeat, leaders may not clearly know what they intend if and when their initial aims are thwarted—that is, they may not know or share how hard they are willing to push through resistance.

Personalities matter too. Some leaders tend to play their cards very close to the vest and be understated. Barack Obama, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Manmohan Singh come immediately to mind. Some, like Nikita Khrushchev and Donald Trump, are impulsive and blustery, not careful about seeming to make threats. Vladimir Putin often hints calmly at menacing possibilities while lawyerly preserving a basis to deny having made threats. If varying personalities affect the frequency and characteristics of leaders’ nuclear rhetoric and gestures, it is difficult to say whether and how personalities have affected the gravity of actual nuclear threats. After all, no leader has ever detonated a nuclear weapon in a conflict where an opposing side could respond in kind.

Specifying leaders’ intentions is perhaps the most difficult challenge for intelligence agencies and other observers to meet. For all these reasons, most statements cannot be objectively assessed and coded as threat or allusion in ways that would be indisputable in politics or statistical analysis.31

Assessment Questions

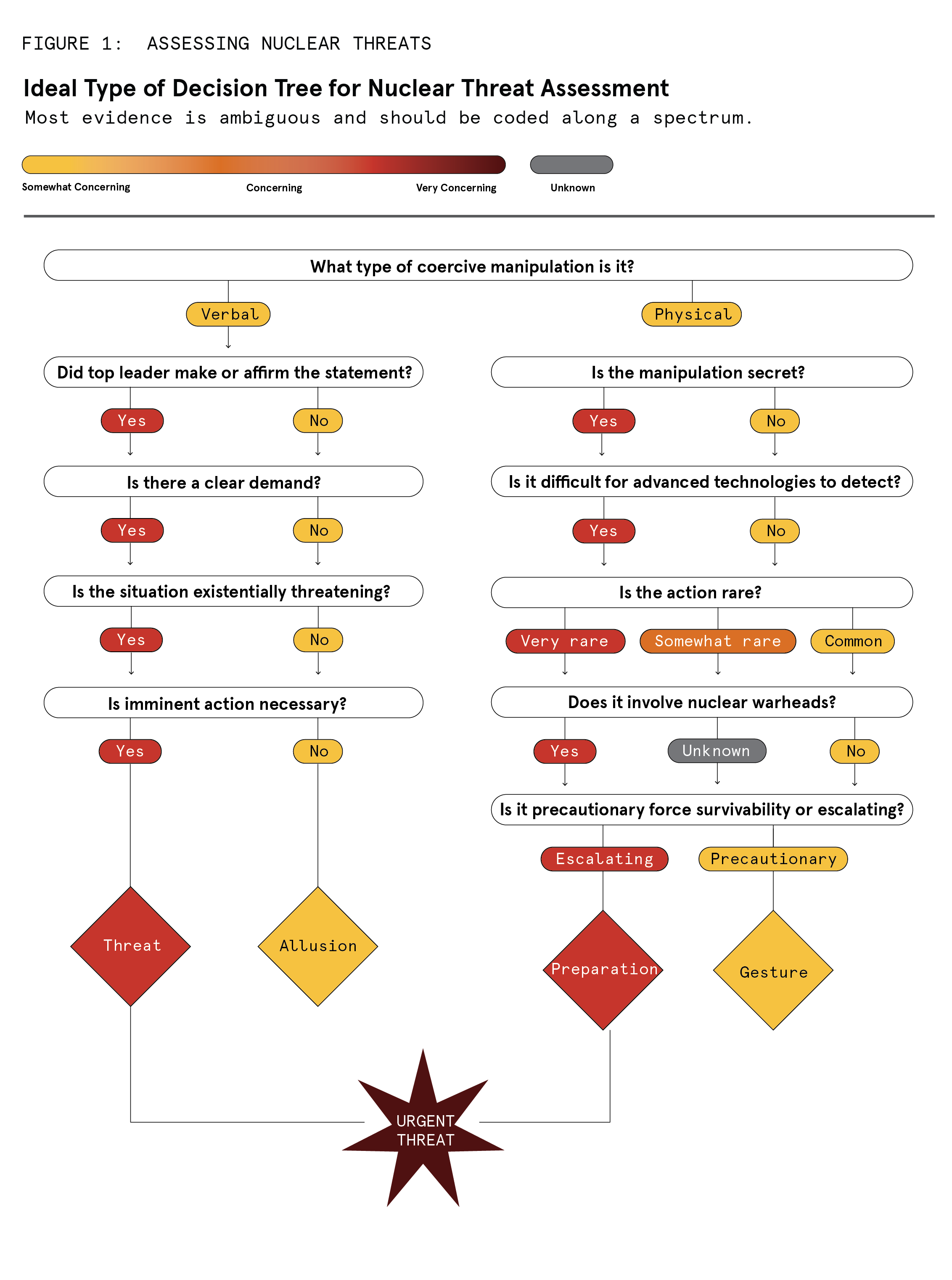

I suggest four questions for assessing the gravity of verbal manipulations:

