Alexey Malashenko

{

"authors": [

"Alexey Malashenko"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Caucasus",

"Russia",

"Azerbaijan",

"Armenia"

],

"topics": [

"Security",

"Military",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

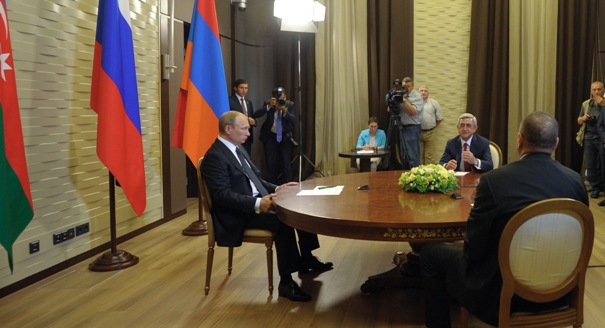

Source: Getty

Putin Brings Armenian and Azeri Leaders Together, But No Solution to Karabakh in Sight

The Sochi meeting between Russia’s, Armenia’s, and Azerbaijan’s presidents is but one episode in the series of Russia’s protracted peacemaking efforts. Rather, the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict serves as a great pretext for Russia’s presence in the South Caucasus.

It is unlikely that the August 10 Sochi meeting between Russia’s, Armenia’s, and Azerbaijan’s presidents will become a turning point in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This is but one episode in the series of Russia’s protracted peacemaking efforts. Rather, the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict serves as a great pretext for Russia’s presence in the South Caucasus. As long as the conflict continues, and no one knows how long it will last, Russia will maintain its presence in the region. If the conflict is somehow miraculously resolved, Moscow’s sway over both Azerbaijan and Armenia will diminish.

However, in Nagorno-Karabakh, we are dealing with a perennial conflict, which will remain fundamentally unchanged unless some global political upheavals are to occur.

So how is this trilateral summit different from other meetings of similar format?

Second, the success of Russia’s peacemaking efforts would be quite useful to Moscow at this time. The Ukrainian crisis devalues Russia’s peacemaking efforts; fewer and fewer people still believe it is willing and able to resolve conflicts in the post-Soviet space. Interestingly enough, the smiling Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan asked Putin to keep him informed of the steps Russia takes in Ukraine, promising to do the same vis-à-vis the events in the Caucasus region.

In other words, if Russia is able to succeed in its peacemaking efforts now, it might somewhat restore its dented international reputation.

Third, Russia is seeking to strengthen its position in the post-Soviet space more than ever before. In this context, it is interested in maintaining good working relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan. It is especially true in light of the fact that Armenia is Russia’s strategic partner; it is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization and also intends to join the Customs Union and possibly the Eurasian Union. For its part, Azerbaijan, which has always considered Russia one of its major international partners, will have to overcome the temptation to supply Europe with gas under the so-called Southern Gas Corridor initiative, thus taking Russia out of the energy equation. So it is getting increasingly more difficult for Russia to preserve balance in its relations with both countries.

Fourth, it is possible that Russia may take some unconventional steps to validate its status of a peacemaker. For instance, it may offer to send its peacekeepers into the region (such rumors had been circulating before the start of the summit). Such an event seems unlikely, but if it indeed takes place, it may create a precedent for more Russian peacekeeping engagements in some other regions, such as the southeast of Ukraine.

In any event, the August trilateral summit goes beyond the actual Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, while the conflict itself remains unresolved.

About the Author

Former Scholar in Residence, Religion, Society, and Security Program

Malashenko is a former chair of the Carnegie Moscow Center’s Religion, Society, and Security Program.

- What Will Uzbekistan’s New President Do?Commentary

- Preserving the Calm in Russia’s Muslim CommunityCommentary

Alexey Malashenko

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

Putin is stalling, waiting for a breakthrough on the front lines or a grand bargain in which Trump will give him something more than Ukraine in exchange for concessions on Ukraine. And if that doesn’t happen, the conflict could be expanded beyond Ukraine.

Alexander Baunov

- Russia in Africa: Examining Moscow’s Influence and Its LimitsResearch

As Moscow looks for opportunities to build inroads on the continent, governments in West and Southern Africa are identifying new ways to promote their goals—and facing new risks.

- +1

Nate Reynolds, ed., Frances Z. Brown, ed., Frederic Wehrey, ed., …

- Trump’s State of the Union Was as Light on Foreign Policy as He Is on StrategyCommentary

The speech addressed Iran but said little about Ukraine, China, Gaza, or other global sources of tension.

Aaron David Miller