Paul Haenle, Philippe Le Corre

{

"authors": [

"Philippe Le Corre"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "asia",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "AP",

"programs": [

"Asia",

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"East Asia",

"China",

"Eastern Europe",

"Western Europe",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Trade"

]

}

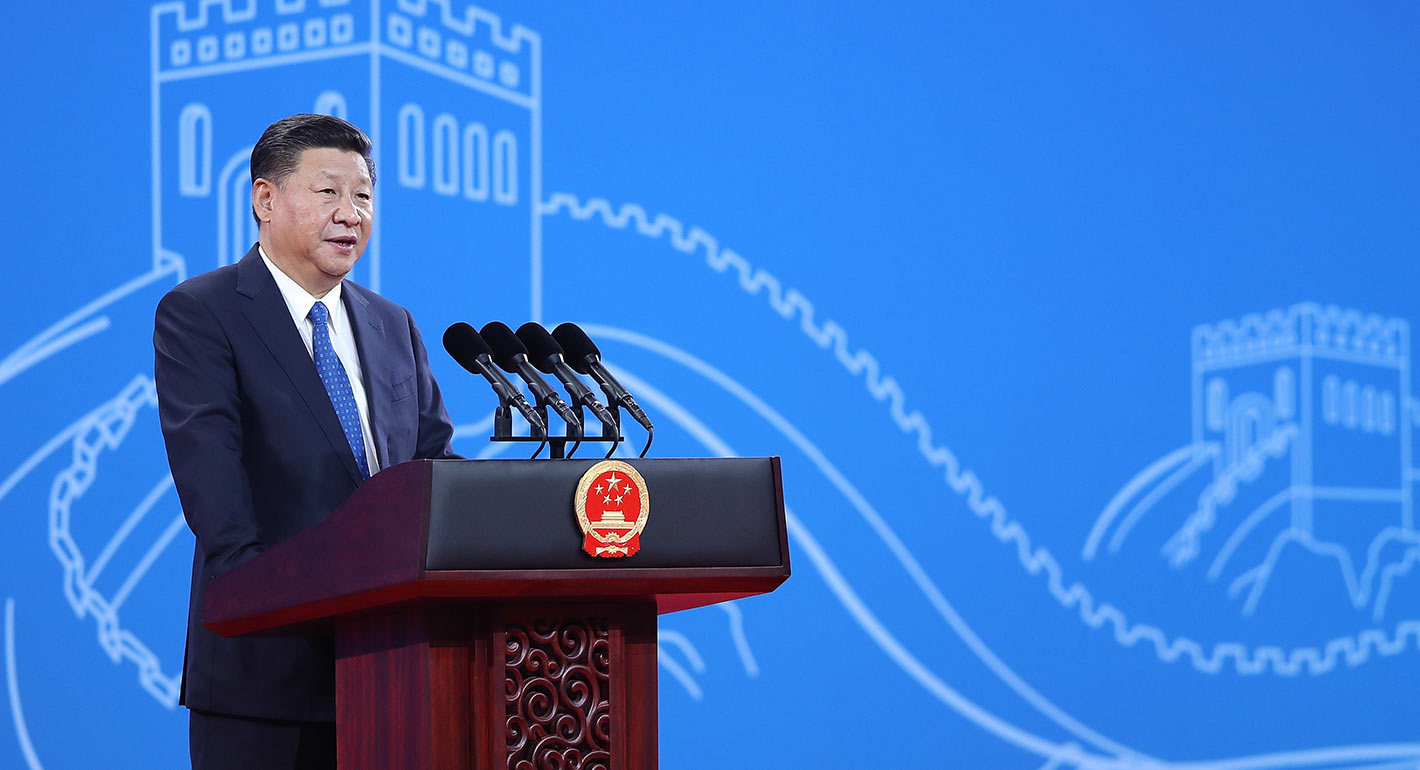

Source: Getty

This is China’s Plan to Dominate Southern Europe

Chinese state-owned companies are using their financial leverage to build strongholds in Portugal, Greece and Italy. Many of the targeted countries are becoming soft supporters of China on the international stage.

Source: National Interest

China’s deep pockets and generous investments are turning to Southern Europe—the latest target in its influence campaign to establish Chinese business, cultural, and diplomatic presence around the world. Chinese state-owned companies are using their financial leverage to build strongholds in Portugal, Greece and Italy.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, China has become a significant creditor to many severely indebted European Union nations. Portugal, Greece, and Italy were all forced to privatize some of their state assets following the euro-debt crisis, making their economies partly dependent on Chinese investors. Private acquisitions also multiplied.

China’s investment strategy in Southern Europe has involved significant purchases of large European firms. When Portugal started privatizing some of its utilities, China Three Gorges Corporation (CTG), a Chinese state-owned power company, became a shareholder of Energias de Portugal SA (EDP), the country’s formerly state-owned grid company. CTG is now bidding for a majority share of EDP’s capital. Other Chinese investments in energy include Redes Energéticas Nacionais and Galp Energia. Additionally, China has bought stakes in Portugal’s national carrier Transportes Aéreos Portugueses, insurer Fidelidade, hospitals, real estate and even media. KNG, a Macau-based Chinese fund, acquired 30 percent of Global Media Group, the owner of the Portuguese newspapers Diário de Notícias and Jornal de Notícias , and Radio TSF.