- Did the leader with nuclear launch authority make or associate themselves with the statement?

- Is there a clear demand made of adversary targets?

- Do the losses experienced by the state in question meet criteria for nuclear use as defined by its doctrine or leaders?

- Is imminent action necessary to relieve the perceived threat to the state/leader, and/or to preempt an adversary from initiating nuclear use against the state or its allies?

The more specifically that the answers to these questions are ‘yes’, the graver the verbal manipulations should be judged. Because available information and/or the reality of a situation is unlikely to allow binary ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers, colour-coding could convey assessors’ assessments. A scale of shading represents from white (unquestioned ‘no’) to a yellow-to-red spectrum, with dark red representing the most dangerous assessment. Gray can represent lack of adequate information on which to make an assessment.

I suggest five questions for assessing the gravity of physical manipulations:

- Is the manipulation secret (unannounced)?

- Is it exceptionally difficult for advanced technologies to detect?

- Is the action rare?

- Does it involve nuclear weapons?

- Is it more consistent with nuclear attack than with ensuring survivability of forces and personnel?

If the answers to these questions are ‘yes’, the manipulation would be assessed as very grave. Again, colour-coding could convey assessments. Figure 1 shows the ideal logical flow required to assess a given nuclear threat, identifying the many necessary conditions that must be met to result in an ‘urgent’ threat. The comparison highlights that rigorous assessment of nuclear threats can distinguish serious, urgent nuclear threats from those that do not pose an immediate threat of nuclear attack.

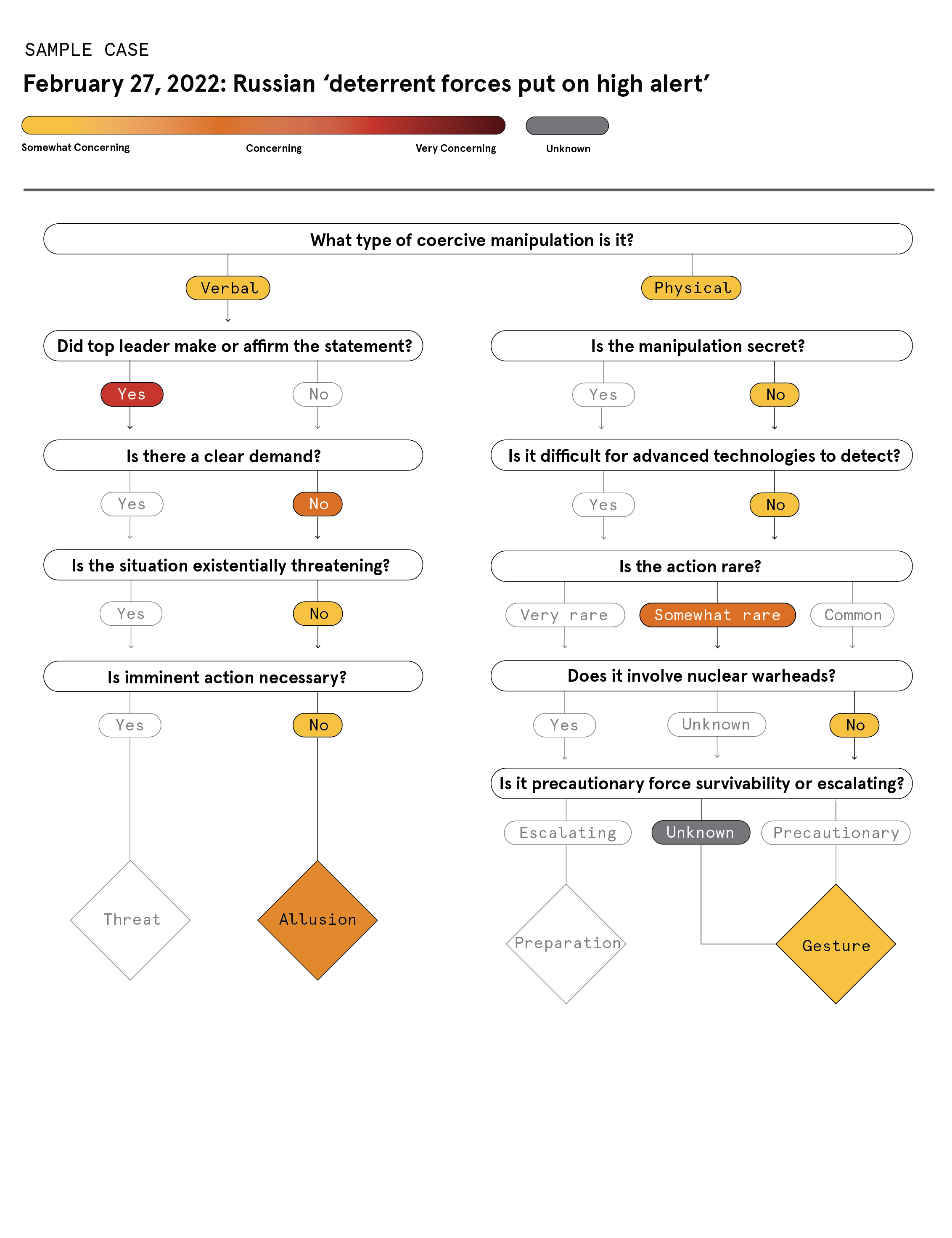

The first case study applies this framework to the 27 February 2022 incident involving Russian nuclear forces. The framework assesses it to be an example of an allusory nuclear threat accompanied by a gesture involving nuclear forces—but not an urgent threat.