China’s influence campaign isn’t limited only to Portugal. In Greece, shipping giant China Overseas Shipping Group Company (COSCO) was granted a license to run no less than 67 percent of Greece’s largest seaport, Athens’ Piraeus harbor—establishing a Mediterranean hub for Chinese companies and challenging Greek shipowners. Furthermore, other examples include China State Grid, a Chinese-state owned utility company, which has invested in IPTO, a major Greek transmission operator.

Next door in Italy, Chinese investors also bought brands such as tire manufacturer Pirelli or machine-tools maker Cifa. Chinese funds invested in strategic Italian energy entities such as Eni, Enel or the Italian national electricity agency CDP Reti (China State Grid acquired 35 percent of its capital). Moreover, Chinese investors purchased shares in Fiat Chrysler (automobiles), Ferretti (yachts), Telecom Italia, and world-famous fashion designer Ferragamo. Chinese investors have also bought hundreds of Italian small and medium businesses.

Do these economic activities translate into political influence for China in these countries?

Since these investments, many of the targeted countries are becoming soft supporters of China on the international stage. In June 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement at the United Nations criticizing China’s human rights record. EU diplomats said this vote undermined efforts to confront Beijing’s crackdown on activists and dissidents. A year ago, when the European Commission, backed by Germany and France, called for a more cautious approach towards foreign investment in infrastructure or technology, several countries—including Greece—said they would not support the move.

Meanwhile, Italy unexpectedly appointed a former Shanghai-based finance professor, Michele Geraci, as the country’s undersecretary for economic development. Geraci has long been a supporter of Chinese investment and has been suggesting in press statements that Italy could become “China’s friend in the Mediterranean.” Among other ideas, he wants to work with China on its payments technology including through Tencent’s WeChat service, and on joint ventures in Africa.

There is little doubt that China has been using its economic role to build support for its international goals. Alongside the EU, Beijing has created a network of friendly countries—sometimes through formal mechanisms, such as the 16+1 forum (where China meets annually sixteen Eastern and Central European nations); sometimes through informal, bilateral processes, especially in Southern Europe (where attempts to create a 5+1 forum have not materialized).

In Greece and Portugal, two former European empires with limited historical relations with China (outside of colonialism), Beijing has become an important player. It has started building an image as a cash-rich power that can provide financial help and support at a time when Western powers are supposedly “withdrawing.” While the EU has continued to put forward its principles including human rights, Greece and Portugal have become cautious in criticizing China on the world stage on issues of human rights or diplomacy to avoid damaging prosperous economic relations. In Portugal, in particular, there has been little public debate about China’s rising economic impact. Moreover, relations between Portugal and China seem on track to deepen ahead of Xi Jinping’s state visit in December. During the same trip, Xi will also visit neighboring Spain. The Portuguese government has declared itself open to a discussion about leasing Portugal’s large Sines Port to a Chinese operator. The port is “Located at the juncture between the Mediterranean Sea and northern Europe” and “can and will provide for the intersection between the land and maritime routes of the Belt and Road Initiative, whose potential is unquestionable,” according to Portuguese foreign minister Augusto Santos Silva.

There is a strong possibility that Southern Europe might become a zone of strong Chinese influence in the future. In an economically weakened region with rising anti-European sentiment, citizens might be looking at alternative options. For example, According to the Pew Research 2018 global survey , Italian and Greek public opinions are becoming more positive towards China compared to previous years.

But Southern European countries are democracies and EU members. Although their economic needs are understandable, they should stick to European rules and principles to remain full members of the Union. Instead of splitting the EU, they should rally behind European values and remain cautious about welcoming foreign investments in sensitive areas such as energy, technology and infrastructure. For its part, Brussels should offer alternatives, stick to its plan of reinforcing consultations at EU-level on strategic investments and strengthen coordination—especially with Southern Europe.

This article was originally published in the National Interest.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Senior Fellow, Europe Program

Philippe Le Corre was a nonresident senior fellow in the Europe Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Has Jeopardized the China-EU RelationshipQ&A

- China’s Influence in Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four CountriesPaper

- +1

Erik Brattberg, Philippe Le Corre, Paul Stronski, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- How Far Can Russian Arms Help Iran?Commentary

Arms supplies from Russia to Iran will not only continue, but could grow significantly if Russia gets the opportunity.

Nikita Smagin

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- China Is Worried About AI Companions. Here’s What It’s Doing About Them.Article

A new draft regulation on “anthropomorphic AI” could impose significant new compliance burdens on the makers of AI companions and chatbots.

Scott Singer, Matt Sheehan

- Trump’s State of the Union Was as Light on Foreign Policy as He Is on StrategyCommentary

The speech addressed Iran but said little about Ukraine, China, Gaza, or other global sources of tension.

Aaron David Miller