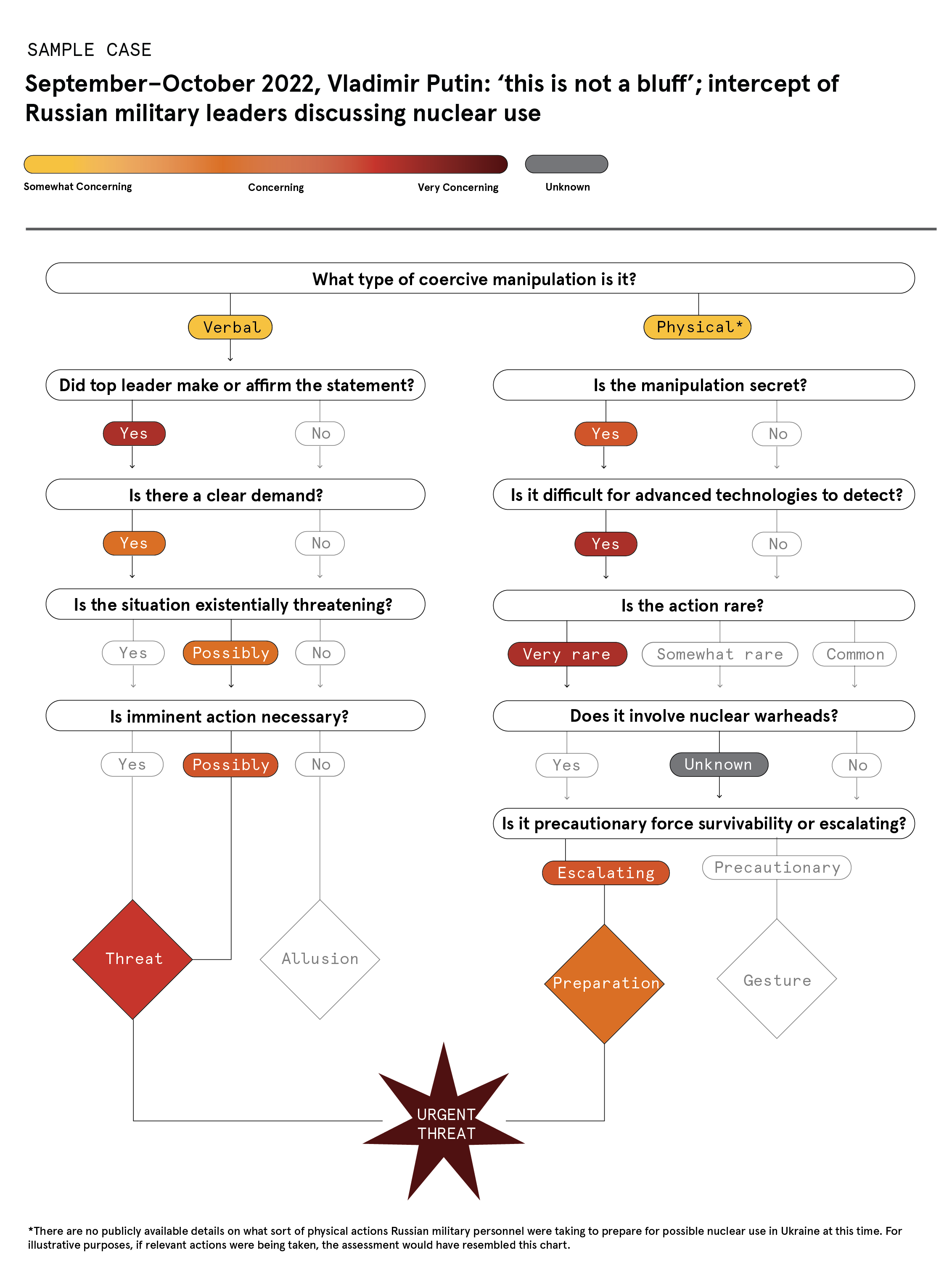

The second case study applies this framework to Putin’s nuclear threats in September-October 2022 and concludes that indeed, these threats were urgent.

Overall assessments of the gravity of a given situation would merge assessments of verbal and physical manipulations. The absence of nuclear war since 1945 and the rarity of serious nuclear threats since 1962 suggest that in a crisis or conflict involving nuclear-armed opponents, manipulative words and deeds will extremely rarely point clearly in one direction toward nuclear use. Most likely, some key indicators will be ambiguous, absent, and/or undetectable. The inherent, exceptional danger of nuclear war will make any crisis among nuclear-armed opponents feel serious, even if careful analysis identifies reasons to doubt imminent nuclear use.

The following four terms are used to shorthand definitions of verbal and physical manipulations.

Allusion: A reference to one’s possession of nuclear weapons and the damage they could do which does not convey a specific or imminent threat to initiate their use.32 The manipulator here has not decided whether they would use nuclear weapons nor ordered their nuclear forces to advance preparation for use. The lower the national authority of the person speaking, and the farther from an armed conflict, the more likely the manipulation is noise rather than serious threat. (This is akin to ‘taking the offensive through firing empty canons’, as Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao once described his effort to ‘scare’ Soviet leader Khruschev ‘for a moment’.33)

More recent examples of allusion include when Putin, in a joint press briefing with French President Emmanuel Macron on 8 February 2022 (sixteen days before the Russian invasion), denied any plans to invade but expressed concern about Ukraine joining NATO and then trying to take Crimea back. ‘Of course’, he said, ‘NATO’s united potential and that of Russia are incomparable. We understand that, but we also understand that Russia is one of the world’s leading nuclear powers, and is superior to many’.34

Another example of allusion was when Trump tweeted to North Korean leader Kim Jung Un in January 2018, ‘I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!’35 Trump’s taunt that his nuclear button works, unlike Kim’s button, could have unintentionally indicated U.S. capabilities to covertly cause North Korean missile launches to fail.36 Trump also could have intended North Korean leaders to infer a U.S. capability to make Kim’s button fail and thereby lose confidence in their capacity to deter or coerce the United States. Or Trump’s utterance was meaningless. This range of possibilities suggests that if and when a leader seeks to make a serious threat, he or she should speak clearly. Otherwise, vague or ambiguous utterances can prompt dangerous overreaction just as easily as they prompt desired accommodation.

Gesture: An action related to the posture of nuclear forces which the state wants adversaries and potential third parties to detect.37 To be noticeable such gestures often depart from routine practices regarding the posture of nuclear forces. Such action could be hollow, meaning it is not an actual preparation to enact a threat.38

The word signal is often used to describe such actions, but, following Robert Jervis, a signal is also often used to indicate any message that a state projects to influence how others perceive it.39 To avoid confusion, we use the term manipulation to convey the general signalling of nuclear risk, and gesture to convey the physical manipulation of capabilities which audiences are meant to detect.

For example, on 19 February 2022—days before the invasion of Ukraine—Putin and Belarussian President Aleksandr Lukashenko attended an exercise of Russian strategic forces. Exercises are not necessarily manipulative gestures. But this one was videorecorded from many camera angles and shown widely through European media, indicating it was primarily meant to manipulate European opinion.40 More subtly, in March 2022, weeks after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Macron ordered two additional nuclear-armed submarines to sea, to join the one already routinely deployed. This unprecedented move to have three of France’s four nuclear-armed submarines at sea was not announced, but Macron intended for it to be detected by Russian officials.41 This gesture was not an actual preparation or threat to launch nuclear weapons as French officials made no threatening statement; neither France nor a NATO ally had been attacked; Russia had no interest in attacking France or its vital interests and displayed no preparation to do so; and Macron at the time was positioning himself to be a diplomatic intermediary with Putin. It was apparently a gesture of French resolve to counter Putin’s manipulations of nuclear fear.

Preparation: Steps undertaken by a state to prepare for the deployment and potential imminent use of nuclear weapons.

When a state detects another actor taking the extremely rare steps necessary to target and launch nuclear warheads, it would prudently judge the nuclear threat to be credible and urgent. (Conversely, verbal allusions or even threats of nuclear use that are not accompanied by physical preparations are less urgent, though still alarming.)

Ambiguity of actions and, often, accompanying speech make it very difficult to assess whether detected actions are: 1) true preparations to imminently conduct nuclear attack; 2) mere gestures meant to deter or compel the opponent; or 3) defensive measures to protect one side’s nuclear capabilities from possible preemptive strike by the other (and therefore intended to be stabilizing and avoidant of nuclear war rather than aggressive). Again, historically, most actions that could have been perceived as preparations for nuclear use were in fact manipulative gestures and/or defensive asset-protection measures.42

During the Ukraine war it has been very telling that in nearly all instances where media have reported Russian nuclear threats, officials from the United States, United Kingdom, France, and NATO have announced that they have detected no preparations to use nuclear weapons.43 In the one episode (September into October 2022) when officials assessed a credible threat of Russian nuclear use, that assessment was based on so-called exquisite intelligence, the details of which have not been described.44 I have heard vague allusions that this intelligence included indications of some activity possibly to prepare non-strategic nuclear weapons for use.

More historically, former secretary of state and national security advisor Henry Kissinger explained in 1985 that the shift of global U.S. military forces’ readiness in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war from defence condition (DEFCON) 4 to 3 was not preparation for possibly using nuclear weapons. Kissinger was often duplicitous, and in 1973 he and Nixon were clearly gesturing with nuclear weapons. Yet, Kissinger’s 1985 telling seems to be a more accurate reflection of U.S. nuclear intentions, and closer to what Moscow perceived:

We were attempting to convey to the Soviets that we would oppose their move into Egypt. And we wanted to take certain actions that they would pick up through their intelligence. . . . It was a general alert that also alerted some nuclear forces. . . . Some people on leave get called back to their bases and some more bombers are put on alert and similar measures. . . . We were far from a decision to go to nuclear war.45

Kissinger’s famous book Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy (1957) fixated on his perceived need to make nuclear threats credible as a tool of statecraft. Yet, he declared in the 1985 interview that the Nixon administration was ‘Never even close [to nuclear war]’. The same would or could be said about every U.S. administration since then.46

If nuclear use were actually intended, nuclear weaponeers and decisionmakers would probably try to conceal preparations to make it harder for adversaries to preempt or otherwise defend against an attack. Preparations could include a situation like Russian personnel taking nuclear warheads from secure storage in Belarus and mounting them on Iskander missiles and moving the missiles (with deception) to possible launch points to avoid their preemptive destruction. Or U.S. personnel taking nuclear-armed AGM-86B air-launched cruise missiles and loading them onto B-52 bombers and keeping them on airborne alert for possible use against targets on the periphery of Russia.

Expressed threat: Again, the subject here is intentional threat in a crisis or conflict, not the inherent threat or danger that nuclear weapons could be launched and detonated through technical malfunction, accident, or inadvertence. An intentional threat entails an official statement, verbal or written, backed by preparation and/or gestures that altogether convey that nuclear weapons may be used imminently if adversaries do not refrain from certain actions (deterrence) or change behaviour (compellence).

Expressed threats may or may not be credible, however. For an expressed nuclear threat to be assessed as credible it must be attributable to the leader(s) empowered to authorize nuclear use and would combine an explicit demand with physical preparations to imminently release nuclear weapons, and circumstances dire enough that the leader has taken steps to prepare his or her people and the world for the risks of nuclear war that he or she is undertaking.47

Such threats seek to exploit fear of possible nuclear first use for a variety of political and military benefits; they derive much of their power from the accompanying physical preparations and worsening situation of the threat-maker that highlight the means and the motive for a nuclear attack. Much as ‘actions speak louder than words’, military preparations to arm and launch nuclear weapons speak louder than any but the most explicit words of heads of state. (Recall, though, the difficulty of distinguishing whether some military actions are to prepare for conducting a nuclear attack or to protect one’s assets from the adversary’s possible preemptive attack on them.)

Imminence is important because, presumably, the immediate context will matter a lot in a leader’s decision to authorize nuclear attack. He or she may feel differently about the situation today than four months ago and may assess his or her interests one month hence differently than today. As a general principle, the narrower the timeframe and the more specific the demand, the more serious the threat.

Leaders typically speak ambiguously for numerous reasons. ‘All options are on the table’ becomes a default formulation. Yet, it clarifies nothing.

There is no clear legal definition of nuclear threat, so applying the term to a particular set of words and deeds can be controversial.48 That is, some combination of words and deeds would clearly be illegal threats. But leaders typically speak ambiguously for reasons mentioned above and to avoid obvious illegality. ‘All options are on the table’ becomes a default formulation. Yet, it clarifies nothing and in the absence of accompanying preparations and specific invocations of heads of states’ willingness to use nuclear weapons should not be assessed as a nuclear threat.

The Great Rarity of Imminent Nuclear Threats

It is reasonable to say that the term ‘threats’ has been much overused. Former U.S. national security advisor McGeorge Bundy wrote that the United States made no nuclear threats between 1962 and 1984.49 This position is seemingly corroborated by Henry Kissinger in the 1985 Washington Post interview, though several episodes from Kissinger’s time in office with Nixon are frequently cited as nuclear threats. Other scholars, such as Richard Betts, define nuclear threat more loosely as ‘any official suggestion that nuclear weapons may be used if the dispute is not settled on acceptable terms’, and posit that threats were made by the United States to deter and/or compel adversaries in at least five cases, including in 1973 and 1980.50 Betts went on to write that, compared to the United States, Soviet threats were ‘less frequent, restricted to rhetorical allusions, and more often seen only as bluster because the threats were usually issued after the peak of the crisis had passed’.51 This raises the question, why call such manipulations, or allusions, threats?

Acknowledging the rarity of threats of imminent nuclear use, for illustrative purposes here we assess that Russia posed one serious nuclear threat in the current Ukraine war. On 21 September 2022, when Russian forces were being routed in Kharkiv and Kherson, Putin declared: ‘In the event of a threat to the territorial integrity of our country and to defend Russia and our people, we will certainly make use of all weapon systems available to us. This is not a bluff’.52 This statement and the circumstances surrounding it, plus intercepted Russian military communications, prompted the U.S. intelligence community to secretly inform then president Joe Biden that there was up to a 50 percent chance Russia would use nuclear weapons against Ukrainian targets if Russian lines failed dramatically and its control of Crimea was in doubt.53 That is, rather than Russia making 135 nuclear threats since its invasion of Ukraine in 2023, it actually made only one such threat that was not allusory—one that materially changed the risk of nuclear war and did not solely exploit widespread fear of nuclear war. For their part, authoritative leaders of India and Pakistan made no credible nuclear threats of nuclear use in the Kargil War of 1999 and the five subsequent violent crises of 2002, 2008, 2016, 2019, and 2025.54

Relieving Manipulations

Not all forms of nuclear manipulation are threatening or fear-invoking. There can also be relieving manipulations: words or deeds that reduce (or appear) to reduce risk or threat. Discourse on nuclear weapons is often so preoccupied with coercion that it underplays the importance (and difficulty) of reassurance. Yet, this is what leaders often are trying to do: reassure their citizens, allied countries, and sometimes even adversaries, that nuclear war is not going to happen. By encompassing both fear-raising and fear-relieving words and deeds under the rubric of ‘nuclear manipulations’, the aim is to correct overuse and emphasis on ‘threat’, ‘deterrence’, and ‘compellence’ that may exacerbate or at least obscure security dilemmas.55

Relieving manipulations may include allusions or gestures toward conflict resolution, military restraints, arms control, and disarmament. Such manipulations are usually intended to produce positive feelings toward the issuing government(s).56 As with coercive manipulations, leaders often have multiple audiences in mind: specific political factions within adversary states’ populations; the leaderships and populations of states allied with the issuing state; the leaderships and populations of states allied with targeted states; and the influential third-party leaders that could intervene in a dispute via sanctions, and so on.

Discourse on nuclear weapons is often so preoccupied with coercion that it underplays the importance (and difficulty) of reassurance. Yet, this is what leaders often are trying to do.

Sustained implementation of agreements to resolve conflicts, restrain forces, and limit and reduce arms would be the highest form of relief from nuclear fear. Such relief was briefly achieved in U.S.-Soviet relations in the mid-1970s and U.S.-Russian relations in the early 1990s.

For allies to whom a nuclear power extends deterrence, reassurance can be pursued through either or both threatening and fear-relieving manipulations. This duality reflects the two sides of allies’ experience of extended nuclear deterrence: fear of abandonment and fear of entrapment.57 When allies fear being abandoned, an allusion, gesture, or threat suggesting resolve to use nuclear weapons can reassure them that their patron will do all it can to defend them. When allies fear being entrapped in a nuclear war of someone else’s making, allusions or gestures that retract threats and invoke risk reduction or disarmament can be reassuring.

Examples of relieving manipulations include the meeting between then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai and Soviet chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin at the Beijing airport on 11 September 1969 to clear the air from the recent conflict and launch negotiations to disengage the armed forces along the disputed areas of the border.58 (It must be noted, however, that the paranoia and self-absorption of the Cultural Revolution prompted Chinese leaders to fear that the Soviet peace gesture was a ‘smoke shell’ intended to ‘camouflage Moscow’s intention to start a sudden large-scale invasion of China’, in the assessment of a leading Chinese scholar.59)

Many people’s fears about nuclear proliferation and war were relieved at least somewhat by the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1968, and the Incidents at Sea, Anti-Ballistic Missile, and SALT I treaties of 1972.60 In 1991, the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives and the START Treaty, building on the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty that eliminated intermediate-range missiles from Europe, formalized and manifested the effort to relieve the nuclear dangers and fears that were so central to the Cold War. The India-Pakistan agreement of 1988 not to attack each other’s nuclear facilities has been updated annually and upheld without challenge.

More recently, Putin’s long statement on 27 October 2022 denying any need for Russia to use nuclear weapons in the Ukraine war, or Putin’s call to continue following the limitations in the New START Treaty past their February 2026 expiration date could be considered relieving manipulations.61 States may also offer pleasing risk reduction or arms control gestures like Japan’s 2018 commitment to reduce its stockpile of separated plutonium and to conduct further reprocessing only when a credible plan to use the separated plutonium existed.62

The Nuclear Taboo as Hybrid Manipulation

Yet another type of nuclear manipulation that tends not to be included in traditional studies of signalling is when leaders and civil society organizations invoke (manipulate) the norm or taboo against using nuclear weapons to ostracize an aggressor. This taboo takes the fear of nuclear war and, instead of threatening to use these weapons, it threatens to impose non-nuclear consequences on those who would make or carry out threats to initiate nuclear use. Such consequences would include intense political and economic sanction and, more ambiguously, intensified non-nuclear military attack.

The Biden administration and its allies sought to strengthen and apply the nuclear taboo against Russia by not alluding or gesturing toward using nuclear weapons no matter what Russia did. Senior U.S. officials never even resorted to the cliché ‘all options are on the table’. Instead, whenever Putin or lesser Russian officials alluded to Russia’s nuclear arsenal and the harm it could inflict on Ukraine and the nations assisting it militarily, Western officials chided them for acting irresponsibly. Various capitals mobilized the G20 heads of state to declare at their Bali meeting on 16 November 2022, that ‘the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons is inadmissible’.63 Several times during the Ukraine war, Putin and others (including Lukashenko) cited the international condemnation that would follow if Russia used nuclear weapons as reasons why Russia was not making nuclear threats.64

Conclusion

Thankfully, serious intentional threats to use nuclear weapons have been rare. New papers by Moeed Yusuf and Rizwan Zeb, and Rakesh Sood, document the underappreciated decades of restraint by Pakistani and Indian leaders, respectively, in not making nuclear threats. Paired with careful assessments of U.S., Russian, and Chinese leaders’ nuclear manipulations since 1962, it becomes clearer that the interests which have kept all leaders from initiating nuclear war since August 1945 have also restrained them from speaking and acting in ways that would cause their opponent to strike first. Acting and speaking as if you will initiate nuclear use is too dangerous to do unless it appears you have no alternative to prevent your nation from being massively destroyed.

Despite national and global interests in nuclear restraint, some officials make allusions and gestures that are portrayed as threats. Manipulators may seek to end or de-escalate an opponent’s military campaign or cause an alliance or partnership to fracture. They may invoke the awesome power of nuclear weapons to reassure their population that they cannot lose the war that is proving more difficult than anticipated or, conversely, to justify seeking a ceasefire.

The wider and less precise our nuclear discourse is, the more fear nuclear manipulators can elicit, and the less precisely governments and citizenries will know when and how to counter them. If ambiguity is a preferred tactic of nuclear bullies, clarity can be a tool of resistance. The need for more precision and clarity will grow as social media, with its brevity and zeal, becomes a conduit of manipulation. The vocabulary suggested here distinguishing allusions from threats, and gestures from preparations, along with the flow chart, provide one way to improve the quality of public assessments and discussion of nuclear manipulations.

Ultimately, heads of state and leaders of militaries must be willing and able to ask each other direct questions about intentions and thresholds for the use of nuclear weapons, and the consequences they would or should expect will follow. Leaders nearing the apocalyptic verge of detonating nuclear weapons against adversaries that could respond in kind owe their citizens and the world the courage to communicate directly about the alternatives before giving the fateful order to launch.

About the Author

George Perkovich is the Japan Chair for a World Without Nuclear Weapons and a senior fellow in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Nuclear Policy Program.

He is the author of the award-winning history, India’s Nuclear Bomb, and the forthcoming Adelphi book, Nuclear Weapons in the Ukraine War, and has served on numerous international and U.S. panels to address challenges of nuclear deterrence, nonproliferation, and disarmament.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Government of Japan and the Edgerton Foundation—in addition to the Carnegie Corporation of New York—for enabling the research and writing of this paper, Sharon Weiner for her astute guidance, and the following individuals for their invaluable critiques and constructive suggestions: Cara Wilson, John Warden, Pranay Vaddi, Todd Sechser, Austin Long, Helena Jordheim, Peter Hayes, Matt Fuhrmann, Paul Davis, and James Acton. For the graphics and editorial guidance, thanks to Jocelyn Soly, Amanda Branom, and Alana Brase. For orchestrating the project, thanks to Steve Freedkin, Nautilus Institute.

The Nautilus Institute, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network thank the Carnegie Corporation of New York for its support of this project and its ongoing support of public-interest work to prevent nuclear conflict.

The Assessing Nuclear ‘Threats’ Project

Russia’s war in Ukraine and five India-Pakistan crises or conflicts suggest that nuclear signaling in the 21st century may be different than during the Cold War. Terms like ‘nuclear threat’ need to be defined with more care and nuance to enable decisionmakers to distinguish serious nuclear threats that demand a countervailing action from nuclear threats that are mere noise or allusion aiming to manipulate nuclear anxiety but do not pose a serious threat of nuclear attack. With the support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Nautilus Institute and the Carnegie Endowment Nuclear Policy Program have produced four major papers and a forthcoming Adelphi book to enhance responses to attempts to manipulate fear of nuclear war in today’s environment. With the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network, they are conducting three YouTube events to foster global discussion.

About the Author

Japan Chair for a World Without Nuclear Weapons, Senior Fellow

George Perkovich is the Japan Chair for a World Without Nuclear Weapons and a senior fellow in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Nuclear Policy Program. He works primarily on nuclear deterrence, nonproliferation, and disarmament issues, and is leading a study on nuclear signaling in the 21st century.

- “A House of Dynamite” Shows Why No Leader Should Have a Nuclear TriggerCommentary

- Rethinking a Political Approach to Nuclear AbolitionReport

George Perkovich, Fumihiko Yoshida, Michiru Nishida

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Duqm at the Crossroads: Oman’s Strategic Port and Its Role in Vision 2040Commentary

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- Beijing Doesn’t Think Like Washington—and the Iran Conflict Shows WhyCommentary

Arguing that Chinese policy is hung on alliances—with imputations of obligation—misses the point.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- How Far Can Russian Arms Help Iran?Commentary

Arms supplies from Russia to Iran will not only continue, but could grow significantly if Russia gets the opportunity.

Nikita Smagin